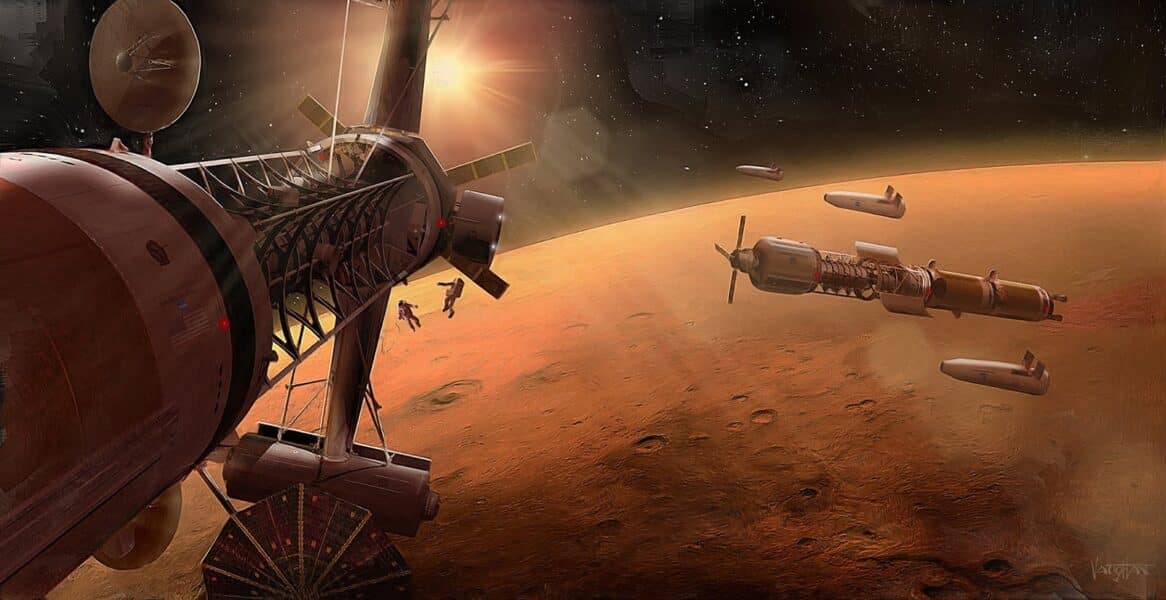

Who has never dreamed of looking over the surface of Mars from the top of Olympus Mons, the highest mountain in the Solar System? Who wouldn’t want to admire the blue sunsets on the Red Planet at least once in their lifetime?

If the journey between Earth and Mars is sometimes no more than a page-turner in a science fiction novel, it is a different story in real life. Complex, dangerous, utopian, suicidal… there is no shortage of adverts from private companies promising the first man (or woman) on Mars by the end of the decade.

What are the obstacles to the exploration (dare we say, colonisation) of Mars? Why aren’t we already reserving our living space near the slopes of Valles Marineris? Let’s take a look…

“It’s not the destination that’s important, it’s the journey” they used to say…

Unfortunately, the problems will not start once we arrive on Mars, but long before. At present, humans have never gone further than the lunar orbit, 3 or 4 days away from our planet. And even in these cases, if there is the slightest problem on board, or if no more commands respond, the immutable laws of space mechanics always manage to bring the ship back to Earth by itself. This is what happened on 14 April 1970 when a liquid oxygen tank exploded in the Apollo 13 service module, ending the mission. After three days of survival in a ripped open spacecraft, the astronauts were able to return safely to Earth.

Unfortunately, a scenario like this is unthinkable during a transfer between Mars and Earth. This journey would last between 6 and 9 months, during which time the spacecraft would become a truly autonomous world, capable of providing water, oxygen and food to a crew subjected to an environment far more hostile than anything ever simulated or experienced.

Protecting, feeding, watering

In addition to communications, which will become longer as the distance between the spacecraft and the control centre increases, eventually reaching more than 10 minutes between the transmission and reception of a message, one of the main problems concerns cosmic rays, the flow of energetic particles (protons, electrons, heavy atomic nuclei) that bathe interplanetary space, irradiating all objects in it. Although there are space environments that today allow humans to train for long stays in space, such as the International Space Station (ISS), the situation is not the same. The ISS rotates at an altitude of 400 km, and in these conditions it benefits greatly from the protective shielding effect of the Earth’s magnetic field (the magnetosphere), which slows down and deflects a fraction of cosmic rays.

And radiation protection is just one of the many problems that will have to be solved before sending humans to Mars. As for water, a lot of work has been done on the ISS and there is now a very efficient system that recycles urine and even recovers the water vapour emitted by breathing and perspiration to filter it and make drinking water. But even so, losses are inevitable, and the cargo ships that leave for the ISS every month always bring some water for refuelling.

As far as food is concerned, the problem is far from being solved. It is impossible, for example, to carry 12 to 18 months’ worth of provisions in a trailer behind the spacecraft (assuming that the crew is not abandoned without the possibility of returning, in which case the amount to be carried can be halved).

However, there is still some research to find solutions on the ISS. Since 2019, the BioNutrients‑1 (then 2) experiment has been studying the functioning of certain yeasts and bacteria that have been genetically modified to produce antioxidants, vitamin A or proteins to maintain the astronauts’ muscle mass. With the progress of gene editing, it is not unrealistic to imagine, in the long term, micro-organisms capable, for example, of breaking down human faeces into simple molecules, and others programmed to use this elementary soup to produce proteins, fats, fibres and other consumable carbohydrates – and to be able to recycle, this time, some of the human solid matter.

What are the effects on the human body?

Another well-known problem of the space environment on the human body is the decalcification of bones. This phenomenon can be slowed down by a suitable diet and daily exercise, but this loss is inevitable (1% of bone mass lost per month). Here again, a solution could come from biotechnology. The idea is to use the vegetables produced inside the vessel in the most efficient and versatile way possible. In addition to producing a little oxygen by consuming CO2 and serving as human food, it is also envisaged that they could be used as a… pharmacy.

In space, astronauts lose 1% of their bone mass per month.

In 2022, a University of California study was published on the growth in space of a genetically modified lettuce that produces some human parathyroid hormone, which, among other things, helps stimulate bone growth. Daily consumption of this lettuce could eventually help astronauts maintain their bone density during long space travel. We can then imagine having a programmable plant pharmacopoeia inside the spacecraft, edited as needed, without having to take a whole pharmacy with us on take-off.

Finally, the human factor is also a very sensitive parameter that does not necessarily guarantee the success of a hypothetical mission to Mars. A lot of research is currently being carried out on the ability of a small group of pseudo-astronauts to remain alone, living in promiscuity 24 hours a day without the possibility of changing anything. But these studies also have their limits because they take place in environments that are certainly isolated, but which remain on Earth. The knowledge that there is no way back and that all of humanity is behind you is impossible to simulate.

Few scientists doubt that Mars is forever out of reach. But that doesn’t make the trip ready for tomorrow. Although intensive work is currently being done to prepare mankind for the first interplanetary journeys, the current state of knowledge and technology for making this journey certainly does not make it possible to envisage it for the near future.