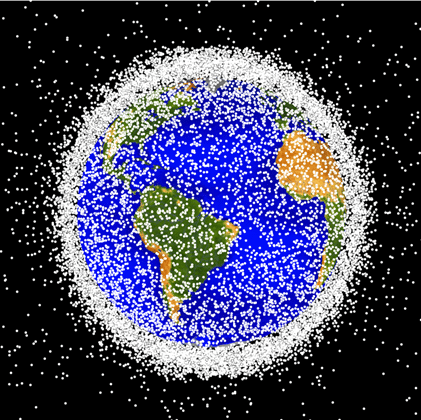

The proliferation of space debris in the Earth’s orbit

- Today, there are 36,000 objects larger than 10 cm in space, of which 30,000 are catalogued and 6,000 are not referenced.

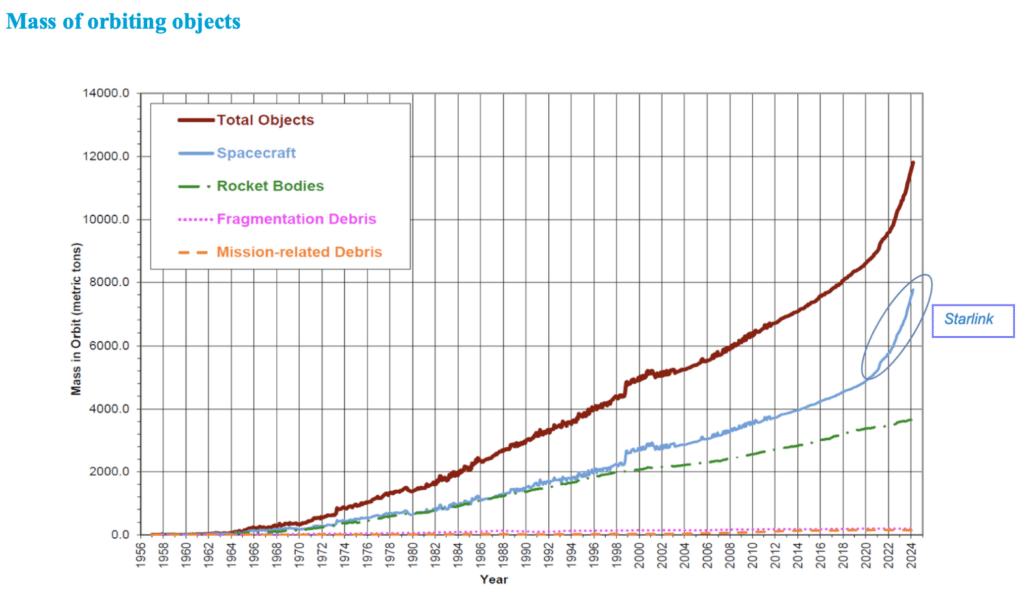

- The mass of objects in orbit in space is 13,486 tonnes, which is a little more than the weight of the Eiffel Tower.

- In the most congested area, the amount of debris generated by collisions is greater than the amount that is naturally destroyed by falling back into the atmosphere.

- Observation satellites were often sent to the 80 km orbit zone, and they can still be sent there, but the chance of destruction is around 10%

- The quantity of space debris could double in less than 50 years, so ten large pieces of debris must be removed every year before they fragment, and international regulations must be respected.

In 2021, there were 24,000 objects in orbit larger than 10 cm in space. What is the situation today?

Christophe Bonnal. There is now an additional 12,000 objects. Today, there are 36,000 objects larger than 10 cm, 30,000 of which are well documented. These are so-called “catalogued” objects, identified by a name or number, whose trajectory is known. The remaining 6,000 are unreferenced military objects, or objects that are difficult to track continuously.

Be warned, these “space objects” may be pieces of dead satellites or what are known as “operational debris” such as straps, covers, etc. As an operator is not required to declare whether or not their satellite is live, it is difficult to distinguish functional objects from space debris, but we do have some estimates. For example, we know there are 10,500 active satellites in orbit.

When does a “space object” become debris?

It’s hard to say. The definition of debris is “a non-functional space object of human origin (…).” But what is “non-functional”? When Peter Beck, from the Californian start-up Rocket Lab, sent a giant mirror ball one metre in diameter into space, the scientific community denounced the uselessness of the project. His response? The disco ball was an advertising feature, so could not be categorised as debris… Beyond this anecdote, the debate rages on, particularly with the countries that pollute the most. Today, 96% of orbital debris is the responsibility of the United States, Russia and China, with each country accounting for a third.

Space objects eventually fall back into the atmosphere naturally: isn’t that enough to reduce space congestion?

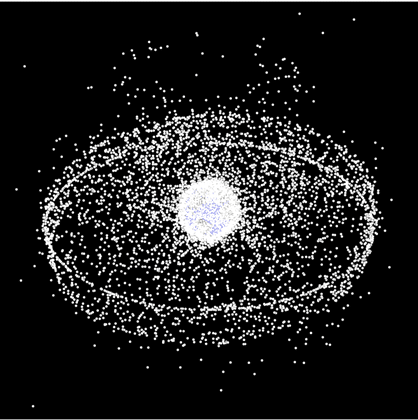

In 2023, there were 2,800 entries into orbit and 2,000 exits. These de-orbiting operations are carried out in two ways: active withdrawal, particularly when there are humans in a capsule; and natural de-orbiting linked to the dynamic pressure of the atmosphere. The higher the object, the slower it descends: ten years for a satellite at an altitude of 400 km, two centuries for those at 800 km and a thousand years for objects at 1,000 km.

Furthermore, the mass of objects in orbit is 13,486 tonnes, which is a little more than the weight of the Eiffel Tower, which is 10,000 tonnes. The conventional estimate is around 4,000 tonnes of useless rocket stages and approximately 8,000 tonnes of satellites, half of which are thought to be non-functional. The most congested area is in low orbit between 750 and 1,000 km. These are known as LEO (low Earth orbit) objects. In this area, the generation of debris by collision is greater than the natural destruction by atmospheric re-entry. This causes a chain reaction known as the Kessler syndrome.

Are there any orbits where Kessler syndrome is too prevalent and rules out the possibility of launching satellites there?

Not really, but the 800 km orbit was the preferred option for observation satellites. At this altitude, there are a thousand times more pieces of debris than active satellites. This “rotten”, highly polluted zone is not prohibited, and satellites can still be sent there, but their probability of premature destruction by collision is now 10%. But the situation is worsening.

In its latest report from January 20251, the IADC (Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee), the agency that brings together the world’s thirteen major space agencies2, concludes that “the amount of space debris could double in less than 50 years.” It has also published a unanimously approved note, which could be summarised as follows: “Mitigation will not be enough. We need remediation.” In other words, beyond the natural decrease in space objects, we must implement space rehabilitation techniques.

In 2021, you talked to us about lasers in particular: is this still relevant?

It is a valid technique that can be used to remove small debris, for example, but there are a million 1cm pieces of debris, so we’re not finished yet! What’s more, these are large lasers that are considered to be weapons.

To stabilise the environment, ten large pieces of debris would have to be removed each year before they fragment, while scrupulously respecting current international regulations. The list of the 50 largest pieces of debris to be retrieved as a priority was published in 20213. The solution would therefore be a hunter with a robotic arm or a net to capture the debris and bring it down to de-orbit it in the Pacific. But there is a real obstacle: if we are technically capable of removing our own debris, we would then be acting on foreign space objects and there is a real notion of space war. Hence, the profound lack of enthusiasm of funding bodies. Especially since the current estimates for a robotic garbage collector in orbit are around 20 million euros, several times the price of a new space object!

One question that emerges is that of the pollution caused by de-orbiting in the upper layers of the atmosphere. What do we know today about the effect of this disintegration?

This is one of the subjects I am working on, Design for non-Demise, or how to build space objects that do not melt at all on entry into the atmosphere. Today, only 20% of the mass of a deorbited object ends up on the surface of the globe, mainly because of materials such as titanium, stainless steel or carbon. This leaves the problem of the remaining 80% of the mass that has burned up in the atmosphere, releasing aerosols such as alumina [Editor’s note: aluminium oxide] or soot, which directly affect the ozone layer. In reality, the consequences of these emissions are still unknown. With the arrival of satellite constellations such as Starlink and the proliferation of space operations, this pollution will unfortunately increase exponentially.

Interview by Sophie Podevin

Find out more:

- American website for the general public that allows users to follow catalogued space objects in real time: https://www.space-track.org

- Article on the 50 biggest pieces of space debris in low orbit to be retrieved as a priority: https://cnes.fr/actualites/top-50-debris-spatiaux-plus-dangereux (2021)

- First official IADC reference guide on debris mitigation (2007): https://www.unoosa.org/documents/pdf/spacelaw/sd/IADC-2002–01-IADC-Space_Debris-Guidelines-Revision1.pdf

- Resource site of astrophysicist Jonathan McDowell, which archives data on all space objects: https://planet4589.org/index.html

- Scientific study published in June 2024 on the pollution caused by satellite de-orbiting on the ozone layer: https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2024GL109280