With the advent of the digital age, protest movements are now being expressed and organised differently. In the past, they were, for example, led by trade unions or political parties that struggled to establish demonstrations with a high level of mobilisation, due to a lack of coordination. And if they did manage to mobilise people, it had to be through intermediaries due to these coordination problems.

Today, with social networks, things are different: it is much simpler to pick up on protest signals and to organise, making it easier to build movements around these aggregates of anger. Germain Gauthier, a doctoral student in economics, works on the impact of social networks on the formation of this type of movement. He analyses two recent protest movements: the “Me Too” movement and the “Yellow Vests” protests in France.

The Yellow Vests and Facebook

The Yellow Vests – a sporadic movement born out of the protest around the rise in fuel prices in France which began in 2018 – is one of the typical examples of the new protests and the digital organisation that has sprung up around them. No leader, no political parties, just a population at the end of its tether in a highly complex economic situation, mobilising en masse via social networks12. This movement gave rise to demands that went beyond the price of petrol and extended to the re-establishment of the wealth tax, while remaining somewhat confused due to the lack of structure of the movement.

Indeed, the creation of numerous groups on Facebook, still active today, is one of the organisational elements of the movement. To better understand it, Germain Gauthier and his co-authors mapped the online and offline mobilisations of the Yellow Vests. For online mobilisation, they listed more than 3,000 geolocated groups on Facebook with nearly 4 million members in total; as well as millions of messages posted on hundreds of pages related to the Yellow Vests. For offline mobilisation, the researchers have a map of intentions to demonstrate on the evening of the first rally, on 17th November 2018, which brings together nearly 300,000 protesters.

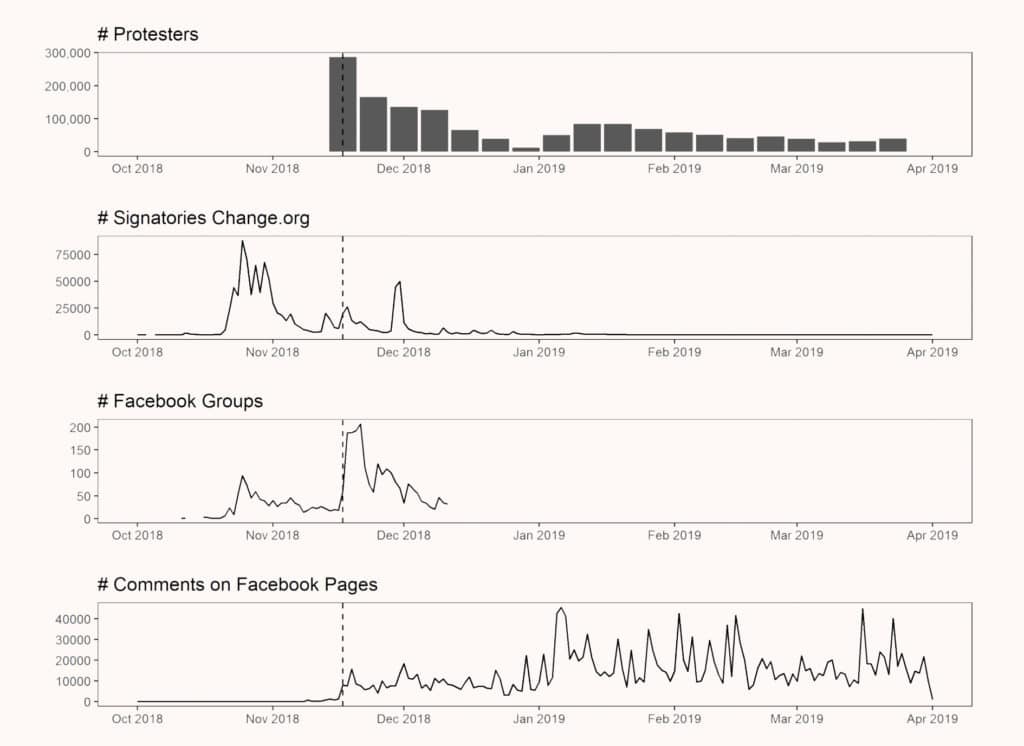

The correlation between attendance in Facebook groups and the general mobilisation of the Yellow Vests movement is very real. Moreover, unlike movements that could not benefit from the impetus of social networks, offline mobilisation persists even after the massive mobilisation in the streets (see graph below).

This graph shows the relationship between offline and online mobilisation, but also the movement’s ability to endure over time. It can be seen that the curve relating to comments on Facebook pages only decreases slightly, unlike the mobilisation.

Germain Gauthier explains, “the spatial correlation between Facebook groups and organised physical blockades is largely positive and explains the offline mobilisation more than the administrative socio-demographic data of the regions. On the eve of 17th November, there were nearly 918 Facebook groups with more than 100 members – that’s already more than a million potential protesters. If this first online mobilisation was impressive, the second was even more so. In the aftermath of 17th November, a new wave of Facebook groups was created, feeding the movement and keeping the protest alive on social networks4.”

This study therefore shows that the Yellow Vests movement has tended to multiply in an innovative digital era, defying codes and mobilising a large number of people. The question which remains unanswered is that of prediction. Will it be possible, in the near future, to predict protest movements by simply analysing “big data”?

Germain Gauthier does not think so, but he warns, “our ability to predict the appearance of social movements is still poor. However, many dictatorial regimes around the world have understood the importance of social networks (and more generally of digital traces) for monitoring populations. From that point of view, the risk is very real.”

Me Too, a new generation of protest

Germain Gauthier also studied a different type of protest movement in the MeToo phenomenon, which encourages women to speak out and express themselves, from social networks, on sexual violence. This movement gained momentum at the time of the Weinstein affair in 2017.

Whilst Me Too does not create large demonstrations in the streets, it offers an unprecedented level of mobilisation on social networks while impacting real life through free speech and disrupting social codes. Gauthier compares the MeToo movement to May 68 (in France), explaining that, “this movement is already shaking up societal codes oppressing women and aims to profoundly change societal norms in the long term.” The pressure of the movement is then applied to many institutions. As such, the mobilisation on social networks means that, even without large protests in the real world like the Yellow Vest, the global movement that is MeToo is forcing politicians to look at social networks and become aware of their impact.

Gauthier provides an accurate measure of this impact by using a number of variables to highlight the potential correlation between the MeToo movement on social networks and sex crime complaints. By comparing sex crime complaints before and after the appearance of the “#Metoo” hashtag, which went viral on Twitter in October 2017, he observes a significant increase in sex crime complaints in the United States (around +20% between 2017 and 2018 for New York City, for example).

But the MeToo movement seems to be the culmination of an anger that has been resonating for years on social networks. Since 2010, the number of references to sexual violence on social networks has been steadily increasing. In his report on the subject, he writes, “empirical findings indicate substantial pre-trends before the advent of the MeToo movement. I estimate that the share of victims who eventually report a sex crime to the police doubled between 2009 and 2017, from 30% to 60%. In terms of the incidence of sex crimes, my estimates suggest a 50% decrease in New York City and a 20% decrease in Los Angeles. »

There are several notable examples to show the economic impact of the movement: the 16% drop in the Wynn Resort Group after accusations of sexual harassment against the CEO, the 21% drop in the Guess Group, again for the same reasons. Not to mention the bankruptcy of the studio founded by Harvey Weinstein.

All of these examples show us that even without significant offline mobilisation, online mobilisation can have many impacts on companies and policies. Social networks are now at the heart of society and the line between online and offline has never been so blurred.

“We still can’t predict the next big moves in social networks. But, thanks to the data we can get from them, we are able to look very closely at how movements develop,” he concludes. “Nevertheless, it is difficult to know today whether the way movements are progressing is due to social networks or not. For example, if we had access to this kind of data during the Margaret Thatcher era in the UK, we might see the same patterns…”