Three keys to making good decisions

The World Health Organisation (WHO) recently listed knowing how to make decisions as one of the ten psychosocial skills required to respond effectively to the demands and challenges of modern daily life. Classically, neuroscience distinguishes three stages in decision making1 : definition of preferences, execution and observation of an action and finally experience of the result. Here, I offer some of the pitfalls within each of these stages and offer suggestions of how to overcome them by looking at three major psychological duels.

Duel #1 : heuristic vs. systematic

“Am making the right decision?”

The process of ‘deciding’ consists of managing the conflict that occurs between the two speeds at which our thoughts occur. ‘System 1’ is rapid, low effort, intuitive and heuristic, compared to system 2 that is slow, systematic, logical, and deliberate2. Both have their advantages (speed, ease, reliability, relevance) and disadvantages (bias, noise, cost, fatigue), which are the source of much scientific debate. Nonetheless, the key to managing this duel is found in process of inhibition3 ; in other words, succeeding (when necessary) in suspending hasty judgement, ready-made routines, consensual stereotypes and cognitive biases – in other words, knowing when not to act.

Of course, it is more difficult to inhibit routines than it is follow pre-learned patterns because it requires new information to be learned and practised. As such, applying strict selectivity to a decision consists of measuring and weighing up the duel between the two speeds of the mind that drive our choices45, knowing that sometimes intuitive decisions may, in fact, prove to be more effective6.

Application #1

Here is an example of a decision you could come across : “Play the lottery in such a way as to win the most money”. Take a minute to place five numbers on a grid from 1 to 49 and think about the duel that is going on inside you – probably unconsciously. Generally, we mobilise system 1 to play the lottery. For example, using the availability of ‘lucky’ numbers (such as birthdays) or the representation bias of chance which leads us to spread out our numbers, to “increase our chances”7 ! However, as it turns out, everyone tends to use the same methods and biases. So, when we observe the grids of lotto players, we notice on the one hand that there is a saturation of choices between 1 and 31 (dates of birth) and on the other hand that there are very few sequences. To respect the initial task (optimise winnings) you must do what the others don’t do. That means you should play numbers above 31, and include sequences, because few other people do so. Thus, in the event of a successful draw you don’t have to share the winning ! As we can see in this example, “playing well” consists of inhibiting the natural drive towards our superstitions and biases therefore trying to fight against oneself. This is true in most of our daily decision-making.

Duel #2 : perseverance vs. persistence

“Did I do the right thing?”

The greater the investment in time, energy, or resources (human, financial, etc.), the stronger the will to legitimise the decision taken. But how far can we persevere to the point of no longer being objective, no longer seeing the facts or hearing the arguments that clearly call into question the decision we made ? While it is good and socially valued to be persistent, it is important to identify the almost obsessive pursuit of an action against all objective reason89.

Once the decision has been made, the implacable logic of ‘sunk costs’ sets in, with its share of well-known cognitive biases that are hard to shake off : hypothesis confirmation (I look for arguments that confirm my decision and only those arguments), status quo (if there is no reason to change, then why change ?), loss aversion (to risk losing because of a change is psychologically unbearable).

It is difficult to fight against this dilemma alone since we are often only dimly aware of our own cognitive biases. Hence, taking countermeasures can make it possible to avoid these traps beforehand. For example, ensuring that the people who make decisions are not the same as those who evaluate the effects and therefore the continuation of the decision taken. This is why, for example, new presidents who come to power can more easily stop processes that were started 20 years ago and which everyone knew were ineffective…

Application #2

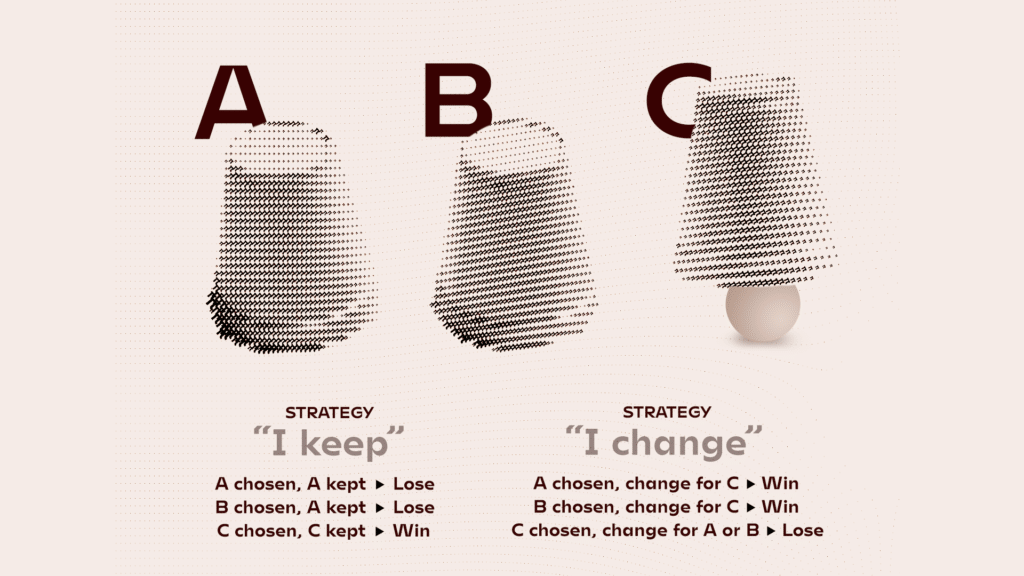

the Monty Hall dilemma10 illustrates this decision-making trap well. Imagine you have three opaque cups A, B and C in front of you. Under one of them you have hidden, for example, a €50 note, under the other two nothing. You must choose a cup with the objective of winning the €50. For example, you choose A. The host then turns over one of the two remaining cups that he is sure does not contain the €50 – B, for example. You are then offered another choice : keep the original choice (A) or take the remaining one (C). What do you do ? The overwhelming majority of participants decide to stay with the initial choice (A), believing that there is no reason to change. However, to maximise the gain, it is necessary to change because the remaining cup (C) has the same probability as the returned cup (B). It is remarkable to carry out this experiment in a group and to note on the one hand to what extent the arguments of the participants reflect the above-mentioned cognitive biases, and on the other hand to what extent the divergent minority positions (changing the cup) are obscured from the debate by the majority who fiercely maintain that changing is irrelevant.

Duel #3 : investigator or lawyer ?

“Was I right?”

Our minds are particularly adept at reconstructing past sequences by attributing internal causes (skill, effort) to our successes and external causes (difficulty, environment) to our failures. Hindsight bias is the enemy of reliable debriefing and feedback, since once the effects of a decision are known, its function is to give us the feeling that we always knew beforehand what was going to happen. It acts as a control of uncertainty : “it was obvious, I knew it would work”. In a way, one becomes a lawyer who seeks to exonerate or incriminate those accused of a bad decision, which results in a search for those guilty and responsible who “knew but said nothing”. The current health crisis shows that the witch-hunt can rapidly take hold. To avoid this trap, both for oneself and for others, it is important to record the maximum amount of information available at the time decisions are made. This enables us to carry out a real investigation afterwards, with the aim of improving our future decision-making and to avoid the lawyer in us constructing a “fake news fiction” storyline, after the fact11.