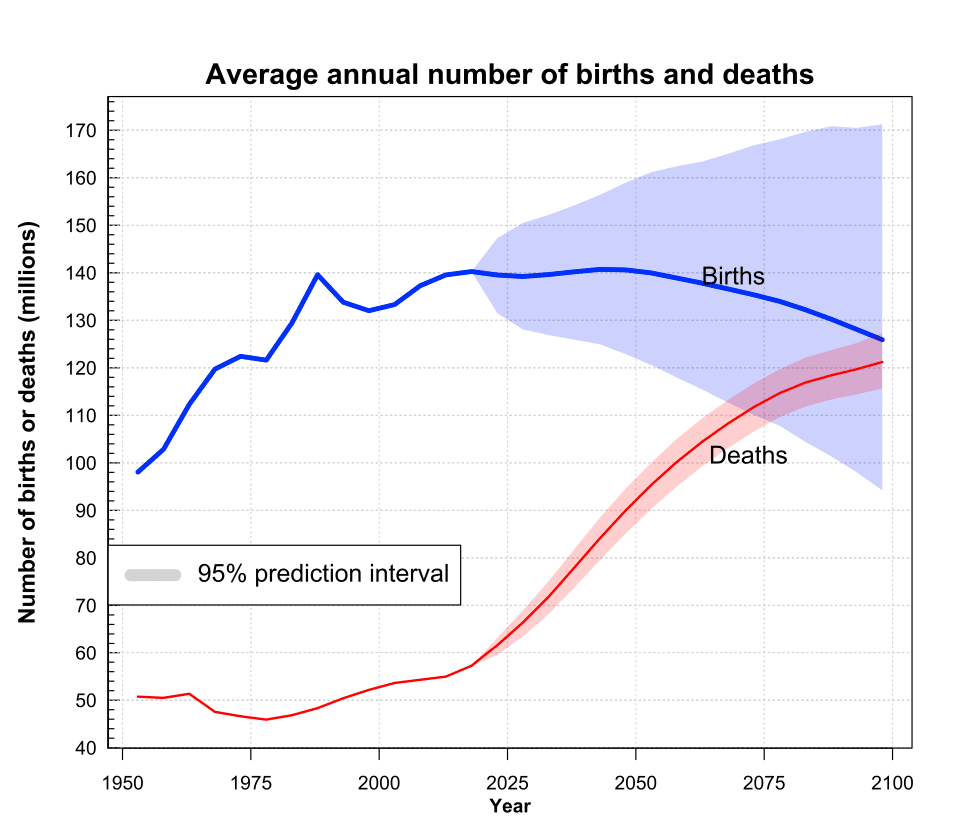

“World population growth could slow from 2065 onwards”

The Austrian demographer Wolfgang Lutz predicts a decline in the world’s population from 2065 onwards, whereas people are more likely to speak of a “demographic peril” by 2050. What can we say about the long-term evolution of the population?

If we look at the evolution of the annual population growth rate, it peaks at 2.1% in 1975 (i.e., a doubling every 33 years), then decreases to 1% today and could be cancelled out by 2065, when the population would begin to decline.

Nevertheless, when making predictions beyond 2050, past errors have taught us to handle forecasts with caution. For example, in 1994, the United Nations Population Division projected 163 million Iranians by 2050 and is now projecting 103 million after dropping to 94 million in 2014. In the meantime, fertility has dropped from 6.5 children per woman to 1.7, then back up to 1.9. The same is true for France, which in 1994 was projected to have 60 million inhabitants in 2050 and now projects 74 million. The rise in the birth rate at the end of the 1990s was poorly anticipated, as was net migration.

The median forecast of the United Nations is for continuous growth until 2100 and a population of 11.2 billion people by that date. Should we doubt this forecast in light of the work of Wolfgang Lutz?

There are several reasons to doubt it. The United Nations predicts a slow decline in fertility in intertropical Africa (between the Sahara and the Zambezi), even though this area accounts for a quarter of the world’s population growth and will account for three quarters by 2050. For example, the United Nations predicts that Niger, the world’s fertility champion, will drop from 7.3 children per woman to 4 in 2050 and 2.5 in 2100. However, much faster declines have occurred in the recent past. Between 1985 and 2005, fertility was halved in South Africa, from 5 to 2.6 children per woman, and it fell from 6.5 to 1.9 in Iran over the same period.

Projection of the world population until 2100 © ONU

Second, the UN predicts baby booms in several countries with very low fertility, such as South Korea (0.98) and Singapore (1.14). When fertility is below 1.3 children per woman, the United Nations systematically forecasts an increase to 1.5 by 2050, then to 1.7 or 1.8 by 2100. Indeed, fertility rates are rising again after sharp declines. We can cite the case of the former Eastern bloc countries, which experienced a sharp drop in fertility linked to the decline in the age of first child (from 23 to 28). However, once the transition was completed, there was a return to normal and a slight increase, albeit moderate. In Poland, the number of children per woman rose from 1.24 in 2004 to 1.41 in 2011 and in Hungary from 1.25 to 1.39 from 2011 to 2016. Then fertility fell back down. These mechanical effects are insufficient to justify the UN projections.

Is fertility misjudged?

On the whole, the decline in fertility is fairly poorly anticipated. Two-thirds of the world’s population live in a country where fertility is below two children per woman. In Latin America, the country – or region – with the highest fertility is French Guyana! Brazil has gone from 6.5 children per woman to 1.7 in 40 years.

Finally, the two most populous countries, China and India, are experiencing a rapid decline in fertility. In India, it is already 2.3 children per woman and in 23 out of 36 states below 2.1. In China, the abandonment of the one-child policy in 2017 generated a slight increase that has since fully subsided. But again, the demographic transition has a lag effect. China, to use this example, will only experience a decline in population from 2032 onwards.

Do you see other reasons for overestimating population growth?

Yes, the decline in mortality seems to be overestimated. This contributes to the demographic boom because people are living longer. However, over the past five years, the average age of death has increased much more slowly in developed countries. Possible causes include obesity, environmental degradation, and inequality. However, the UN expects a gain of five years of life by 2030 in these countries. This seems very optimistic.

What will the world population be in 2100?

It will not reach 11 billion, but rather 10 billion. We can say that the population explosion is almost over. The explosion of the 1990s and 2000s is behind us and the decline will come sooner than we think.

What could be the consequences of this demographic decline?

I see two major societal changes. The necessary delay in retirement in countries that have a pension system (to maintain it), and the entry of women into the workforce in countries where their participation rate is low. In both cases, this requires a change in mentality. We see this in France with retirement. The philosopher Marcel Gauchet talks about the “socialist moment” of life: free time, money and no more boss! Many people do not want to give it up.

As for health costs, they are really concentrated in the last months of people’s lives. The decline in mortality postpones health costs more than it increases them, all other things being equal.