Declining global IQ: reality or moral panic?

- IQ is a measure of an individual’s general intelligence within the population.

- It is a controversial measure, suspected of being used as a basis for discrimination in some countries, for example through selective migration or forced sterilisation.

- Since the middle of the 20th century, IQ has been rising worldwide, mainly in the BRIC countries.

- Since the 1990s, IQ has been rising more slowly, perhaps reaching a plateau due to the limits of the human brain.

- Studies warning of a decline in global IQ are being debated in the scientific community as being biased.

The first metric of intelligence came from the Binet-Simon test1 (named after a French psychologist and psychiatrist), used specifically to identify cognitive delay in children. A few years later, William Stern coined the term “intelligence quotient”: the index consists of dividing the “mental” age obtained by the child in the test by his or her physical age, then multiplying the ratio by 100. A 10-year-old child obtaining results equivalent to those of a 12-year-old would thus have an IQ of (12/10) x 100, or 120 points.

The IQ, now measured in both teenagers and adults, situates an individual’s general intelligence within his or her population (according to age, nationality, etc.), with all the values following a Gaussian curve. The so-called “standard” IQ (recalibrated approximately every decade) sets the mean value at 100 points and the standard deviation at 15. In today’s benchmark Wechsler tests2, 95% of the population has an IQ between two standard deviations, i.e. between 70 and 130 points.

The first half of the 20th century was marked by the controversial use of this index as a means of discrimination. Eugenicist theories, epitomised in particular by the nascent statistics of Francis Galton3, aimed to prove scientifically that the level of intelligence was innately lower in people of a certain characteristic (alcoholism, mental illness, etc.) or ethnicity. This framework of thought has prompted countries such as the United States to use IQ as the main criterion for selecting immigrants4, and even for forced sterilisation5.

But despite the variety of uses and models for IQ, recent meta-analyses6 make it possible to trace its evolution over the decades.

We are more intelligent than we used to be

The IQ scores of 300,000 people in 72 countries between 1948 and 2020 were compiled in the 2023 meta-analysis by Wongupparaj et al7. In the space of a century, they increased by around 30 points, or twice the standard deviation of the distribution of scores. But how can these values be compared when the index is recalibrated every ten years or so?

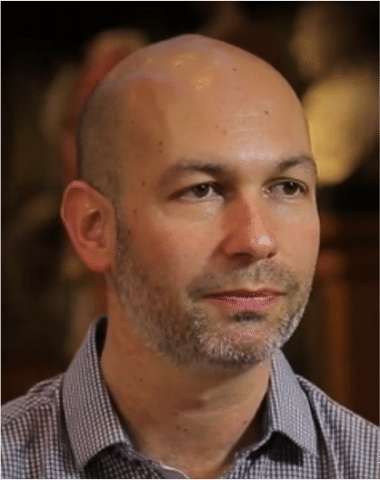

“It is the raw scores of the tests, before calibration, that are compared from one period to the next”, explains Franck Ramus. And not just any test, since the meta-analysis only considers the Raven Matrices to reassess IQ. This geometric test, which has remained unchanged since its creation in 1936, measures so-called “fluid” intelligence, enabling problem solving without the need for prior knowledge. It is therefore not subject to cultural obsolescence, as verbal tests typically are.

The Flynn effect is flattening out, but is not going away

The Flynn effect8 describes the gradual rise in the level of intelligence observed throughout the 20th century: improved nutrition9, access to or quality of medical care10 and technology11 are all favourable socio-economic conditions for the development of education and intelligence. According to the meta-analysis, it is in the BRICs (Brazil, Russia, India and China) that we are currently seeing the greatest increases (2.9 points per decade on average) compared with the richest and poorest countries (2 and 0.4 points respectively).

In short, IQ is rising and continuing to rise, but less markedly now: 2.4 points per decade between 1948 and 1985, compared with 1.8 between 1986 and 2020. “But trees can’t reach the sky, there are inevitably limits to what the human brain can do,” says Ramus. This stagnation, or reduction in the Flynn effect, can therefore be interpreted as an inevitable plateau in cerebral and cognitive development: just as an athlete’s performance is limited by the power of their muscles, so too is that of the brain (which is not a muscle!) from both a physiological and socio-economic point of view.

IQ decline: a moral panic

Edward Dutton and Richard Lynn (British anthropologist and psychologist) have put forward a theory in the media suggesting a recent decline in intelligence in several countries. However, the articles that support this hypothesis are riddled with methodological biases and dubious extrapolations. Whether because of the limited sample size (79 people) in Dutton and Lynn’s study of France12, or the fact that only certain types of test (numerical or verbal) were considered to be declining, despite an increase in others (abstract reasoning) in Norway13, such results remain on the fringes and do not meet with consensus in the scientific community.

“Whatever beliefs people may have about what’s going wrong, or what’s worse than before, the argument that IQ is falling seems to confirm them. So it’s understandable that it would be popular,” explains Ramus. The moral panic surrounding the decline in intelligence is not new: numerous environmental factors such as exposure to screens, endocrine disruptors or the deterioration of education are regularly singled out as potential culprits. Although these factors can have a negative impact on some people, both children and adults, none of them seems to cause a decline in IQ on a more global scale.