In France, several organisations are warning of a drop in academic standards, particularly in certain subjects such as French and mathematics. While some experts may qualify this observation, over the last twenty years or so, academic levels in these subjects have been falling (-11 points and ‑8 points respectively per decade for reading and mathematics). What are the causes? Could physical activity be one of the solutions?

A relative drop in levels of academic achievement

There is no doubt that academic standards have risen considerably since the 1970s, as Nadir Altinok and Claude Diebolt argue in an article for The Conversation1. However, if we look at the period from 2000 – the start of the surveys conducted by the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA)2 – to 2020, the results are less promising.

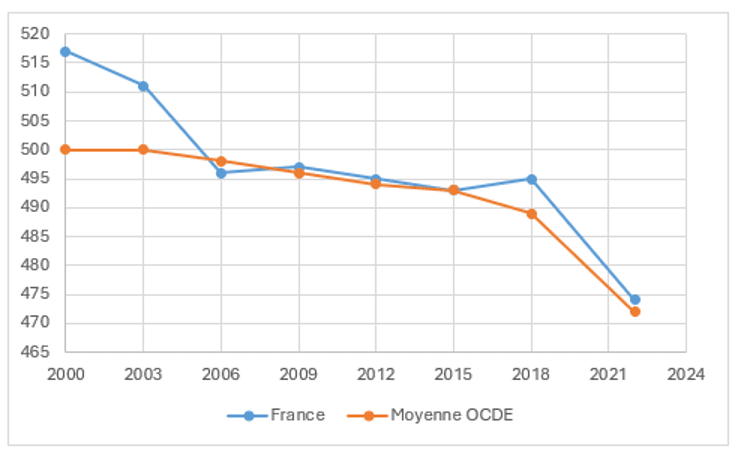

The authors of the article point to a worrying decline in school performance in reading and mathematics. However, Eric Roditi points out that “France’s PISA results in mathematics have always been more or less in line with the OECD average (see figure below). The only exception is the first PISA in 2000, when France was well above the OECD average.” Nevertheless, the researcher points out that “as this was the first PISA assessment, it is not possible to rule out possible survey response effects.” To explain this change in educational attainment, he says: “It is rather the proportion and level of ‘strong’ and ‘weak’ students that is changing. The figures also highlight the correlation, which is particularly marked in France, between social background and performance.” Indeed, as the data shows, the proportion of pupils experiencing difficulties will rise from 17% in 2003 to 30% in 2022. At the same time, the proportion of high-achieving pupils has fallen from 15% to 7% in 19 years3.

While social background seems to be a determining factor in school performance, we still need to understand the mechanisms involved. Sociology has long made a number of observations: low economic, social, educational and cultural capital. However, there is a forgotten capital that has its place alongside the macroscopic causes, and which can only be addressed by systemic and structural interventions: physical and cognitive capital.

Physical activity and school performance: how effective is it?

Before we can ask ourselves how physical activity can be effective, we first need to measure whether it really is. Research into the psychology of physical activity and education leaves no room for doubt. “The effectiveness of physical activity on school performance, particularly in mathematics, has been demonstrated by numerous randomised controlled studies,” points out Boris Cheval. In fact, in the February 2022 memo that the researcher co-authored for the French Ministry of Education, there was a 48% and 60% increase in cognitive and academic performance respectively5.

The researcher also points out that this effectiveness is undoubtedly underestimated. “When you measure the effectiveness of a drug, you compare the group receiving the substance with a group receiving an inert placebo. In research on physical activity, the control group remains a physically active group, because it would be unethical to ask children to stop doing anything.”

Finally, physical activity boasts something that no other treatment in the world has: the absence of side effects. “Physical activity has no adverse effects on learning. On the contrary, increasing the amount of physical activity and movement could improve the quality of learning. Increased activity never diminishes learning. We need to think about the quality of the time used, in other words, do less to do better,” insists Boris Cheval. A dynamic that has its equivalent in the world of work with the 4‑day week, which most studies show to be largely beneficial to productivity.

Mechanisms for improvement through physical activity

How might physical activity affect performance at school? Boris Cheval cites a number of biological mechanisms that could be behind the effect of physical activity on school performance: “physical activity triggers a deregulation of our body’s homeostasis (state of physiological equilibrium). This deregulation triggers a series of reactions and the release of substances (myokines, endorphins, BDNF, etc.). The result is an adaptation of all the organs in the human body, and in particular changes in the brain: angiogenesis, synaptogenesis, neurogenesis, etc. This means that physical activity enables our body and our brain to organise themselves better, to communicate better and therefore to function better, which in turn has an effect on cognitive performance and consequently on performance at school.”

What’s more, by mobilising high-level cognitive functions, physical activity could improve their use. “Certain activities, such as dance or team sports, enable us to use certain memory structures or executive functions that are essential in certain subjects, such as working memory or inhibition,” explains Boris Cheval. However, this raises the question of the transfer of skills from one field to another, which is still widely debated in psychological research.

The profile for ideal physical activity

If certain physical activities mobilise particular brain functions, this suggests that not all physical activities are equal. On the basis of all these elements, it is possible to create a profile of the ideal physical activity for improving performance at school. “It should be of moderate to high intensity, involve balance, coordination and learning, be cognitively demanding, be collective rather than solitary, and be practised at least three times a week,” says Boris Cheval.

An innovative aspect of the research explores the effect of the affective experience of physical activity. “The idea behind our current research is that a sporting experience with a positive connotation would not only be useful for persevering with the activity in the long term, but would also have a positive effect on the biological and cognitive effects of physical activity in the short term,” emphasises the researcher. It should be pointed out that this research is extremely recent and that more in-depth investigations are under way.

Physical activity as cognitive capital

At this stage, we know that physical activity is a real asset for improving performance at school, particularly in mathematics where the levels of evidence are the highest. In the same PISA report cited above, there was a specific increase of 86% in performance in mathematics as a result of physical activity, compared with 53% for languages.

The low level of political will (albeit with good intentions) does not give teachers the resources they need to implement these measures.

There is also a correlation between the level of physical activity and socio-economic status. In addition to economic and cultural capital, it would seem that inequalities also have an impact on people’s cognitive capital, from a very early age. Boris Cheval points out that “childhood is a critical period when we develop our cognitive reserve. Measures aimed at increasing physical activity are also more effective in populations with lower levels of physical activity or cognitive performance.”

Putting movement back at the heart of schooling

To overcome these differences in cognitive capital, there is only one solution: put movement back at the heart of school and learning. “Movement is essential for all learning. It helps to create new cognitive habits by improving cognitive functions. We need to get away from the idea that learning should always be done sitting down and as quietly as possible,” comments a perplexed Boris Cheval.

Unfortunately, architectural and political dynamics are hampering this objective. “The low level of political will (albeit with good intentions) does not give teachers the resources they need to implement these measures. The result is a feeling of coercion and territorial inequalities that persists and is getting worse,” deplores Boris Cheval.

To counter these trends, strong measures are needed. Examples include training and support for primary school teachers in setting up quality activities or economic support. Teachers need to feel empowered and supported. Theories in the psychology of motivation, the theory of self-determination and the theory of planned behaviour have clearly demonstrated that in order to adhere to and persevere in a behaviour, it is above all necessary to feel autonomous, competent and to create a bond. Without these ingredients, the government’s good intentions will probably be in vain, and the hours of physical education and sport on the curriculum will continue to be the first to be cancelled as necessary.

Physical activity beyond academic performance

In conclusion, it is important to remember that physical activity is not just a catalyst for academic performance. Above all, it has a major impact on physical and mental health. There is an urgent need to take action with regard to the lifestyles of the very young. We need to combat the loss of cardio-respiratory capacity, obesity, type‑2 diabetes and all these increasingly common early onset pathologies. Without good physical health, there can be no quality education.

Proper physical education at school instils a taste for effort, competition, cooperation and surpassing oneself. So many skills that are useful in social and professional life. Anchoring physical activity in a positive emotional experience helps to maintain well-being and physical and mental health. At the same time, it’s a way of preventing socio-economic and gender inequalities.