Covid-19: why there will be no baby boom

Early on in the pandemic, as governments were starting to realise the magnitude of the Covid-19 crisis and the first wave of stay-at-home orders with business and school closures were being implemented, news stories about what this new situation would mean for the fertility rate started appearing. Visibly, as the virus was running wild, so was our fantasy.

These early news stories almost entirely focused on the positive effects of stay-at-home orders on couples’ intercourse. As such, a coming baby boom was being hailed, fuelled by widely circulating stories of increased births that followed 9 months after stay-at-home orders during hurricanes or snowstorms. Some newspapers went so far as to christen this novel generation of expected children the “Coronials”.

Myth or reality?

Most experts, however, were sceptical of this narrative. In fact, the research we have on past sudden stay-at-home orders is much more timid in its conclusions than the popular myths that took hold. A rigorous study of the great 1965 New York electricity blackout found no effect on the fertility rate 1and, while light storm warnings lead to a 2.1% uptick in births 9 months later, strong hurricane warnings lead to a ~2.2% decrease in the number of newborns nine months later2.

Moreover, there already exists a substantial body of research on how human fertility rates tend to play out during and after pandemics; the findings of which suggest that what was still being excitedly claimed on afternoon television by couples’ councillors was unequivocally false. History tells us that pandemics do not drive baby booms. Rather, it is the opposite: most of the time they result in a severe baby bust.

Lessons from Spanish Flu

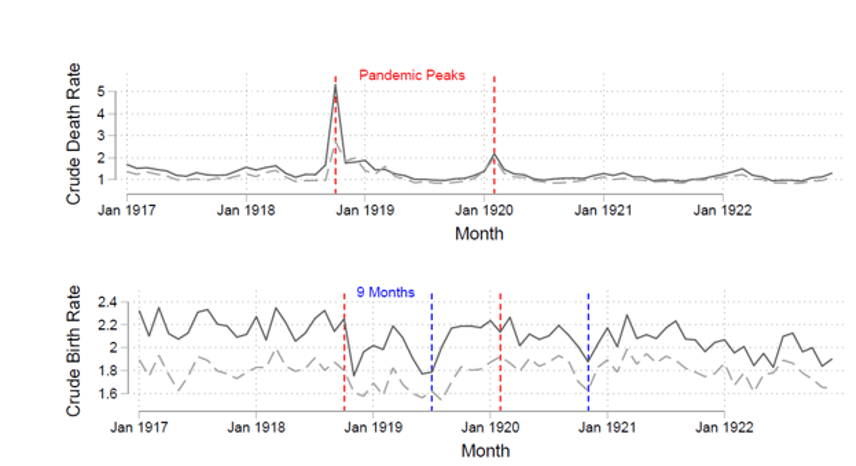

The closest historical analogy we can look back to is the 1918 Spanish Flu, another truly global pandemic – although it should be noted that it was considerably more deadly for young people than Covid-19, with the majority of excess mortality in 1918 happening among the 20–40 year old population 3. The fertility lessons from the Spanish flu are clear: whether you look in France, the United States or Sweden 4, birth rates in all countries studied dropped substantially, by about 13% in the US and by about 8% in Sweden as soon as the pandemic broke out.

Shortly after the first lockdown orders were given in France, we decided to look at how U.S. cities that implemented non-pharmaceutical interventions, such as stay-at-home orders, business, and school closures during the 1918 pandemic fared in terms of fertility 5. As could be expected, fertility plummeted by an average of 10–15% due to Spanish Flu in the cities we studied. However, the drop was less pronounced in cities that implemented longer lasting and stricter measures.

As such, we considered the possibility that maybe there was something to the much-heralded link between staying at home and increased intercourse after all? However, another striking characteristic of cities that implemented longer lockdowns was that they had considerably less severe pandemic outbreaks with much lower numbers of mortality.

Therefore, another possible explanation was that lockdowns only increased birth rates because they reduced the negative effects that a strong pandemic outbreak had on people’s decision to have babies. To control for that we considered the strength of pandemic outbreak in our statistical models. After doing so, the net effect of lockdowns on fertility rate was negative – meaning less babies were born as a direct consequence of lockdowns, beyond their effects on pandemic strength.

Covid-babies

Coming back to the current pandemic, the first data-based insights on what to expect come from surveys and from google search data. Surveys conducted in March and April of 2020 in France, Germany, Spain, Italy, and the UK showed that people aged 18–34 were increasingly planning to postpone or abandon their childbearing plans for 2020. In Italy, where the outbreak was particularly strong, only 26% of individuals that planned to get pregnant in 2020 said they still had those plans, with 37% planning to postpone and 37% saying they had abandoned their child plans. In France only 14% reported abandoning the child plans but 51% did report that they would postpone them if possible. 6.

Another approach was to use Google Searches. It is possible to predict fertility rates based on the frequency of common search terms, such as “ovulation”, “pregnancy test” and “morning sickness” amongst others. When this analysis was applied to the United States, this type of model foresees a fertility drop of 15% for the coming months. 7.

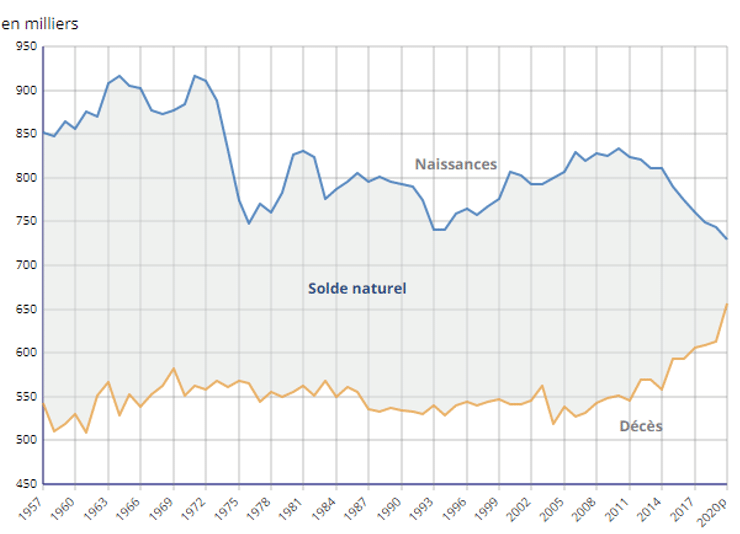

Finally, we are also starting to get a first glance at fertility data from 2020 and, in doing so, we see that they support the baby bust hypothesis. In France there was a fertility drop of 2% for the year and in the U.S. one of 3.8%, which however was 8% for the month of December, when the pandemic effects started to really show 8.

Many questions remain. Did stay-at-home orders and school closures have an additional effect that was independent of the pandemic this time around? Did economic aid, in the places where it was available, reassure people to continue their family planning and thereby cushion the fertility drop? Will the predicted economic boom following the Covid crisis lead to catchup fertility, making up for the foregone births? As researchers continue to evaluate these questions, for the short-term we must contend with a world in which less babies are one of the many consequences the virus has had on our lives.