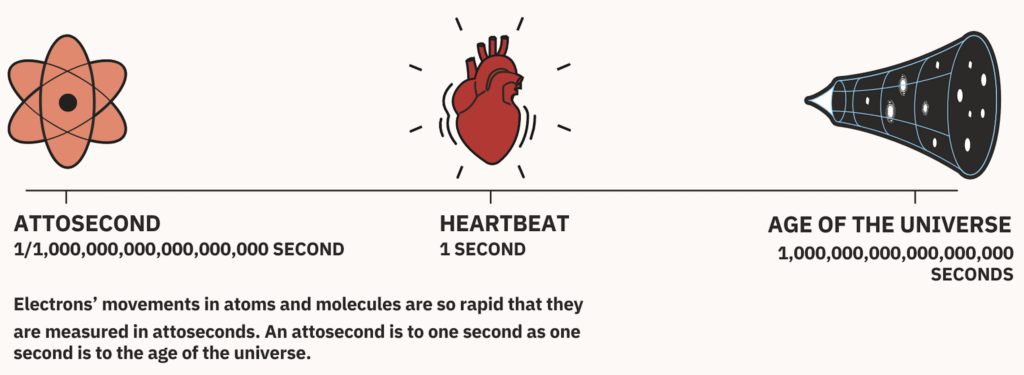

The 2023 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded for the development of experimental methods for generating attosecond laser pulses (10–18 seconds), flashes with a speed of around one billionth of a billionth of a second. They are useful for studying the dynamics of electrons in matter. Three scientists received awards : Pierre Agostini, Ferenc Krausz and Anne L’Huillier.

Why generate attosecond laser pulses ?

Laser pulses are like camera flashes that allow us to freeze and observe the movement of matter. The faster the flash, the faster the dynamics we can observe. Previously, we were able to generate laser pulses in the femtosecond range (10-15 seconds). This is the speed at which atomic nuclei move during chemical reactions. By getting down to the attosecond scale, we are now able to observe the rearrangements of the electrons themselves : this process is extremely rapid – it was even considered instantaneous in many theoretical models !

Why is it important to observe electron dynamics ?

Electron rearrangements take place during critical stages in the transformation of atoms, molecules and materials. Understanding these dynamics is a fundamental issue in physics and chemistry. Attosecond lasers have opened the way to unprecedented experimental observation of nature. Many questions can be addressed : how does the electron cloud reorganise after a rapid disturbance, and how long does it take ? How does this influence the movement of the nucleus ? Can we control and steer the rearrangement of electrons ?

Why is it so difficult to characterise the dynamics of electrons ?

Quantum mechanics provides us with the equations that describe the behaviour of matter, including electrons. But solving these equations accurately requires enormous computing power. And that’s even for a very simple atom like helium, made up of a nucleus and two electrons… So, we’re a long way from moving on to more complex atoms, or even molecules !

A few reminders about physics

What are the objects around us made of ? Let’s delve into the infinitely small by taking the example of water. Water is made up of molecules, the basic structures of matter. A glass of pure water contains a large quantity of H2O molecules. The molecules themselves are made up of atoms : 2 hydrogen atoms and 1 oxygen atom in our example. On an even smaller scale, atoms are made up of a nucleus around which electrons revolve. Electrons are essential to the bonds in molecules and are involved in chemical reactions. They are also involved in physics, contributing to conductivity, magnetism, electromagnetic radiation, etc.

The only solution is to use approximations to simplify the calculations. These approximations also provide simplified mental models for thinking about this complex physics. It is therefore essential that they are accurate. This is where attosecond pulses come in : they provide extremely precise experimental measurements, which are invaluable for establishing and validating these approximations.

What scientific discoveries have attosecond pulses led to ?

In electronics, current is governed by switches controlled by electromagnetic fields. For example, an electric field is applied to a transistor which, depending on whether or not the field is activated, either lets the current through or blocks it. To explore the speed limitations of these switches, laser pulses are used instead of transistors. Attosecond physics has developed the fastest and most precise electromagnetic fields in existence. Scientists at Garching in Germany and Graz in Austria have used them to test how quickly it is possible to switch from one mode to another. The result is that at around one petahertz, or one million gigahertz, there is an upper limit for well-controlled optoelectronic processes1.

Other advances relate to the time taken for an electron to leave its atom after absorbing a photon. In 2010, Ferenc Krausz’s team published experiments that showed a difference of 20 attoseconds between the emissions from two electron layers of a neon atom2. After seven years of scientific debate, Anne L’Huillier and her team were able to clarify the origins of this delay as a correlation between neon electrons3.

Have attosecond pulses become part of our everyday lives ?

No, that’s a long way off. But the scientific scope for their use is constantly expanding. Chemists have been taking an interest in them since 2010. One of their aims is to optimise certain chemical reactions. However, electronic dynamics are highly complex and difficult to control, so research is still at a fundamental stage. Molecular biologists are using them to observe how and at what speed electric charge migrates along large molecules after the sudden removal of an electron. This enables them to better understand the damage caused to DNA by certain types of radiation. The semiconductor industry is also interested in the imaging possibilities offered by these lasers.

How is it possible to generate such a short laser pulse ?

The method most widely used today is that discovered by Anne L’Huillier : a laser (in the near infrared or visible range) is directed at gas atoms. Under the right conditions, the laser’s electric field pulls on the electrons, steering them along trajectories around their atoms and causing them to collide with their atoms. These synchronised collisions between all the atoms generate attosecond pulses. We now know that it is also possible to use very thin solids, plasma mirrors or even free electron lasers. Technically, it’s not complicated to generate trains of attosecond pulses, but you need to know how to characterise them. As the attosecond sources developed today become more powerful, they will be able to address new processes.

What is the future of this field ?

The systems studied are becoming more complex : molecules are larger, solids are structured on a nanometric scale… The pulses will be shorter and shorter, and the zeptosecond frontier – thousandths of an attosecond – will fall. At this scale, it will be possible to make similar observations of protons and neutrons bound together in the nuclei of atoms.

Another potential approach is to concentrate energy over time to unprecedented powers. Quantum theory shows that with a sufficiently strong electromagnetic field, it is possible to separate matter/antimatter pairs from the quantum vacuum. In other words, light can be transformed into matter. However, there is currently no instrument that can deliver the necessary power. Plasma mirrors, which are of major interest to the award-winning team, are a promising way4 of compressing the most intense lasers currently available (petawatt) in time and space, such as APOLLON, which is managed by the laboratory for the use of intense lasers at the Institut Polytechnique de Paris and Sorbonne University. The aim is to test fundamental theories in extreme conditions never before encountered.