Why it’s not so easy to calculate global greenhouse gas emissions

- According to the national greenhouse gas inventories, the largest emitters of GHGs are, in order, China, the US and the EU.

- However, levels of accuracy may vary from one sector to another, as GHG emissions are not always calculated using the same set of parameters.

- The choice of GHG emissions indicator significantly affects the results and even the ranking of emitting countries.

- The carbon footprint, which takes into account the emissions linked to the consumption of citizens, including imports, is particularly relevant.

- In 2019, half the population was responsible for 12% of global emissions compared to the richest who were responsible for almost 50%.

Who is responsible for world greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions? Which countries are exemplary, which citizens are major contributors? The answer is far from simple. And for good reason: there is no direct measurement of GHG emissions at a national level. The measurement of GHG emissions from human activities is based on indirect estimates. For example, fuel sales data can be cross-referenced with their emission factor (i.e. the amount of GHG emitted per unit of energy) to estimate transport-related emissions. This can be done for each of the GHG emitting or capturing sectors: energy, industrial processes, agriculture, land use and waste.

Gaps in the indicator

China leads with 11.2 Gt CO2e emitted in 2014, followed by the United States (5.7 Gt CO2e in 2019), the European Union (3.3 Gt CO2e in 2019) and India (2.5 Gt CO2e in 2016). These figures are those of the national greenhouse gas inventories, regulated by the Kyoto Protocol since 2005. They account for seven GHGs (CO2, CH4, N2O, HFCs, PFCs, SF6 and NF3) using a method defined by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Each country in Annex I of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (i.e. 43 States, including the European Union1) is required to submit its national GHG inventory each year. This obligation will be extended to all member countries from 2024.

The levels used vary from one sector to another, from one country to another.

Is this calculation method the right one to use? “This indicator is intended for political purposes and is very useful for defining the tools for implementing national strategies to reduce GHG emissions,” says Etienne Mathias, a land sector expert at Citepa, the organisation responsible for calculating the inventory in France. “However, it has several shortcomings for an international comparison. The IPCC defines guidelines with different levels of precision,” explains Julien Vincent, head of inventory methodology at Citepa.

Emissions can be calculated on the basis of default parameters (level 1), representative of the national level (level 2), or even refined at the scale of a GHG emission site (level 3). The levels used vary from one sector to another, from one country to another. While this has little influence on the calculation of energy-related CO2 emissions, other sectors can show great variability between states. “Fugitive emissions from oil and gas extraction (e.g. methane leaks) have very high levels of uncertainty, even for developed countries,” says Julien Vincent. Etienne Mathias adds: “Releases from agriculture and especially the land sector present even greater uncertainties, which can be as high as several million tonnes of GHGs, particularly as many undeveloped countries have little activity data and emission factors.” Another limitation is that only 48 countries have submitted at least one inventory to date.

New indicator, new results

To fill these gaps, let us look at one of the projects providing harmonised GHG emission maps across the globe: the ClimateWatch indicator2 from the World Resources Institute. It compiles several international databases. While the ranking remains unchanged, this time it shows that the 10 highest emitting countries together emit more GHGs than the rest of the world. For 2019, China’s total is 12 Gt CO2e (up sharply since the early 2000s), compared with 19.7 Gt CO2e for the rest of the world.

Beware the indicator used

The choice of indicator can strongly influence the ranking. For example, whether or not to include the land sector in the calculation (often indicated under the abbreviation LULUCF). This sector takes into account land use, land-use change and forests: carbon sources and sinks are therefore accounted for. “If the objective is to look at the evolution of emissions, it is logical to exclude carbon sinks,” says Mathias. While China and the US remain at the top of the ranking, India and the EU are now neck and neck when the land sector is excluded from the balance sheet. On the other hand, Indonesia has dropped from 8th to 5th place in the ranking when LULUCF is included, from 1 Gt CO2e to 1.96 Gt CO2e: this reflects the significant deforestation in the country.Another point to consider is the emissions taken into account. Some indicators include all GHGs (expressed in CO2e), others only CO2. This reduces the weight of certain sectors in the balance sheet, such as agriculture, which mainly emits methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O).

So why do countries like China have such high emissions? Partly because of their population size. Based on the ClimateWatch indicator for 2019, the highest emitting citizens are those of the Solomon Islands (69.2 t CO2e/capita/year), Qatar (40.5 t CO2e/capita/year) and Bahrain (33.1 t CO2e/capita/year). Each Chinese citizen contributes 8.41 t CO2e each year. In India, the world’s fourth largest emitter of GHGs, emissions amount to only 2.4 tonnes of CO2e/inhab/yr.

Carbon footprint upsets the rankings

Another interesting aspect is carbon footprinting. Until now, the indicators mentioned only reflect the emissions of citizens within their own country. Some countries, such as China, are major exporters of goods and services. The carbon footprint, on the other hand, takes into account the emissions linked to the consumption of citizens. It adds up the emissions of households, domestic production, and imports, minus the emissions associated with exports. For example, in the case of France, while territorial emissions amount to 5.4 t CO2e/inhabitant/year, the carbon footprint will rise to 8.9 t CO2e/inhabitant/year in 2021 according to the Service des données et études statistiques3. Indeed, more than half of France’s carbon footprint comes from imported goods and services and imported raw materials or semi-finished products.

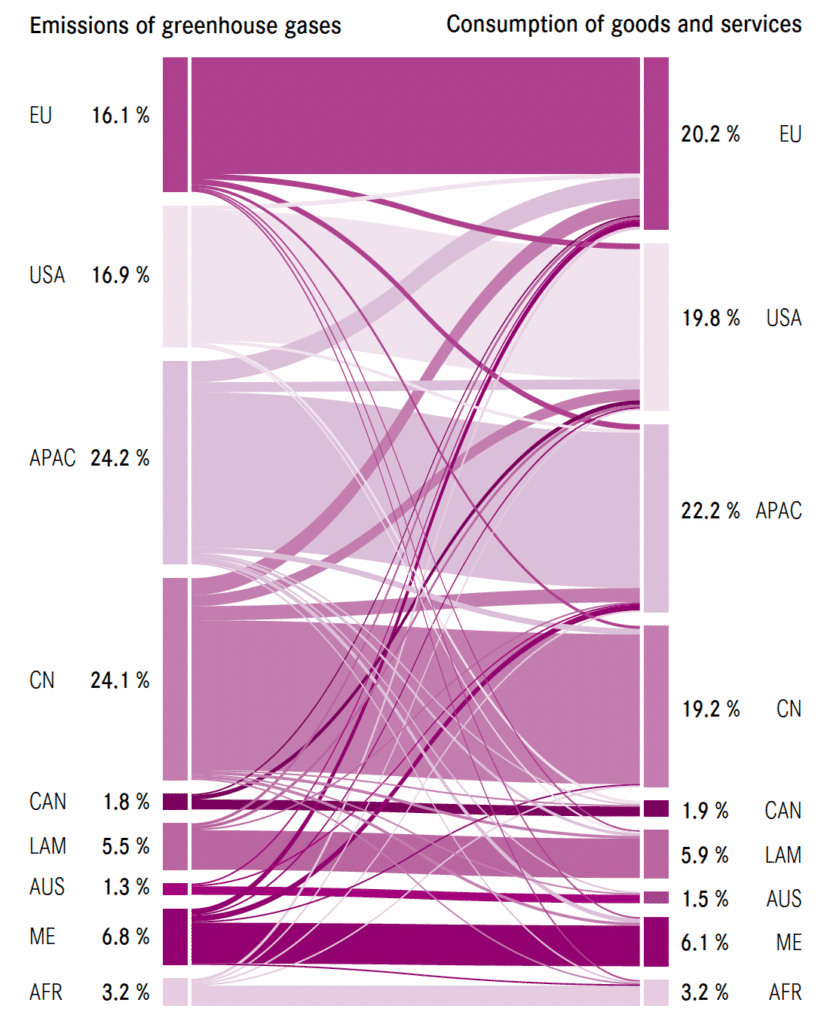

There is no standardized method for calculating carbon footprints on a global level. According to the Exiobase database4, a significant part of China’s emissions is due to the production of goods and services for Europe or the US. While China accounts for 24.1% of global GHG emissions, this figure drops to 19.2% when considering its carbon footprint, behind Europe (20.2% of the global carbon footprint) and the US (19.8% of the global carbon footprint).

There is no standardised method for calculating carbon footprints on a global level.

“You have to keep in mind what each of the indicators illustrates, they all have a different purpose,” says Julien Vincent. “For example, per capita emissions are averages and do not represent income levels and other social inequalities.” In an article published in Nature Sustainability in 20225, Lucas Chancel estimates that in 2019, half the population was responsible for 12% of global GHG emissions. The richest 10% were responsible for 48% of global GHG emissions in the same year.