The goal is clear: to keep global warming “well below +2°C” by 2100 (relative to the pre-industrial era). However, global efforts to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions are insufficient. To achieve the UN’s sustainable development goals, it is now critical for decision-makers worldwide to be more ambitious in terms of both mitigation as well as ecosystem and societal adaptation. This raises the question as to what opportunities are provided by the ocean to support international climate action.

“More than just a victim, the ocean is also a source of solutions”

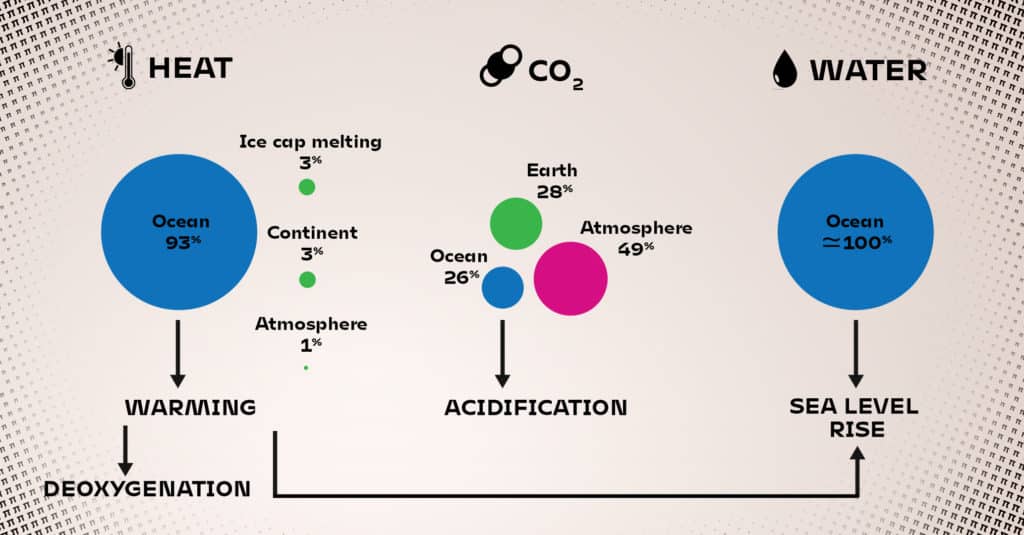

The ocean – including landlocked and marginal seas – is a ‘climate regulator’ for the planet (Fig. 1). Since the 1970s, it has absorbed 93% of excess heat, limiting the warming of the atmosphere. It has also sequestered 25–30% of man-made CO2 emissions since 1750 and has received almost all the water released by melting glaciers and polar ice caps. Without the ocean, climate change would be much more intense than it is today.

However, this has come at the cost of significant consequences on the chemical and physical processes in the ocean, such as warming, acidification, deoxygenation, and rising sea levels. These upheavals have already had detectable implications for ecosystems and their services, and for societies around the world12. The ocean is however more than just a victim of climate change, it is also a source of potential solutions. We have assessed the main ocean-based measures that have been described in the scientific literature3. They cover both mitigation and adaptation45 and refer to addressing the causes of climate change, promoting biological, ecological and societal adaptation, and managing solar radiation.

Making categories for more efficient action

According to different criteria – effectiveness, feasibility, duration of effects, co-benefits, disadvantages, cost-effectiveness, and governability – the ocean-based measures we assessed can be grouped into 4 categories: Decisive, Low Regret, Unproven, and Risky. Such categorisation is intended to guide the development and implementation of climate policies, combining mitigation and adaptation, at various stages of action: from the international level, under the framework of the revision of Nationally Determined Contributions, to the local level, through concrete and planned action strategies, and passing through the national level when defining Climate Plans.

This categorisation suggests that, more ambitious contributions should stimulate action based on ocean-based solutions by prioritising Decisive (e.g. marine renewable energy) and Low Regret measures (e.g. conservation and restoration of coastal vegetation, involvement of local communities in adaptation actions, or revision of risk reduction policies to better take into account anticipated climate change).

Unproven measures have very high potential effectiveness but have so far been through little or no testing and as some of them, such as improving productivity in the open sea and alkalinisation, may have high potential drawbacks. There is a need to improve knowledge of these Unproven measures as well as those that are considered Risky due to their potential negative collateral effects (e.g. solar radiation management).

No action without planning

It is also crucial to note that the relevance of some measures will depend on the context in which they are deployed. While infrastructure-based adaptation (e.g. coastal dykes) may, in some situations, offer a sustainable solution for climate risk reduction (Decisive), in other contexts it will prove counterproductive in the long term (Risky). Similarly, the relocation of people and economic activities can be decisive in the long term for low-lying coastal areas (Decisive), provided that it is supported by a long planning and support process beforehand, and without which there is a high risk of increasing the vulnerability of relocated populations and activities (Risky).

Another level of complexity lies in the fact that none of the measures will be sufficient on their own, and therefore that the design of any robust “climate solution” necessarily relies on the identification of context-specific combinations of responses. While Decisive and Low Regret measures are clearly priorities for action, it is important to understand that full implementation of Decisive measures will not completely eliminate coastal risks. Also, the long-term effectiveness of Low Regret measures, particularly nature-based solutions, will be determined by the future level of global warming. Therefore, scientific research must continue to explore the field of Unproven solutions and to understand the conditions of application of Risky solutions.

This element of diagnosis refers to a key principle of climate action: rather than thinking in terms of individual, idealised solutions, a more promising avenue consists of thinking in terms of mitigation and adaptation “trajectories”. The “trajectory” lens refers to the sequencing of a diversity of responses over time, according to new knowledge on climate change and its impacts at both global and local levels.