Traffic congestion in urban areas is nothing new. The city of Paris, known for its traffic jams, tried to improve urban flow by increasing the number of lanes in the 1980s. But this attempt led to what is known as the Bræss paradox. That is, adding or modifying roads (and thus the number of lanes) modifies the flow of traffic to the point that it actually reduces overall efficiency instead of reducing congestion. In addition, the problem of congestion is also closely linked to the issue of pollution, in particular air pollution. According to the WHO, air pollution is responsible for 4.2 million premature deaths per year worldwide1, caused in particular by exposure to (ultra)fine particles in cities. In response to this growing public health crisis, several lane closure policies have been introduced, although they are regularly challenged due to the lack of evidence regarding their supposed effect on air quality.

Greener centres, greyer suburbs

In 2016, the City of Paris closed a central road that runs along the river, known as the “voie Georges-Pompidou” or “les voies sur Berges”. Used by around 40,000 vehicles per day over a distance of 3.3 km, this stretch of road provided access to Paris and certain suburbs for commuters. While the closure of this thoroughfare has had a number of beneficial effects within the city – such as air quality, need for more public space, and reduction in noise pollution – commuters have tended to divert journeys to other routes rather than take public transport. As a result, the west to east-bound lanes of the southern ring road (“périphérique-sud”) have seen their congestion increase by 15%, adding two minutes on average to commuter’s car journeys over a distance of 10km.

The problem of congestion has therefore just been moved from the banks of the Seine to the suburbs, where citizens are already experiencing an overall increase in respiratory complications among their residents. According to a study conducted by the Airparif association2, 5,040 premature deaths in the Greater Paris region and nearly 7,920 in Ile-de-France were recorded between 2017 and 2019. There is no indication that this increase is a direct result of the increase in congestion in the city, but it is certainly not improving the situation.

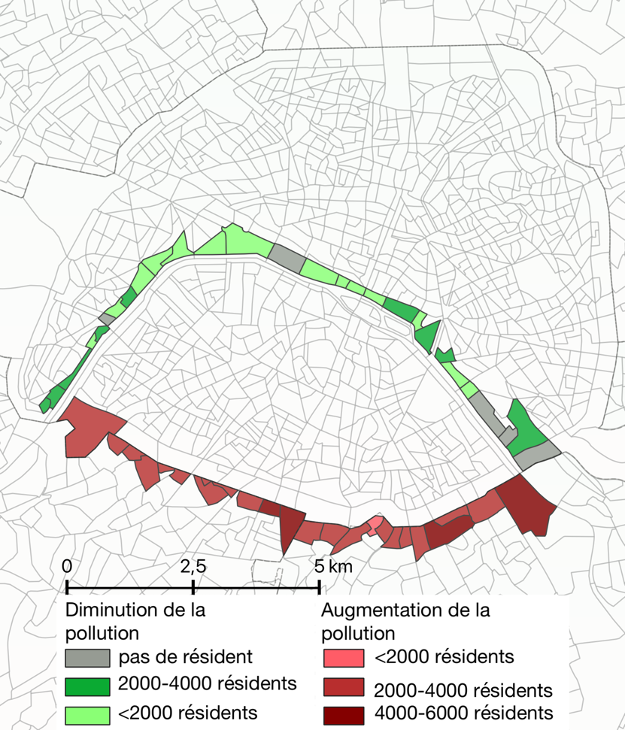

Air pollution has therefore shifted, increasing the NO2 concentration in the air to 70μg/m3 around the eastern ring road (“périphérique-est”) in 2015. Whereas, in the centre, the pollution rate remains around 40μg/m3. This indicates that areas which were already heavily affected by pollution problems are becoming even more so and that the impact on health, although difficult to quantify, could be significant in years to come.

Map of Paris showing exposure to pollution3

Our analysis of the subject4 seems to indicate that the reason why drivers do not change their mode of transport is because they are unable to do so. As the growth of public transport has not kept up with demand, public policies penalise “trapped drivers” living in the suburbs who continue to use their car due to the lack of alternatives. It is therefore crucial to integrate alternatives into future measures in order to have positive long-term effects on the whole region and to avoid a perpetual shift in road congestion.

What are the alternatives?

Other solutions have been considered abroad. Some cities, such as London and Seoul, have introduced congestion charges, the cost of which is calculated according to the average impact of a vehicle in terms of congestion (i.e. “congestion charge” in London). However, it is difficult to apply such a fee in France, where political tensions around environmental taxes are very high. The increase in the carbon tax in 2018, which was finally cancelled following the “Gilets jaunes” movement, is one of the most blatant examples of the opposition by the people of France to this type of taxation. Moreover, it would serve to increase social inequalities because in France, unlike in other countries such as the United States, the least well-off part of the population lives in the suburbs.

There are a number of ideas which could be implemented to reduce congestion on the roads without aggravating existing social divisions, in particular the idea of closing and opening the riverbanks at different times of the day. In order to do this, it is necessary to consider how to optimise the use of the riverbanks in relation to the amenities they provide. Because, when the lanes are closed, they are used for economic purposes. For example, it could be beneficial to close off the Berges to traffic outside of rush hour on weekdays (8am-6pm) to ease traffic for commuters working in the capital and at the same time allow for the use of amenities which are not necessarily required during peak hours.

However, these solutions all entail different costs, particularly for opening and closing the banks, which would require staff. The right solutions are complex and need to be carefully considered so that all sides can find a solution that benefits them.