IPCC report: three things you need to know

- The latest IPCC report, published on 4 th April 2022, is a summary of the current situation of global warming, with the particularity of proposing solutions to combat this phenomenon.

- The conclusion is that we can still act, but we must do so now.

- The goal set by the Paris Agreement in 2015 seems to be achievable but requires a radical reduction in our GHG emissions in all sectors.

- Limiting global warming requires major transitions in the energy sector, involving a substantial reduction in the use of fossil fuels.

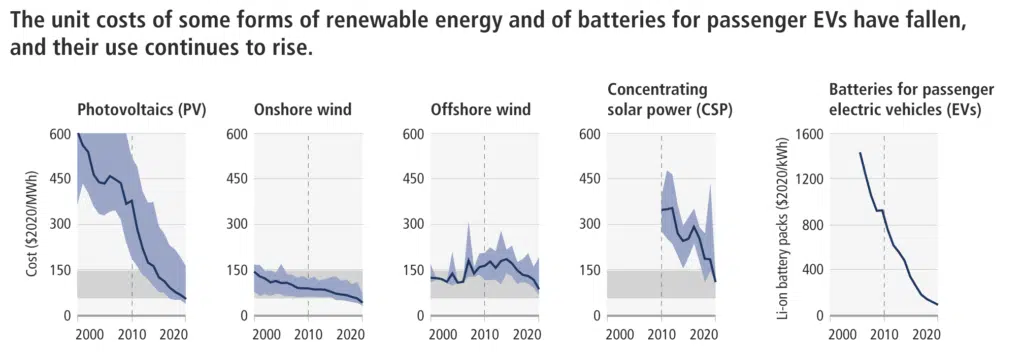

- Since the 5 th IPCC report, the costs of solar and wind power have fallen, and a growing range of policies and laws have improved energy efficiency and accelerated the deployment of renewable energy.

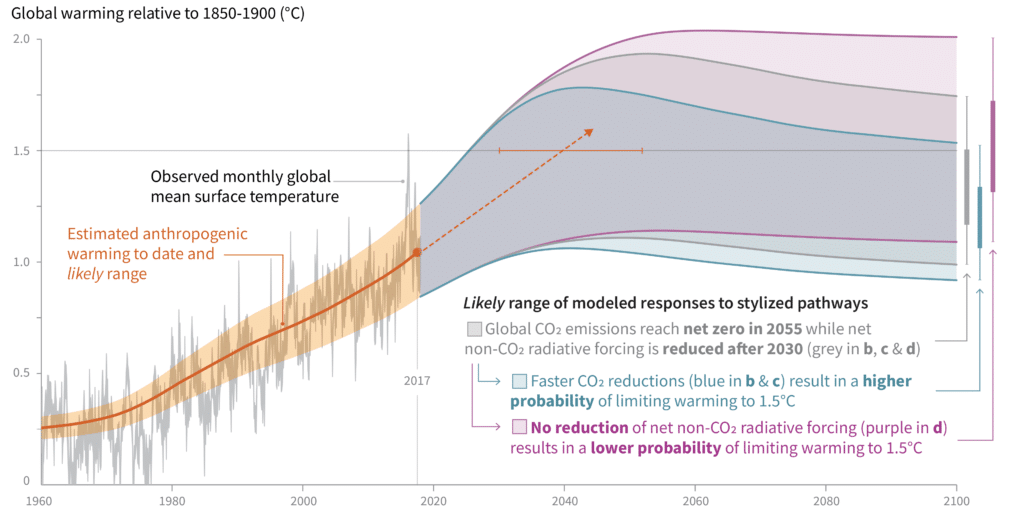

The latest IPCC report, published on 4 April 2022 1, is a summary of the current situation of global warming, with the particularity of proposing solutions to combat this phenomenon. All these recommendations, together with estimates and scenarios for the best ways to implement them, are presented as the pathway to avoid scenarios where global temperatures rise above 1.5°C – as described in the first report of this series, published in August 2021 2. The conclusion is that we can still act, but we must do so now. Indeed, it shows that without immediate and massive reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, it will be impossible to keep global warming below 2°C.

“Global temperature will stabilise when carbon dioxide emissions reach net zero,” explains Philippe Drobinski, professor of climate science and director of the Laboratoire de Météorologie Dynamique and the Energie4Climate centre at Institut Polytechnique de Paris. “For a warming threshold of 1.5°C, this objective for carbon neutrality must be reached by the early 2050s. Limiting warming to around 2°C requires that global greenhouse gas emissions peak by 2025 at the latest, reduced by a quarter by 2030 and reach net zero carbon dioxide emissions worldwide by the early 2070s.”

It’s not too late

Patricia Crifo, professor of economics at École Polytechnique and deputy director of the Energy4Climate centre (IP Paris), says we can still act. “We often read that there is a climate inertia of several decades, and that efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions will somehow be futile in the short to medium term,” she says. “While many of the changes caused by past and future greenhouse gas emissions are indeed irreversible (notably impacts on the ocean, ice caps and global sea levels), the report points out that if we cut emissions sharply soon, we will see effects on air quality within a few years, on global surface temperature within about 20 years, and on many other climate impact factors in the longer term. So, we can influence our climate future and every action counts.”

The target, agreed in the Paris Agreement in 2015, still seems achievable, but requires a radical reduction in our GHG emissions, across all sectors – whilst bearing in mind that the impacts of various sectors differ in their emissions. This is the case for the agriculture, forestry, and other land use (AFOLU) sector, which accounts for 23% of global GHG emissions with a total of 12 GtCO2 equivalent/year 4. However, despite the large-scale emission reductions, as well as their enhanced soil absorption, the sector could achieve, the IPCC remains stoic. In the report we find, “[these large-scale reductions] cannot fully compensate for delayed actions in other sectors”.

The energy transition must happen

“Limiting global warming requires major transitions in the energy sector, involving substantial reductions in fossil fuel use, widespread electrification, improved energy efficiency and the use of alternative fuels,” says Philippe Drobinski. “Since the 5th IPCC report, the costs of solar, wind and battery power have fallen. A growing range of policies and laws have improved energy efficiency, reduced deforestation rates, and accelerated the deployment of renewable energy.”

The report points to the significant potential for reducing emissions from cities through reduced energy consumption, electrification of transport in combination with low-emission energy sources and improved carbon absorption and storage using nature. Reducing emissions in industry means using materials more efficiently, reusing and recycling products and reducing waste. This must be accompanied by new production processes, low or zero emission electricity, hydrogen and, where necessary, carbon capture and storage.

He adds, “accelerated and equitable climate action to mitigate and adapt to the impacts of climate change is essential for sustainable development. The options proposed would benefit biodiversity, climate change adaptation and secure livelihoods. Some can absorb and store carbon and, at the same time, help communities to limit the impacts associated with climate change.”

No individual effectiveness without structural change

Another angle proposed by the IPCC is reduction in demand. To reduce our environmental impacts, production should no longer be based on quantity, but only on what is needed. This includes changes in infrastructure use, adoption of end-use technologies, as well as socio-cultural and behavioural changes. According to the IPCC, these “demand-side measures, taken or to be taken, can reduce global GHG emissions in the end-use sectors by 40–70% by 2050 compared to the reference scenarios.”

Julie Mayer, assistant professor at École Polytechnique and researcher at I3-CRG (IP Paris), conducts research on the organisational transformations underlying the energy and ecological transition. She explains that “this is the first time that an IPCC report has given so much space to the issue of sobriety. This shows that this concept is becoming essential in the fight against global warming, and reinforces its legitimacy.”

Through the term “energy conservation”, the IPCC places sobriety as one of the levers of action to be undertaken. “This notion of sobriety concerns what individuals can change in their lifestyle, in different areas, in order to reduce their daily consumption. This can be done by limiting the use of electronic devices, transport, or even by changing one’s diet, with less meat, or more local consumption.”

“The IPCC report highlights two key points of attention: firstly, that sobriety cannot be focused on individual behaviour. Indeed, how can an individual be expected to become sober if the system in which he or she lives is not? Secondly, the report points out that efforts to reduce consumption, aiming at a sustainable and fair transition, will probably not be the same from one population to another: multiple factors, such as the level of wealth, must be taken into account.”

In general, the IPCC experts, and more broadly the academics who work on this notion of sobriety in various disciplines, point to the need for a structural and cultural change. “It is here”, she says, “that the social sciences have a very special role to play: the changes in behaviour and lifestyles highlighted in the report raise a sociological, ethical, political and even philosophical question for which it is difficult to envisage a universal and objective answer: what is just enough?”