EU-Mercosur agreement: sorting the true from false

- The EU-Mercosur free trade agreement has been fuelling public debate for several weeks now, with many declarations being made – some of which are inaccurate.

- Mercosur is negotiating a reduction in customs tariffs for a set quantity of products, fixed by quotas: relatively low for beef, but higher for poultry.

- The agreement with Mercosur does not provide for a reduction in European standards; the main issue is the effectiveness of border controls.

- In return for meat quotas, the export of European products such as wine, spirits and cheese to Mercosur countries has been negotiated.

- Deforestation in Latin America, caused by land exploitation, livestock farming and food production, remains a major problem linked to this agreement.

Although the trade agreement between the EU and Mercosur was signed on 6th December 2024, it still has to be ratified before it can be applied. As a result, the various points of the agreement are still being debated, and are even generating protests, especially from farmers in France.

A promise of prosperity for Europe, a sword of Damocles for French farmers, and a danger for the environment: the free trade agreement between the European Union (EU) and Mercosur has been shaking up public debate for several weeks now. With so much media coverage, several statements have been made about the agreement – some of which have been accurate, others less so, and the debate can only be clarified by examining them.

Charlotte Emlinger, an economist at the Centre d’études prospectives et d’informations internationales (CEPII), has widely shared her expertise on the Mercosur agreement in the media. On this occasion, she has often heard assertions which, although widespread, are not always accurate. With the help of Mathieu Parenti, professor at the Paris School of Economics (PSE) and researcher at INRAE, we have selected four that seem important to examine closely.

French agriculture is threatened by Mercosur’s low-cost products: False

“I often hear it said that the European market will be invaded by Mercosur products, but what is being negotiated are tariff quotas,” [Editor’s note: reduction in customs tariffs for a specific quantity per quota] says the economist. “The quantity of products that will be able to enter the European market with reduced customs duties is therefore limited.” For beef, this quota will potentially lead to an additional import of 99,000 tonnes per year. “This is a fairly small quota, which in the end represents just 1.2% of European consumption,” she adds. This addition, compared with the 200,000 tonnes already imported today, is unlikely to disrupt the European industry.

For poultry, on the other hand, the figures are higher: the quota will increase by 180,000 tonnes – representing 1.8% of annual European consumption – while current imports already stand at around 300,000 tonnes. Another key difference lies in the tariffs: the agreement provides for them to be completely abolished for the quantities of poultry negotiated, and for the beef quota to be increased to 5% – currently between 20% and 35%, depending on the product – which will logically reduce their market price.

However, the quotas negotiated include all types of cuts. We can therefore expect certain cuts, which Mercosur countries may specialise in, to account for a larger share of imports. “To be honest, the cuts that are most likely to be found on the European market will be quality cuts, with flagship products such as sirloin,” says Charlotte Emlinger. “At least, that will be the case for beef. For poultry, given the highly competitive nature of the Mercosur countries, the picture is likely to be different.” For this type of meat, the impact on the European market will therefore be more global.

What’s more, according to Mathieu Parenti: “It’s important to point out that the main competitors of French farmers are European farmers. But if we put aside European production and focus solely on imports, Mercosur is already exerting a significant influence on the market.” What remains problematic, from the point of view of unfair competition, is rather the European standards, both health and environmental, which make production more expensive. Because, as the professor points out, “as a general rule, the standards complied with by countries exporting to the EU are those relating to the finished product (such as maximum authorised pesticide residues), the idea being that these are the ones that can be detected in the EU. It is not by carrying out controls on the finished product that Europe will be able to control the production process. This is why the idea of introducing ‘mirror measures’, which would force production processes outside the EU to comply with the same standards as those on European soil (as in the case of hormone-treated beef), had been mooted. However, it remains difficult to implement.”

Agricultural products incompatible with European standards will reach the market: Uncertain

In reality, this statement is incorrect. However, the reality can sometimes be more nuanced. “The Mercosur agreement does not in any way provide for a reduction in European standards,” explains Charlotte Emlinger. “In other words, hormone-treated beef is banned in Europe, and will remain so despite the signing of this agreement. The issue is more about border controls than trade agreements.” As far as border controls are concerned, there are several possible arguments.

According to the CEPII economist, taking into account the number of tonnes of beef already exported today, increasing the quota should not upset the border control process. “Recent studies1 have shown that despite existing controls, products that do not meet border standards have found their way onto the European market,” she admits. “What’s more, some of the production standards required of European producers are not imposed at the border, nor could they be checked on entry to the European market. It is difficult to impose the same constraints on European farmers as on farmers in the rest of the world.”

Then there’s the difference already mentioned between the standards imposed on European farmers in terms of production and those that can be detected in the finished product. “It is not wrong to say that products incompatible with European production standards will be sold on the European market,” insists Mathieu Parenti. “We simply need to agree on the definition of standards. Standards that concern the finished product may be completely ineffective in regulating an externality generated upstream. There are a whole range of examples: the use of growth hormones and antibiotics in livestock farming (which require the development of separate sectors for the European market), deforestation (which requires the implementation of a traceability system), and so on. This is already the case with current imports. We know that despite the ban on certain pesticides in Europe, we import agricultural products from Mercosur, but also from the United States, grown with pesticides. In fact, Europe is in the process of changing its policy in this area, even if the results so far are rather disappointing2.”

To anticipate the impact of the Mercosur agreement, it is useful to look at similar cases that have already been negotiated. The CETA agreement, adopted in 2017, raised issues concerning the import of Canadian beef. This free trade agreement granted Canada a tariff quota of 53,000 tonnes of carcass equivalent (tce), effective from 2022. Canadian exports to Europe, however, amounted to just 1,519 tce in 20233. According to Charlotte Emlinger, who has worked on the subject, Canada “is not fulfilling its quota, because the ban on hormone-treated beef remains a major constraint.”

French agriculture loses out as a result of the agreements negotiated: False

All of which could point to this statement, making it all the more credible. In fact, Charlotte Emlinger would be more inclined to answer: “Not quite”, rather than “False”. “There are winners and losers within French agriculture itself, depending on the sector.” In fact, in return for these meat quotas, the Mercosur countries have been negotiated to open up to exports of other European products, such as wine, spirits and cheese.

In addition, this type of agreement includes lists of protected geographical indications, such as PDOs, to preserve French agriculture. “A Brazilian producer, for example, will no longer be able to sell cheese labelled as Comté, which can be done today,” she concedes. “One of our latest studies4 analysed the impact of the CETA agreement. As a result, our products have been able to sell at higher prices in Canada.” So even though part of European agriculture will be affected by the arrival of these products from Latin America, a whole range of producers could benefit.

This quid pro quo logic does not stop at agriculture. As the economist points out, “I often hear it said that that this agreement can be summed up simply as “Meat for Cars”. This is a bit simplistic, but it highlights the other side of the agreement, which seems to be more beneficial to the European Union.” Indeed, although the agricultural sector remains at the heart of concerns in France, other aspects of the agreement deserve attention.

The European automotive sector, for example, will see its trade with the Mercosur facilitated. The same applies to imports of the raw materials needed for the energy transition – notably in the manufacture of batteries – from Mercosur countries. This is an important point for European sovereignty in the face of future ecological challenges and China’s monopoly in this sector. However, it is uncertain whether the agreement is more beneficial for the European Union than for the Mercosur countries. And, according to Mathieu Parenti, “nobody really knows.”

This agreement risks increasing deforestation in South America: True

Deforestation in Latin America, and the Amazon in particular, remains a major problem. Increased international trade with this region will almost certainly result in increased production. “Taking beef as an example, it is logical to expect that opening up to the European market will increase production” explains Charlotte Emlinger. “The problem lies not only in the exploitation of the land required for this farming, but also in the production of the foodstuffs that feed it, such as soya.” Which, “even if we’re talking about small volumes, is likely to have an impact on the forests.”

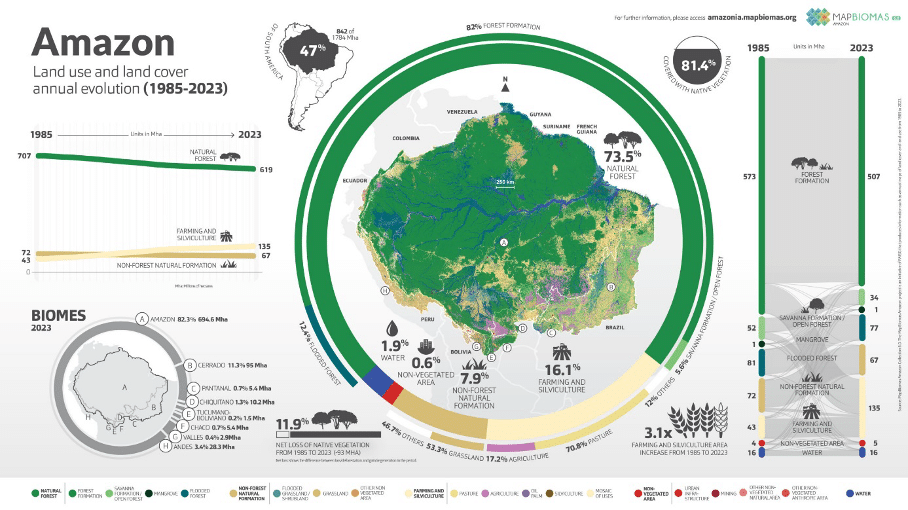

MapBiomas, a coalition of NGOs, condemns the major role played by agriculture in Amazon deforestation (see infographic). According to its studies5, the Amazon forest has lost almost 100 million hectares (Mha) since 1985 (707 Mha in 1985 to 619 Mha in 2023), and the area occupied by agriculture has increased 3.1 times over the same period (43 Mha in 1985 to 135 Mha in 2023). What’s more, although mining is also set to increase as a result of this agreement, its impact on deforestation appears to be minimal, although still present (5 Mha in 2023).

“The statement is far from false,” admits Mathieu Parenti. “Studies6 have shown that when anti-deforestation clauses are included in trade agreements, they tend to work well. However, the main effect was to limit the expansion of farms, and therefore impact on production. The problem is that with this type of clause, a rather perverse effect can emerge,” he adds. “To increase production, more intensive rather than more extensive farming will take place.” So, the other side of the coin will involve farming with far more soya or cattle per square metre – which could also have negative effects on the environment, such as increased methane emissions from cattle, soil pollution linked to soya production and a harmful impact on biodiversity.

According to France Info, one of the Élysée’s demands is to include a clause in the Paris climate agreement, failure to comply with which would lead to the suspension of the agreement with the Mercosur, in order to ensure sustainable development, limit deforestation and ensure compliance with health standards and controls7. For France, however, a clause strong enough to ensure compliance with these rules is not yet in place.