Addressing the water crisis is imperative for global climate adaptation. Current water policies focus primarily on visible, or « blue, » water sources, often overlooking the critical role of « green » water, stored in soil and vegetation, constituting about 60% of global land precipitation. Recognising water as a Global Common Good (GCG) is essential for achieving climate goals and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

At COP29, negotiations aim to achieve agreements to respond to the water crisis adequately; however, to do so, a proper understanding of the underlying hydrological cycle is necessary. The water, or hydrological cycle, is understood as “[…] a complex system with different stores interacting with varying strengths and over a wide range of scales with other components of the Earth system such as atmosphere, biosphere, and lithosphere1” and it is driven by solar radiation and gravity, with water changing into different states (liquid, gas, solid) and moving between the atmosphere, ocean and land. It evaporates and transpires from land and water bodies, then gets transported, condensed, and ultimately precipitates back onto the Earth’s surface.

Global water crisis

Worldwide, we are currently pushing the hydrological cycle out of balance. Through human-induced climate change, deforestation, and loss of biodiversity, we are changing precipitation patterns. As temperature rises, the cycle intensifies and evaporates more water leading to more extreme weather events, like extreme rainfall, hurricanes and coastal floods2.

Current water policies primarily focus on visible water sources, such as rivers and oceans (blue water), while frequently neglecting the importance of green water. Nonetheless, scientific evidence shows that around 60% of the precipitation that falls on land ends up stored as green water ‑further indicating that green water is the largest contributor to freshwater globally3. The importance of green water is further addressed by Friedlingstein et al4., who highlight that green water in soils is of necessity for land-based ecosystems, which can absorb 25–30% of carbon dioxide emitted from fossil fuels.

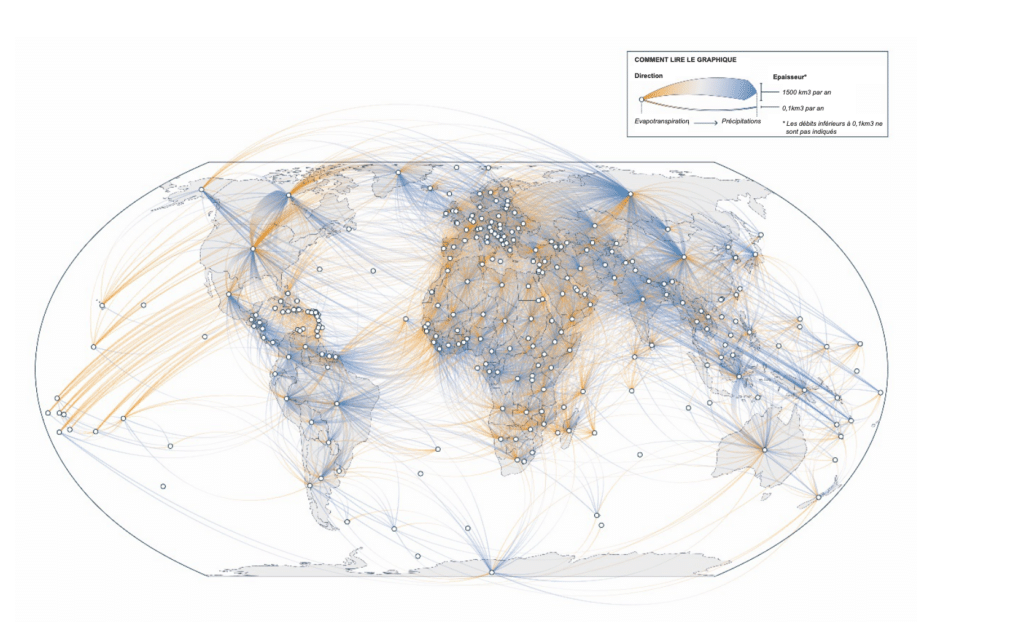

Figure 1 represents the global network of terrestrial moisture flows between different regions, showing how interconnected our world is via wind rivers. The arrows represent the direction of moisture flow, through two processes: evapotranspiration, the process where water is transferred from land to the atmosphere by evaporation and transpiration (from plants), and precipitation, moisture that returns to the land as rainfall. There are also points presenting the geographical centre of each country to demonstrate that water evapotranspires and precipitates from every country towards the rest of the world. Hence, the network showcases that countries are highly interconnected when it comes to moisture flows. This is scientific evidence that water evaporated from one region within a country can significantly impact rainfall in distant regions; countries are even more interconnected in terms of the hydrological cycle than previously thought.

Similar to river basins and aquifers, atmospheric moisture carries water from one country to another, across oceans and continents5, meaning that wind rivers can be tracked to demonstrate how economic activities taking place in one region or country can impact others downwind.

For example, water evaporation in West Africa is transported downwind to the Amazon Rainforest (mostly Brazil), where it arrives in the form of rainfall. Now, in the last decade, Brazil has promoted policies of heavy depletion of the Amazon Rainforest’s resources, which are leading to a loss of green water availability as the land’s capacity to store and use green water disappears. Hence, there is less green water that can be evaporated in the Amazon Rainforest to be transported further downwind to neighbouring countries. This is the case in countries such as Colombia, which rely heavily on rainfall water for consumption and energy production since resource depletion in Brazil has led to a lower water yield6.

Global interconnection in the water cycle is a fact, and it means we must start addressing the water crisis holistically where both green and blue water are at the forefront of global-scale policies and pacts.

Water as a Global Common Good

If water is part of this complex system called the hydrological ‑or water- cycle, governing it requires a shift in perception of the way it is conceived. Water must be increasingly understood as a Global Common Good (GCG). But what exactly does this concept entail?

First, recognising water as a GCC is acknowledging that communities, countries, and regions are interconnected, not only through visible water resources (blue water, such as rivers and lakes) but also through atmospheric moisture flows and green water (water stored in soil and vegetation). Second, this shift positions water high up in the international agenda since it understands that the Anthropocene’s impact on the hydrological cycle is intricately connected with the pressure it puts on other alarming processes such as climate change and biodiversity loss; for instance, a stable supply of green water is crucial for absorbing carbon dioxide and supporting ecosystems.

Moreover, this concept avoids treating water in a siloed manner when it comes to SDGs. The water crisis is not only an issue to solve via SDG 6 – which mostly deals with WASH (Water, sanitation and hygiene). Water is fundamental to achieving virtually all the SDGs since a destabilised hydrological cycle threatens food security, economic stability, public health, and social equity, which are cornerstones of sustainable development7.

The Global Water Pact

At COP29 in Baku, negotiators had a unique opportunity to promote an integrated approach to solve the water crisis and lay foundational steps towards a unified Global Water Pact by agreeing to the Baku Declaration on Water.

During November 19th (the day dedicated to food, agriculture, and water) key inputs were discussed for the Declaration. A crucial first outcome was the commitment to “[…] promote dialogue and partnerships [by] strengthening COP-to-COP synergies [and] supporting the development of collaborative and aligned climate action policy8”. This commitment is a milestone in establishing a Global Water Pact as it places the hydrological cycle as a whole at the heart of the Rio Trio – UNFCCC, UNCBD and UNCCD. After all, we know water security, conservation, and sustainable management must be treated integrally to achieve climate goals9.

The Declaration on Water, also framed water as a foundational element in climate action, as it asks countries to commit to “[…] effectively integrate water considerations in the design of climate policies, including national adaptation plans (NAPs) or strategies, nationally determined contributions (NDCs), and associated implementation plans, as well as national biodiversity strategies and action plans (NBSAPs) […]”. Now, the declaration was not explicit on the need to set clear global targets related to water conservation in its green and blue forms, limiting the support for international progress quantification policies, a crucial aspect for a well-designed Global Water Pact10.

Financial commitments were lacking on the Declaration on Water. For a Global Water Pact to become a reality, both, countries and financial institutions need to pledge investments in sustainable water infrastructure, innovative technologies, and conservation efforts, which the Declaration does not back. Additionally, the need for transparency and accountability around water and its resource-related uses (such as deforestation and energy production) was not explicitly stated. Hence, backing proposals such as the standardisation of data sharing process, green and blue water footprint disclosures, and sustainable corporate water practices, which facilitate businesses’ accountability in terms of impact to the hydrological cycle11 becomes harder.

A big win in terms of social inclusion was achieved on the Declaration on Water. The fifty signatory countries agreed to include the need to incorporate perspectives from often marginalised communities such as indigenous peoples, migrants and youth. A Global Water Pact will inherently need these voices to shape successful policies that protect local water resources in their blue and green forms and respect traditional knowledge since indigenous communities are stewards of natural resources, and young people are heirs of the consequences of today’s water policies12.

What’s next?

As scientific evidence proves that the hydrological cycle connects countries and regions far more deeply than previously thought, a Global Water Pact seems to be the most ambitious, yet crucial way to address the water crisis. COP29 had a key opportunity: to initiate a formal roadmap toward a Global Water Pact by outlining the role of water in climate action.

By no means is this declaration perfect: it does not promote a framework for water and climate finance, and it misses the chance of backing set goals for climate action. Yet, the Declaration also supports the need for COP-to-COP collaboration, promotes the integration of water – implicitly both blue and green – on national development plans, and calls for the voice of indigenous peoples and youth to be at the forefront of the debate. Overall, the Declaration on Water for Climate action signed at Baku during COP29 increases the momentum that water has gained in the past few years at the international scale and as UNCCD (the key COP for water action) approaches, the international community should follow closely the steps those countries will take to keep increasing water visibility on the international agenda.