Why do we want to reduce the impact of agriculture on the environment ?

Because this impact is major. The IPCC considers that, at global level, one third of greenhouse gas emissions come from agriculture. There is also a direct impact on biodiversity, through the transformation of habitats – this is of course a consequence of deforestation – the use of fertilisers and pesticides, the expansion of invasive species, and the withdrawal of biomass and water necessary for ecosystems. Agriculture is the human activity that has the greatest impact on biodiversity, leading to a serious phenomenon known as “defaunation”. The future of biodiversity depends to a large extent on the type of agriculture that is developed, and conversely, the future of agriculture depends on agricultural biodiversity. It should be remembered that every year, $235–577bn of agricultural production worldwide is at risk because of the disappearance of pollinators.

We often talk about the use of agro-ecology to limit the environmental impact of agriculture… But what is it ?

Agriculture has developed on the basis of an industrial model, with uniformity and standardisation of practices. But from a scientific point of view, this approach is ill-suited to the diversity of agricultural landscapes. You can’t grow maize and soya everywhere, or there will be serious environmental impacts ! Agricultural production is not diverse enough because some farms stick to very basic rotation systems, such as the maize/soya combination, whereas they should be made more complex, with legumes and longer rotations to maximise the synergies in each crop.

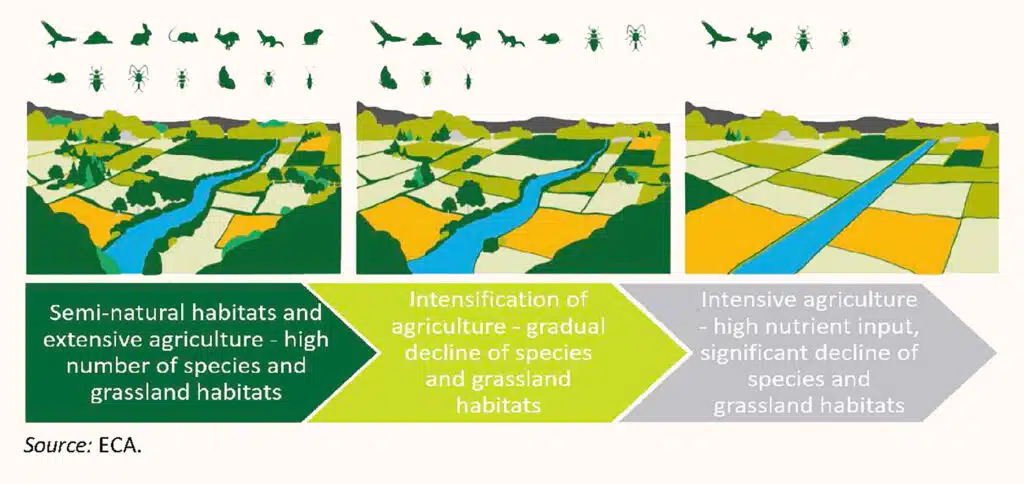

Agroecology is a model that takes into account ecological processes and biodiversity. It emphasises crop diversity and the importance of soil, fauna and flora biodiversity ; it integrates more ecological infrastructures such as hedges, thickets, and ponds. Hedges and thickets are home to birds, pollinators, and pest control species such as parasitoids and ground beetles. It is also necessary to reduce the size of the plots. The entire organisation of farms must therefore be reconsidered.

To do so, it is necessary to create relevant and ambitious financial and other incentives. We need to go further than the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP)2.

What about the soil ? Is it a question of cultivating it less ?

In reality, this is a complicated question, which is not scientifically clear-cut. Working the soil less deeply allows us to benefit more from the work of micro-organisms and earthworms. However, it can help with weed control and improve soil aeration… The balance between all these factors is therefore complex to find. But the stakes are high : soil degradation has reduced the productivity of the entire world’s land surface by 23%.

Agriculture is also being called upon to provide energy…

But the sustainability of this is being called into question. Producing additional crops for first-generation agrofuels (bioethanol, biodiesel) has many impacts on biodiversity. Making biofuels or biogas from waste also has its limits, as its availability is probably not that great. For example, there is little organic waste on a farm. Straw, for example, is used in animal husbandry or to regenerate the soil : it is a precious commodity ! Agriculture is thus essentially a recycling economy.

Soil degradation has reduced the productivity of the entire world’s land surface by 23%.

More and more farmers are investing in biomethanisers, installations that produce biogas from plant products or livestock manure. This is currently extremely profitable, as it is supported by subsidies. But is it really worthwhile from an ecological point of view, especially if crops are grown specifically to fuel them ?

But then, is agroecology also organic farming ? Sustainable agriculture ? Conservation agriculture ?

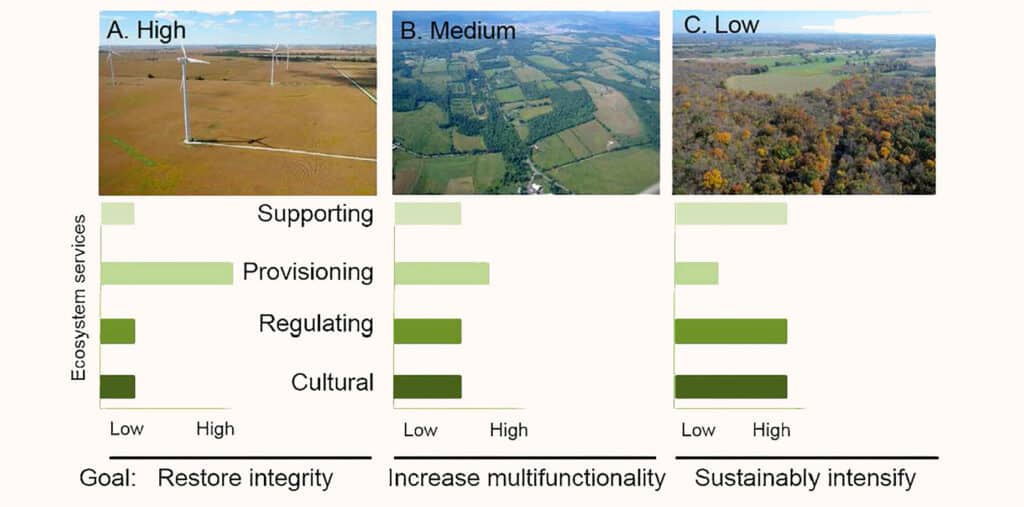

It is indeed an “umbrella : concept that covers all these practices and many others. It remains difficult to assess the advantages and disadvantages of each practice from a scientific point of view. They can all contribute to reducing the impact of agriculture on biodiversity. The European Academy of Sciences proposes yet another variant, “regenerative agriculture”.

These practices engage us as consumers but also as citizens. We need to ensure that our public policies support environmentally and socially relevant agricultural practices. But it isn’t easy ! Agroecology requires more work, and therefore more labour on the farm. This will inevitably have an impact on the price of products, which may be difficult for consumers to accept – political support is needed.

So political will is key. There is now talk of an agricultural Green Deal on a European scale, is this good news ?

This is a very relevant contribution produced by the Presidency of the European Union, while the CAP has just been reformed by the European Commission for the next five years… in a rather different vein from the Green Deal. So, we currently have two competing agricultural philosophies in Europe, which need to be reconciled.