10 years after the Paris Agreement, who are the G20’s “good performers”?

- This year marks the 10th anniversary of the Paris Agreement, an international treaty aimed at keeping global temperature rise below 2°C compared to pre-industrial levels.

- The average temperature over the last decade was already 1.1°C higher than in the pre-industrial period, and we are still far from meeting the mitigation targets.

- However, some countries stand out for their effective mitigation measures and have succeeded in reducing their greenhouse gas emissions.

- Ten G20 regions and nations have reached their peak emissions, an essential prerequisite for achieving carbon neutrality.

- Countries with particularly ambitious targets include the United Kingdom, South Africa and Chile.

This year marks the tenth anniversary of the Paris Agreement. This legally binding international treaty aims to keep the global average temperature rise well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels1. Ten years after its adoption, where do we stand? “There is evidence of progress, but the pace needs to increase significantly,” summarises Anna Pérez Català. Some countries are standing out with effective mitigation measures and have begun to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions, showing that it is possible to put humanity on the right track. The solutions are well known: develop renewable energy, electrify urban systems, improve energy efficiency and agricultural management, and reduce food waste2. It is essential to achieve carbon neutrality, i.e. to emit no more CO2 than carbon sinks are capable of absorbing.

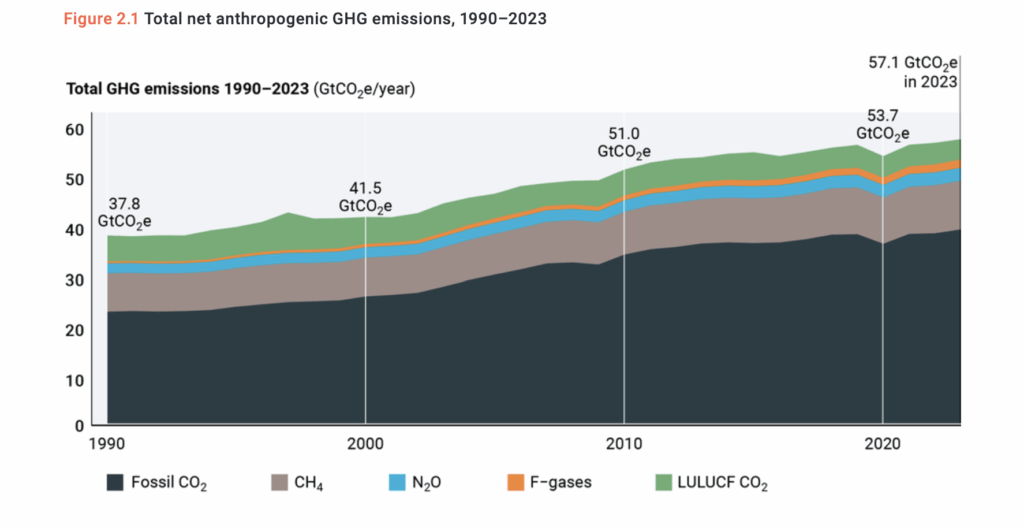

The average temperature over the last decade was already 1.1°C higher than in the pre-industrial period3. Make no mistake, while this article highlights some examples of countries that are doing well, the mitigation trajectory is still far from meeting the Paris Agreement targets. In 2023, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reached a new record high after years of growth: 57.1 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent (a unit that takes into account all GHGs4). Projections show that current policies are compatible with a warming of 2.7°C to 3.1°C by 2100, according to estimates5. In an optimistic scenario where countries deliver on all their promises (as stated in their nationally determined contributions and carbon neutrality commitments), warming would reach 1.9°C by the end of the century.

Positive signs of decarbonisation

There are positive signs. Ten G20 regions and nations have reached peak emissions, an essential prerequisite for achieving carbon neutrality (Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, the European Union, Japan, Russia, South Africa, the United Kingdom and the United States). A report published in 2021 highlights the importance of carbon neutrality as a driver of change7. According to the authors, “even if these changes do not necessarily translate into sufficiently ambitious emissions reductions, they help to gradually create the conditions for deep decarbonisation in the coming decades.” According to the United Nations Emission Gap Report, 107 countries – representing 82% of global GHG emissions – had adopted carbon neutrality commitments by September 2024. Five countries representing 0.1% of global emissions have achieved carbon neutrality (Bhutan, Comoros, Gabon, Guyana and Suriname8). According to the Climate Action Tracker updated in December 2023, only five regions and nations have adequately designed carbon neutrality targets: Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, the European Union and the United Kingdom9.

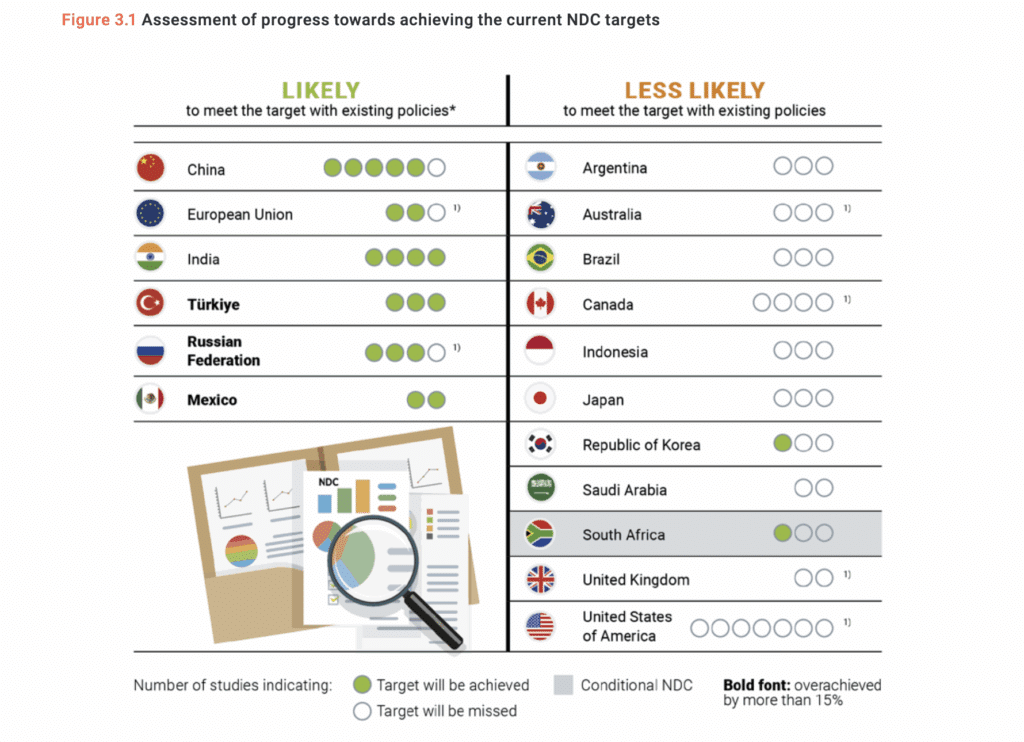

“When we look at societal changes or legislation, we see that a transition is underway,” says Anna Pérez Català. “Current measures are not enough, but the Paris Agreement provides for periodic reviews, which helps bring us closer to the long-term goals.” A central instrument of the Paris Agreement, nationally determined contributions (NDCs) are regularly updated. They reflect each country’s efforts to reduce GHG emissions. The latest review, expected in February 2025, is still ongoing for many countries. However, there remains a gap between ambition and reality. Among the G20 countries, 11 would not be able to achieve their NDC targets with current policies. Several G20 members could achieve their targets, but these have not been scaled up, or have been scaled up only marginally, since the Paris Agreement.

Countries with ambitious goals to combat global warming

Is it possible to identify the best performers? “No country is perfect, but according to the indicators observed, some countries are showing significant ambition,” replies Anna Pérez Català. She continues: “One example is the United Kingdom, which has produced an impressive updated NDC, aligned with the scientific objectives and the goal of limiting global warming to 1.5°C. South Africa also prioritises climate issues, with a dedicated presidential commission. Chile stands out for calculating emissions reductions in absolute rather than relative terms. It is essential to consider different indicators to determine whether a country is on track.”

As the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases, energy is one of these important indicators. Fossil fuels are still the main source of global energy, but their share is declining as solar and wind power generation increases. Emissions from the energy sector could soon peak. The United Kingdom is one of the countries leading the way with a rapid energy transition. It was one of the first to legislate in favour of a long-term GHG emission reduction target for the entire economy. All coal-fired power stations have been closed, and renewable energies have been deployed on a massive scale, particularly offshore wind farms. Between the early 2000s and 2023, the country’s CO2 emissions fell from around 570 megatonnes per year to 305 megatonnes. Scotland, Austria, Denmark and California also aim to generate 100% of their electricity from renewables.

“It is also important to ensure a fair and equitable transition, otherwise there is a risk of generating resistance, as is currently the case with boilers in Germany and electric cars in France,” adds Anna Pérez Català. It is difficult to provide a miracle solution for the transition, as mitigation strategies differ from one region to another. But there are certainly examples of success that can be replicated. “For example, Spain has achieved a socially just phase-out of coal by training and re-employing former miners in other sectors of the local economy,” explains Anna Pérez Català. “This requires significant planning and investment, but it is necessary to ensure fair transitions.”

While economic growth remains a goal for many countries, the IPCC noted in 2022 that 43 out of 166 countries managed to stabilise or reduce their GHG emissions while increasing their GDP between 2010 and 201511. “A group of developed countries, such as some EU countries and the United States, and some developing countries, such as Cuba, have achieved a complete decoupling of consumption-based CO2 emissions and GDP growth,” the IPCC continues. “Once again, a just transition that incorporates long-term strategies is crucial to successful mitigation,” concludes Anna Pérez Català. “Geopolitical challenges such as wars and political changes are hindering cooperation, but we have high hopes for the next COP in Brazil, whose diplomatic skills could positively influence the outcome.”