Within the energy sector, heating is and will remain a major part of the energy consumption (about half of the energy demand in buildings). District heating could be a great vector of the energy transition as it is a way of integrating clean energy on a large-scale. However, this potential remains very much under-exploited as 90 % of the heat supplied through networks is still fossil-based (75 % in Europe, the more adanced continent when it comes to the integration of renewable energy in district heating systems), and only 9 % of the global heating demand (industrial and buildings) is provided through district heating.

#1 District heating already exists in many locations

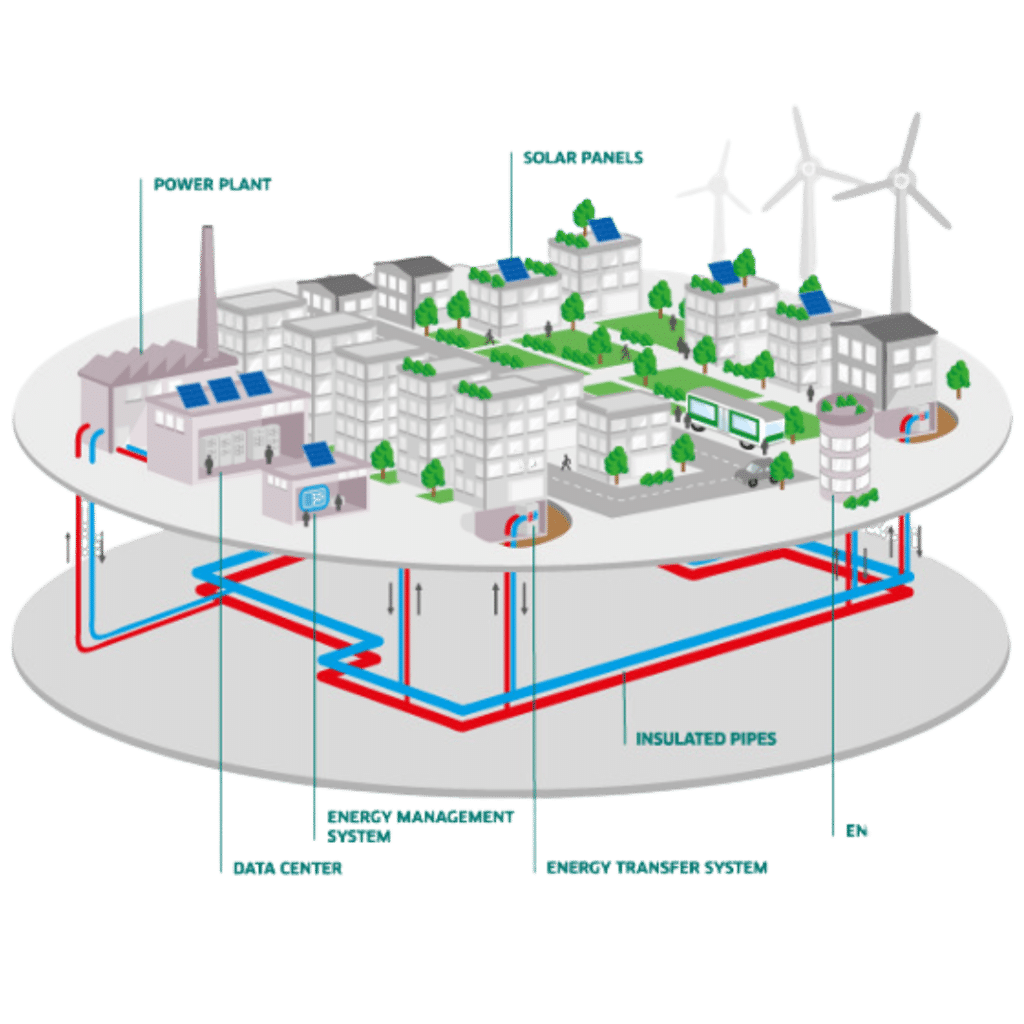

District heating is a collective heat distribution system. In France, it usually also encompasses the production plants. In the heat plants, a fluid – steam or water – is heated by incineration heat, biomass boilers, or geothermal energy. This hot fluid is then transported through insulated pipes to sub-stations, connecting the district heating system to secondary systems. The secondary system corresponds to the distribution system inside buildings – for instance, the pipes running through buildings from the substation to the radiators. This secondary system is distinct from district heating and is not regulated under the same contract. The type of buildings supplied by district heating can vary from country to country.

In most cases, district heating is developed in areas where there are already buildings consuming much heat, such as hospitals, malls, office buildings, or social housing. Private housing like collective housing or individual housing can also be connected to the system, but not in every country. In France, the oldest district heating systems date back from before the 1950s in some major cities like Paris, Strasbourg or Grenoble1. For instance, Paris had its district heating in 1927. It is still under operation and works with steam. From the 1950s to the 1970s, district heating systems were developed in many cities but mainly restricted to new neighbourhood or around incineration plants to use the heat. In the 1980s, the oil crisis led to the development of geothermal based district heating, like in the Parisian region. However, these systems quickly became economically unviable due to the competition with gas.

District heating, as an energy utility, is a public service. The local public authority owns the system and is responsible for its operation. In France, operation and maintenance are often delegated to a private operator through a Public Service Delegation. These contracts can last for decades (usually about 25 years), and the private operator bears the investments2. However, more and more local public authorities are considering their district heating system as a great lever for the ecological transition.

#2 District heating systems are beneficial for the ecological transition

Heating and cooling accounts for roughly half of the energy consumed in the European Union3 but currently dominated by fossil fuels4. District heating could support large-scale sustainable heat production. Indeed, instead of asking thousands of families to change their old fuel boiler, the whole neighbourhood can move from fossil fuels to sustainable energy by changing the fuel-based production plant to, for instance, a biomass-based one. Moreover, by lowering the fluid temperature and adding thermal storages, it is easier to integrate a greater variety of local and sustainable production means: industrial waste heat, shallow geothermal energy, large-scale heat pumps, etc. District heating is also a great teammate: it can be coupled with a cooling system or be used as a way of storing renewable electricity production.

By integrating a variety of local resources, district heating is a great lever for many local transitions. It is a lever for local public authorities to act on decarbonisation, air pollution, energy poverty, etc. It can even become an object of local democracy if citizens are integrated to its planning and governance. It can also promote local energy sovereignty by securing a local energy supply and reduce energy dependence. For instance, Dunkirk is the biggest French district heating system based on industrial heat recovery. Since the oil crisis, the municipality wanted to have more energy sovereignty and be able to control the prices of heat. They developed in 1986 a district heating recovering waste heat from Arcelor-Mittal, a major steel manufacturer. Thanks to this recuperation, Arcelor-Mittal has to burn less of its remaining gas, improving both the air quality and the local attractivity.

In 2009, the Heat Funds, a French public subsidy supporting the development of renewable heat was set up. It aims at making renewable and recovered heat competitive with gas-based solutions. It participated to securing the remaining geothermal-based district heating and helped the development of new ones, based on at least 50 % of renewable or recovered heat. Thanks to this new dynamic, France has now 898 district heating systems in operation, with 62.6 % of renewable or recovered heat production in average5.

#3 The potential of district heating is greater than its current visibility

You have probably already heard about green electricity with wind turbines or solar panels. You have probably heard about biogas, green gases, and hydrogen. But had you heard about sustainable district heating systems? Can you name one company providing district heating?

District heating is under-represented in the energy sector, and not a lot of institutions are solely advocating for these systems in a visible way. The major European network promoting district heating is named Euroheat&Power… a name giving no explicit indication on its focus towards district energy. Many French companies providing district heating are also major actors of the electricity and gas markets, which can lead to internal interest conflicts. Moreover, some countries – like France – had historically made the political choice to nationally develop the gas and electricity networks.

District heating is under-represented in the energy sector, and not a lot of institutions are solely advocating for these systems in a visible way.

With these two utilities in place and the under-representation of district heating, it can be hard for local public authorities to 1) gain knowledge about district heating, 2) justify the development of a new energy utility when two are already fully operational and able to provide heat. To add to the second point, a district heating system needs a high level of heat demand and density to be economically viable. In places where there is no mandatory connection to the system, it can be hard to achieve and secure this level of demand. Indeed, there are a lot of solutions – sustainable or not – to be provided with heating and hot water: individual gas or fuel boilers, electrical heating, individual heat pump, solar thermal panels, etc. Some of these solutions are also supported by public policies, like the setting up of individual heat pumps or electrical heating – a very inefficient heating means, but quite developed in France due to the low price of electricity and the policies supporting nuclear-based electricity.

Two things make it even harder for district heating to be visible. First, its invisibility! The whole system runs underground, and heat is not as visible in our landscapes as electricity. The only visible parts are plants, which can lead to a rather unpopular opinion on district heating… Second, the disconnection to final users. As mentioned earlier, district heating is distinct from the secondary system. The customers are the building owners, not the final users, and there is no direct link between heat users and district heating actors. Many customers do not even know that they are provided heat through district heating!