Freight: why trains haven’t (yet) replaced lorries

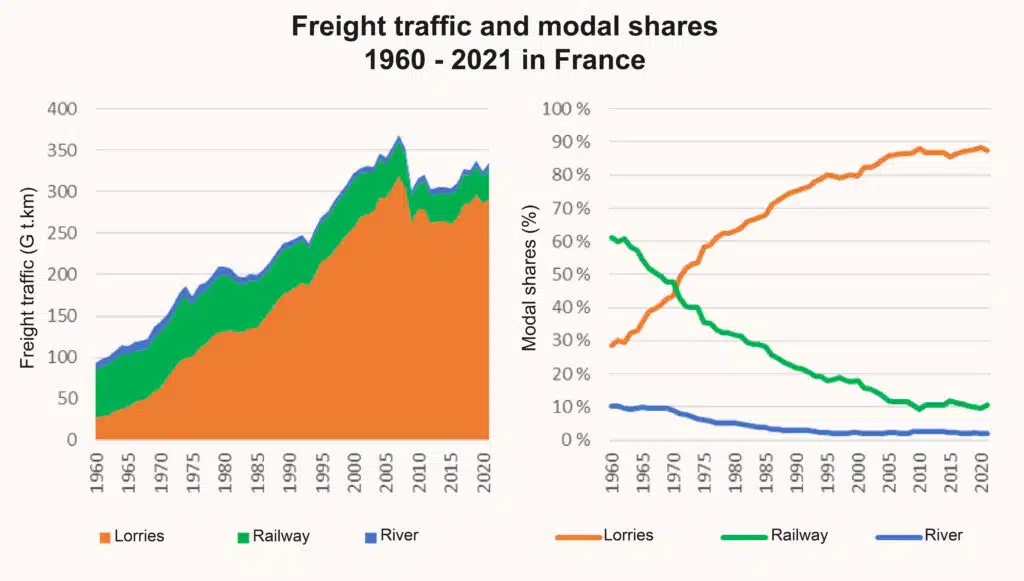

- In France, since the mid-2000s, road transport has accounted for 88% of freight flows, compared with 10% for rail and 2% for waterways.

- Rail transport is the main opportunity to reduce CO2 emissions from domestic freight in France.

- However, France is struggling to catch up, while the modal share of rail is almost twice as high (18%) across the EU or in Germany.

- Public policies remain insufficient, as shown by the 2021 plan to revive rail freight, which will not achieve its objectives.

- This plan forgets three elements: considering the future demand for freight transport; the decrease in road traffic; the evolution of our economy and logistics.

Everyone agrees on the principle. Transporting our goods by train rather than in lorries is a lever to be used for the environmental transition. In addition to reducing CO2 emissions, it reduces road traffic, congestion and space consumption, road accidents and damage to road infrastructure.

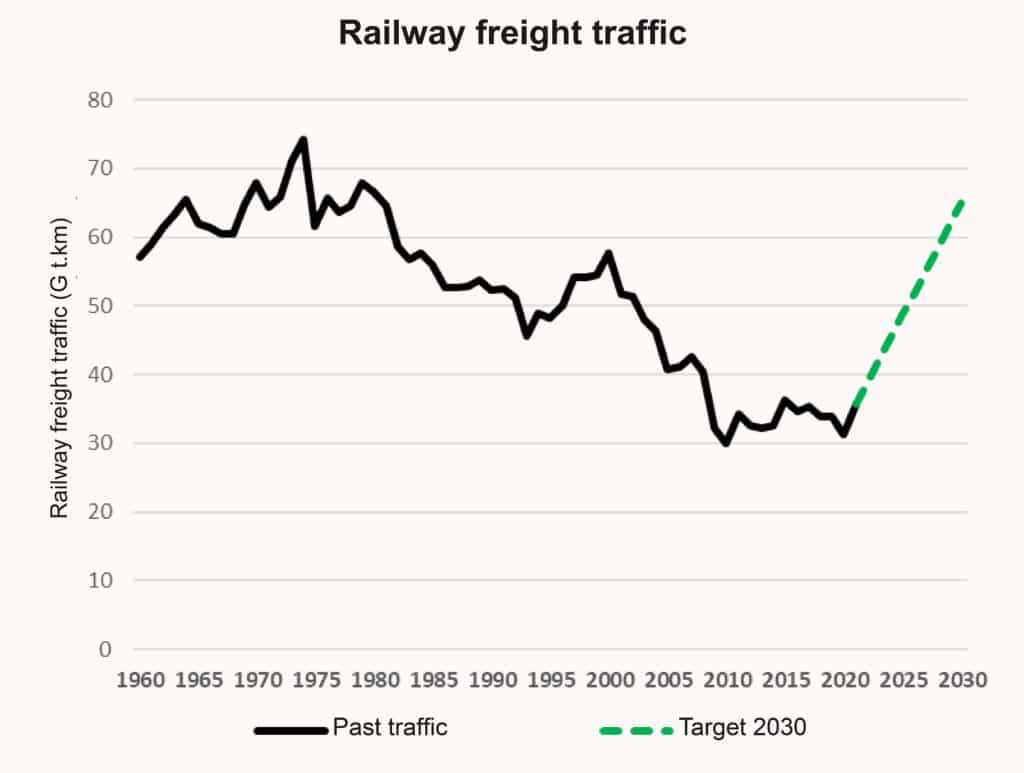

And yet, for decades now, there has been a succession of plans to revive rail freight, and their targets have been missed with a stable share of rail freight, but this has not prevented the announcement of objectives that are increasingly ambitious. The latest target set in 2021 is to double the modal share of rail freight by 2030. Several questions arise. Where do past failures come from? Is it likely to work this time? What should be integrated into public thinking and policies?

For a century, a massive modal shift towards road transport

In France, rail freight transport started about two centuries ago. The first line in France was opened in 1827 and was initially designed to transport coal between Saint-Étienne and Andrézieux, with wagons pulled by horses or descending the slope by gravity. At that time, road transport dominated, ahead of river transport. Then rail transport grew enormously, accounting for almost 80% of traffic in France at the beginning of the 20th Century, relegating road traffic to only 10% of the modal share1.

Since the mid-2000s, road transport has accounted for 88% of freight flows in France, while rail has stagnated at 10% of traffic, leaving a small 2% for river freight2.

Many attempts have been made to revive the railways. For example, in 2000, the SNCF aimed to double rail traffic by 20103. The result? Between 2000 and 2010, rail freight traffic was… divided by 2. There are many reasons to explain the decline of rail and the failures of past modal shift policies: the lack of investment in infrastructure, insufficient quality of service4, the gradual abandonment of certain activities (such as single wagonloads), the de-industrialisation of France, and the lack of dynamism of French ports (and their poor rail connections)5.

But the reasons are also to be found in the incredible growth of road transport. The entire organisation of logistics and the economy has been built around heavy goods vehicles. Thus, if the modal share of rail has fallen from around 60% to 10% since 1960, it is certainly because rail traffic has fallen by 37%, but also and above all because total demand has increased 3.6 times over the period, driven by an approximately tenfold increase in road traffic.

This has relegated rail freight to its main area of relevance: mass transport, generally over long distances and for large volumes, for which road transport is becoming less efficient and more expensive. This is reflected in the dynamism of combined road-rail transport in recent years, with the opening of several rail highways, allowing semi-trailers to cross France on adapted trains6.

France is also a poor performer compared to its European neighbours, showing the room for manoeuvre that exists in France. The modal share of rail is almost twice as high on average in the EU or in neighbouring Germany (both at 18%). And the decline in rail traffic in France over the last few decades contrasts with more dynamic developments in other European countries7.

Doubling the share of rail by 2030, under what conditions?

In a plan to revive rail freight, the most obvious aim is to improve the supply of rail freight. The 2021 plan is thus based on 72 measures, grouped into three areas: making rail freight an attractive, reliable, and competitive mode of transport; acting on all the growth potential of rail freight; and supporting the modernisation and development of the network8.

While essential (and without even going into the details and possible shortcomings here9), this support for rail is and will be insufficient to achieve the objectives, given that too little account is taken of the following three elements.

What (de)growth in demand will there be in the future?

The first element is to know what the evolution of total demand for freight transport will be by 2030, and thus what increase in rail traffic will be necessary to achieve a doubling of the modal share.

This projection is not clearly defined in the recovery plan, but the figures mentioned seem to foresee an increase close to +10% in total demand by 2030. In such a context, rail traffic would have to increase by 120% to double its modal share. Rail would thus absorb the increase in freight traffic, without really reducing road traffic.

On the contrary, in a scenario of strong sobriety on an economy-wide scale, transport demand could be reduced by 20% by 203010. In this case, it would be “sufficient” to increase rail traffic by 60% (an increase half that of the previous case!) to double the modal share of rail. And in this case, road transport traffic would fall by 30%, under the dual effect of the fall in total demand and the increase in the rail share.

The evolution of total demand [the subject of a forthcoming article, the last in the series] is therefore fundamental in the sizing of rail traffic to achieve the objective. Past experience shows that the share of rail has evolved more as a result of this evolution in total demand than in rail traffic. This evolution is also fundamental to reduce road traffic and thus have a downward effect on emissions, which is in line with the following point.

Reducing the share of road transport, an unassumed objective

Another shortcoming of this objective of doubling the modal share of rail is an implicit assumption that is not clearly made. If the share of rail increases by 9% to 18%, this will be at the expense of road transport, whose share will have to fall by 9%11. To go even further, to reduce emissions, the objective is not to increase rail freight, but to reduce road traffic.

However, the objective is never presented in this form, and policies are not oriented in this direction. For example, neither this plan nor other policies on freight transport have provided for major changes in road infrastructure charging (following the abandonment of the ecotax in 2013–2014), the end of the partial reimbursement of energy taxes for road transport, the reduction in the speed of heavy goods vehicles or even modal shift obligations12.

Today, the predominance of road transport can nevertheless be explained by undeniable advantages compared to rail: “Roads offer flexibility, speed, reliability, low prices, and availability of capacity”, as the president of the Freight Transport Users’ Association13 summarises. In such a context, it is quite illusory to be able to reduce the share of road transport by 9% only by investing in rail, and without discouraging the use of road transport.

What changes in the territory, the economy and logistics?

In view of its ambition, doubling the share of rail transport must finally be part of a wider evolution of the economy and logistics. First of all, it is a question of making land-use planning policies consistent, while motorway projects are still underway and logistics warehouses continue to be built on the outskirts of towns without being connected to the railways. This maintains and even strengthens the current dependence on road transport. The possibilities of shifting to rail will also depend on changes in the types of goods transported and over what distances. This raises questions about industrial policy, the transition of the agri-food or construction sectors, which account for a large proportion of freight traffic in France14.

Finally, in view of the constraints inherent in rail, the logistics organisation must also change to make more use of the train. In particular, it is a question of loosening time constraints, avoiding just-in-time and tight logistics chains, and instead managing stocks in order to massify transport flows. This is, for example, contrary to the current trend towards the growth of e‑commerce and rapid delivery, which are structurally unfavourable to rail and for which there is a lack of regulation15.

Other modal shift opportunities

Rail transport is the main opportunity for modal shift to reduce CO2 emissions from domestic freight in France. But other possibilities exist in the global, national and local logistics segments.

On an intercontinental scale, maritime transport should be prioritised as much as possible over air freight, which emits around 100 times more CO2 per tonne transported16. Given its much higher cost, air transport is used more for high value-added products or when time is of the essence, such as for perishable foodstuffs. Increasingly, e‑commerce players are also investing in air freight for fast deliveries, a trend that should be limited.

For national transport and in addition to rail freight, modal shift is also possible via river transport. Its development is essentially limited by geographical constraints and by the available waterways, which explain its current modal share of 2%. There is, however, potential for development and transfer from road transport on major routes, inter-basin links or for delivery in the centre of conurbations connected to a navigable river17. Finally, for last-mile delivery, cargo bikes can replace a large proportion of light commercial vehicles. Per unit transported, the climatic benefit of this transfer is very high, especially if the deliveries were previously rapid and not very optimised and made by combustion engines. However, overall, the gain in freight transport emissions is limited, as the demand that can be addressed remains limited (distances and volumes being relatively small for cargo bikes). More significant benefits will be felt in terms of reducing air pollution, space consumption, resources, noise and danger to other users.

Conclusion

The modal shift objectives have certainly been too ambitious in relation to the transformation efforts required to achieve them and the inertia that exists in freight transport. However, breakthroughs are necessary to achieve the decarbonisation objectives, justifying ambitious modal shift objectives. Public policies have been and still are far from committing to strong shifts, both because of insufficient support for rail transport, in terms of investment or support for activity. But also, and above all, because the supply (or support) policy for rail is insufficient to seriously challenge the current hegemony of road transport18. Yet it is almost exclusively with this bias that modal shift policy is still considered in France, despite the failures of past policies.