Electric vehicles: Europe is chasing lithium closer to home

- The EU ban on new combustion-powered cars is driving the European automotive industry towards electric vehicles, with expected growth of 10% per year until 2028.

- But Europe is not competitive in this industry and will be dependent on China for the raw materials and refineries needed to make batteries.

- To achieve its objectives, the EU will have to sign bilateral agreements with countries that have abundant, lower-cost lithium to position itself strategically in the battery value chain.

- It is above all by strengthening the recycling capabilities (for cars and their components) that Europe will be able to make its mark.

- The EU's future objectives are clear: security of supply and energy transition.

The EU ban on the sale of new combustion engine cars from 2035 is shifting the European car industry towards the most competitive existing alternative: the electric car. By 2028, we expect the global market for electric cars to grow by almost 10% a year. In automotive terms, the European industry has historically been competitive, but it is no longer so when it comes to electric cars. This industry is dominated by the Chinese company BYD, and Tesla in the United States (respectively 17.5% and 12.5% of the market in 2023).

The defining component of electric cars is the battery. To conquer the battery market, Europe has decided to invest in so-called gigafactories. In October 2023, for example, the European Investment Bank announced that it would be investing €450m from 2025 onwards. These giant factories, dedicated to battery design, are only competitive if sourcing of the necessary raw materials is available. Yet, to achieve the 2035 target, both the raw materials and refining markets need to be properly assessed.

Electric vehicles and batteries: a market in several stages

To position itself in the electric car market, Europe will have to invest in the whole battery supply chain. From an economic point of view, there are several stages in the battery value chain that need to be addressed.

The upstream market covers the extraction of resources. The “midstream” market covers the transformation stage, i.e. the refining of these resources. The downstream market ranges from anode/cathode production to cell production and the final assembly of batteries in gigafactories.

Mining is relatively evenly divided between several companies. However, extraction oligopolies still exist for some materials. The Chilean company SQM and the American Albermarle had the largest market share in 2022 (20% and 16% respectively).

It is at the refining stage that the first warning signs appear: more than 40% of the lithium found in batteries is refined in China, by Chinese companies. The rate rises to 65% for nickel and 93% for manganese1. The same applies to the manufacture of anode and cathode components, more than 50% of which are produced in China. For batteries, and more generally for electric cars, Europe is dependent on Chinese production.

The downstream market and its gigafactories

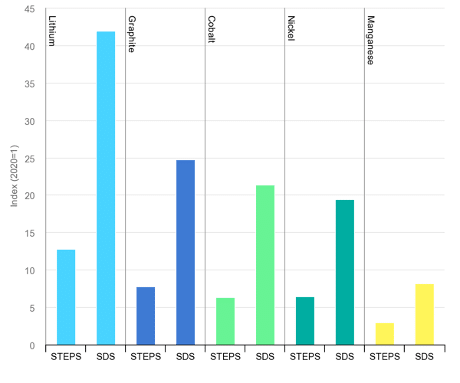

Europe has not invested enough in the “upper end” of the battery value chain. As a result, the supply of electric cars will not be able to keep pace with European demand. For example, demand for lithium will increase 40-fold by 2040. But supply is not keeping pace, given the time needed to open mines and refineries. The trends are similar for other battery components, such as cobalt and nickel.

How can we meet the challenge of 2035?

China refines over 40% of the lithium that will end up in our batteries, although it only extracts 13.36%.The challenge is not so much in extracting raw materials, but in strategic positioning the EU at the intermediate stages of the battery value chain. Europe should first try to sign bilateral agreements with countries that have abundant, cheaper lithium. It would also be in Europe’s interests to develop the industry locally. Finally, Europe should invest in refining and the manufacture of components.

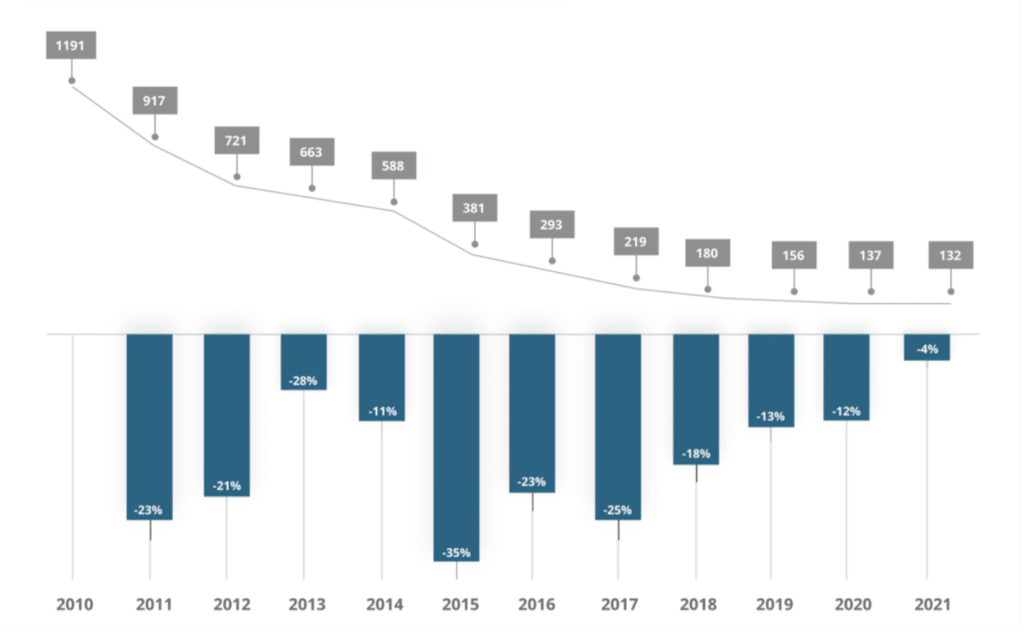

Finally, the development of a recycling industry for batteries and their components is a lever that has not been mentioned enough but is nonetheless very important. This sector is not yet sufficiently developed anywhere. Mastering the recycling of cars and their components could be Europe’s competitive advantage. For greater efficiency, and to limit the costs of these investments, these efforts should not be spread too thinly. With a strong Europe-wide policy, rather than a case-by-case policy, scale economies would be substantial. Learning effects are the reason why we are already seeing a reduction in battery production costs. Additionally, such an effort would have spill-over effects on other sectors and other technologies.

At present, fossil fuels are expensive, and they will remain so. Europe must therefore prepare for this future. Yet most of our greenhouse gas emissions come from the use of fossil fuels. The objectives of energy security and energy transition are therefore closely aligned. Hence the need to invest in raw materials that are critical to the transition. At the same time, Europe must set itself the goal of becoming a pioneer in the circular economy, battery recycling and energy efficiency. That is the challenge for the next decade.