Which viruses are the most dangerous ?

- Several criteria need to be considered to determine how dangerous a virus is, including its lethality, the number of people infected and its mode of transmission.

- How dangerous a virus is also depends on the long-term after-effects it leaves behind, such as Lassa fever, which causes deafness and myocarditis.

- Until it was eradicated in 1979, smallpox was probably the worst pandemic, with a mortality rate of 30% and 300 million victims over the last century.

- The Covid-19 pandemic may have caused more than 18 million deaths in just two years, around thirteen times more than HIV over the same period.

- Vaccines and treatments can considerably reduce the lethality of various viruses, but their availability remains extremely unequal around the world.

They have shaped our evolution and can be promising medical tools, but viruses are above all associated with the notion of disease. They even take their name from the Latin word for poison… Let’s take a look at the most dangerous specimens in the viral menagerie.

The most deadly viruses

The first thing that comes to mind when we talk about how dangerous a virus is generally its lethality : if a person is infected, what is the risk of them dying ? Some viruses are particularly worrying from this point of view. The rabies virus, which affects the nervous system, is almost 100% fatal once symptoms appear. The best defense against this disease is vaccination. Useful before or after exposure to the virus, it can be used in humans but also in animals likely to contaminate them, mainly domestic dogs1.

HIV, the Human Immunodeficiency Virus, is also fatal in almost 100% of cases if left untreated. Less than one percent of patients seem to be able to spontaneously control the virus and avoid the development of Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS)2. Fortunately, current treatments can control HIV so effectively that infected people may no longer have symptoms, no longer be contagious and no longer die because of the viral infection. Despite the absence of a vaccine, effective preventive approaches do exist, notably pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PreP. However, access to these therapies remains unequal across the world, and there is no treatment that can be used on a large scale to cure HIV.

The examples of rabies and HIV show that the intrinsic lethality of a virus can be greatly reduced when effective means of prevention or treatment are available. Progress is being made in these areas with another type of particularly lethal virus : filoviruses. This is the family of viruses that includes Ebola and Marburg, which do not cause disease in some African bats but do cause hemorrhagic fevers in humans. The average fatality rate is around 50%, but varies according to epidemic and strain, and has already exceeded 80%3. The WHO now recommends two monoclonal antibody-based treatments for the most dangerous strain of Ebola4, as well as two vaccines, although research is still underway to determine the best vaccine regimens5.

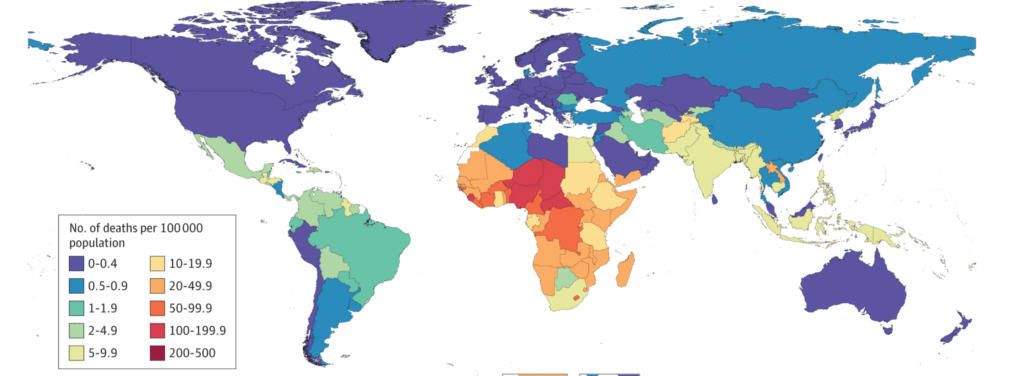

We can reduce lethality of various viruses thanks to vaccines and treatments. But we must not forget that they are extremely unevenly available around the world, and vary according to geographical area, geopolitical situation, or financial resources. Not all populations have the same opportunities when faced with the same infectious agent6.

From theoretical lethality to actual mortality

Some viruses become particularly dangerous when they trigger specific diseases : the severe form of yellow fever or the pulmonary syndrome caused by certain Hantaviruses, transmitted by rodents7, can exceed 50% lethality. Fortunately, however, these clinical forms are relatively rare. This illustrates another parameter to be considered when assessing the danger of a virus : the number of people it infects and makes ill. The Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus, transmitted by ticks, is a cause for concern, with a fatality rate of around 40%. It is therefore being monitored and studied, but although it has been present for decades and is endemic in some countries, fewer than 20,000 cases have been recorded in total8.

To assess the real impact of a virus, it seems relevant to look at the number of deaths it has actually caused. From this point of view, HIV, with its 40 million deaths over forty years, remains the main scourge of the present day, but SARS-CoV‑2 has affected so many people and had so many indirect impacts that the Covid-19 pandemic may have caused more than 18 million deaths in just two years, i.e. around thirteen times more than HIV over the same period9. This considerable number is still lower than the consequences of the Spanish flu, which is thought to have claimed at least 50 million lives in 1918 and 1919, in a context complicated by the First World War10. This pandemic is considered to be one of the worst ever experienced by humanity.

However, the further back we go, the more difficult it is to make estimates, and comparisons lose their relevance if we don’t consider the increase in the number of humans living together on our planet. If we exclude plagues caused by bacteria, the worst pandemic is probably that caused by smallpox. With a mortality rate of around 30%, major after-effects in some of the survivors, thousands of years of propagation and 300 million victims in the twentieth century alone, it’s enough to make you shudder12. This disease, brought to America by the conquistadors, is even thought to have played a fundamental role in the conquest of the New World, because the native population had no immunity at all13. But smallpox is also one of humanity’s greatest successes : since 1979, it is the only human disease to have been officially eradicated thanks to vaccination.

Different reasons for concern

The mortality rate of a virus is inevitably a significant factor, but it is far from the only parameter to be taken into account when assessing how dangerous it is. For example, the impact may be considered more serious when it affects certain populations, such as children. Rotaviruses, for example, do not appear to pose much of a threat if they are presented as the cause of gastro-enteritis. But they particularly affect children under the age of five, in whom they can cause severe dehydration leading to hospitalisation. More than 180,000 children died from them in 2017, mainly in low- and middle-income countries14.

Furthermore, how dangerous a virus is depends very much on its rate and modes of transmission. Measles is particularly impressive in this respect : one infected person can infect around fifteen others, making this disease very difficult to control. It is so contagious that its spread can only be stopped if 95% of the population is immunised. However, vaccination coverage is far from reaching this level everywhere in the world, including Europe15. As a result, no country has managed to rid itself of this deadly disease, which remains a cause for concern for health agencies16.

The three coronaviruses that have caused problems over the last twenty years illustrate the importance of contagiousness in the danger posed by a virus. MERS-CoV, which appeared in Saudi Arabia in 2012, seems worrying with its case-fatality rate of around 35%, but it has caused fewer than 1,000 deaths in total because it is very difficult to transmit between humans : most cases result from contact with dromedaries carrying the virus18. Conversely, SARS-CoV‑2 has a fairly low case-fatality rate (which is difficult to estimate at the moment because it varies depending on the variant, age, level of immunisation, etc.), but it has caused many more deaths because it has infected more people.

For its part, SARS-CoV‑1, which appeared in 2002 and was responsible for SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome), was as contagious as SARS-CoV‑2 at the start of the pandemic, and had similar modes of transmission. However, this virus, which is lethal in almost 10% of cases, was stopped in just a few months, whereas its more recent cousin became uncontrollable… Because carriers of SARS-CoV‑1 were only contagious when they were symptomatic. It was therefore easy to set up effective quarantines. SARS-CoV‑2, on the other hand, can be transmitted by people who show no symptoms, making it much more difficult to stop. The contagiousness of asymptomatic people is therefore also a danger factor. It also partly explains the spread of HIV, where carriers can be contaminated for up to ten years before developing symptoms.

More than just deaths

Finally, to assess how dangerous a virus is, we need to consider all its consequences, which, as the Covid-19 pandemic clearly showed, are not limited to mortality. Hospitalisation, which can overwhelm a healthcare system, and long-term after-effects, which have health implications as well as social and economic ones, can also be significant. This was the case with smallpox, which caused scars, particularly on the face, but could also lead to blindness. Polio, which has almost disappeared thanks to vaccination but is still circulating in Pakistan and Afghanistan, can cause permanent paralysis19. And Lassa fever, endemic in West Africa, causes deafness and myocarditis20.

Papillomaviruses can cause cancer not only of the cervix, but also of the vagina, vulva, anus, penis and oral cavity. Vaccination against certain strains can now drastically reduce these risks.

The list of viruses whose consequences persist over time is a long one : we could add to it those that promote the development of cancers, such as papillomaviruses or hepatitis B and C viruses21, those likely to cause more severe symptoms when reactivated after the original infection (such as the chickenpox virus, also responsible for shingles) or those which, initially perceived as fairly harmless, actually appear to be linked to serious illnesses. The most recent example is the Epstein-Barr virus, a herpes present in 90% of the population, which is clearly associated with the development of multiple sclerosis22.

Once all these factors have been taken into account, it seems illusory to identify THE most dangerous virus. But having them in mind enables us to know which viruses to keep a close eye on, and to consider ways of making each of them as safe as possible, in particular by abolishing the inequalities in access to treatment and prevention tools that still divide the world. Obviously, this debate must be extended to non-viral infectious agents : bacteria, fungi, and other parasites, such as the Plasmodium responsible for malaria. The One Health approach is also a reminder that humans are part of ecosystems and that health issues must be considered on an environmental scale23.