PrEP: preventing HIV infection without a vaccine

- PrEP is an HIV prevention method that has been available in France since 2016.

- It is a preventive treatment which, when taken before potential exposure to HIV, can prevent infection by up to 90%.

- PrEP works, with no significant side effects, provided that the treatment is adhered to.

- This treatment exists in different forms and with different compositions or methods of administration.

- The major challenge is to identify appropriate distribution methods (teleconsultations, dispensing in community centres, pharmacies, etc.) to increase accessibility worldwide.

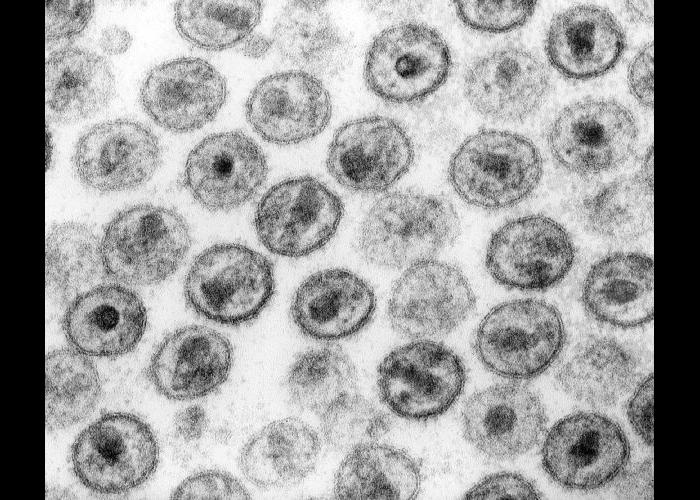

Forty years after the identification of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), responsible for Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS), the HIV pandemic has still not been stopped. More than a million people are infected each year worldwide1 and, in France, around 5,000 people a year are diagnosed as HIV-positive2. We still don’t have an effective vaccine against HIV. But did you know that, in addition to condoms, there is a prevention method that is over 90% effective? It has been available free of charge in France since 2016?

The early days of PrEP

Known as pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, the principle is simple: take antiviral treatment before potential exposure to HIV, to prevent infection by the virus. The first data confirming the effectiveness of this approach date back to 2010, via two studies. In the CAPRISA 004 trial, conducted in South Africa, a vaginal gel containing tenofovir (a compound that inhibits the HIV reverse transcriptase enzyme, essential to the virus functions) was tested in 889 young women3. In the iPrEx trial, conducted in six countries, tablets containing a combination of tenofovir and another reverse transcriptase inhibitor, emtricitabine, were used by almost 2,500 trans women or men who have sex with men4.

The idea is simple: take antiviral treatment before potential exposure to HIV, to prevent infection by the virus.

These studies produced similar results and, from the outset, highlighted three important points. Firstly, PrEP works. Preventive antiviral treatment reduced the risk of HIV infection by 39% in the CAPRISA 004 trial and by 44% in the iPrEx trial. Secondly, and this explains the relatively low efficacy rates, compliance is highly variable. Whether it was a vaginal gel used occasionally or a daily tablet, the protocol was far from being followed to the letter by all participants. Among the most assiduous participants, the protection afforded by the gel was 54% and that afforded by the tablets 92%. Finally, neither of the two trials showed any significant side-effects from PrEP.

Numerous clinical trials and real-life studies have since been carried out in various parts of the world, not just in developed countries. These trials involved different populations: men who have sex with other men, injecting drug users, serodiscordant couples, trans and cisgender women, heterosexual men, etc. The results obtained led the World Health Organisation (WHO) to recommend the use of oral tenofovir-based PrEP for all people at substantial risk of exposure to HIV in 20155. Substantial risk is defined as an incidence rate of more than 3 new cases of HIV per 100 people per year in the population concerned, in the absence of PrEP.

PrEP in France today

The profiles and situations of people likely to benefit from PrEP are extremely varied, particularly in terms of access to medical facilities, even in developed countries. However, the effectiveness of PrEP depends mainly on how regularly it is taken. A real-life study in France involving men at high risk of HIV infection showed, for example, that continuous oral PrEP protects against HIV infection to an average of 60%, and 93% when taken regularly6. To maximise the effectiveness of PrEP, it is therefore necessary to develop a range of products and methods of administration that meet the real needs and constraints of the people likely to use them.

In France, PrEP has been accessible and fully reimbursed since 2016, with the possibility of dispensing it without advance payment in CeGIDDs (free information, screening and diagnosis centres). It takes the form of oral tablets combining tenofovir and emtricitabine (Truvada, or its generics). They can be taken continuously, at the rate of one tablet a day at a fixed time, or occasionally. In the latter case, two tablets should be taken simultaneously 2 to 24 hours before the risk situation, then one tablet a day for the following two days. More than 80,000 people have used this prevention method since it was first made available, and the number continues to rise. Of these, 97% are men, with an average age of 36, living mainly in urban areas. However, the proportions of women, people living in rural areas and people benefiting from solidarity-based health cover are gradually increasing7.

Different forms of PrEP

PrEP does not necessarily mean oral tablets. In recent years, two other approaches have been added to the WHO recommendations. The first involves silicone vaginal rings, which must be worn for 28 days and gradually release dapivirine, another HIV reverse transcriptase inhibitor. Recommended by the WHO since 20218, this form of PrEP is used in several countries in sub-Saharan Africa, where women are the population most at risk from HIV. These vaginal rings are more discreet than daily tablets and offer greater autonomy, making them more accessible to some users. Based on the same principle, other delivery methods are being studied, such as vaginal films or soluble inserts under the MATRIX programme9.

Reducing the frequency with which drugs are taken not only makes them more discreet, but also facilitates patient compliance, which is a major factor in the effectiveness of PrEP. In this area, the WHO has been recommending since 2022 that cabotegravir be added to the arsenal of drugs available for PrEP10. Cabotegravir is an inhibitor of the HIV integrase enzyme, delivered in the form of injections every two months. Tested in men and women in different parts of the world, this form of PrEP is proving to be even more effective than standard oral PrEP. Figures vary from trial to trial, but on average, it appears to reduce the risk of infection by around 80% compared with oral PrEP, mainly because compliance is better with injections.

In September 2023, Apretude, an injectable form of cabotegravir, was validated by the European Medicines Agency11. The CABOPrEP clinical trial, designed to assess the efficacy of injectable PrEP in France, is due to start in early 2024. This approach, which requires only one injection every two months, is a welcome addition to the range of PrEP treatments available to people living with HIV, but it has its own drawbacks. The injections cannot be self-administered and are therefore aimed more at populations in contact with medical facilities. And, unlike other forms of PrEP, the use of cabotegravir seems to be associated with the appearance of some resistant strains of HIV, which calls for a higher degree of vigilance.

The future of PrEP

The remarkable effectiveness of pre-exposure prophylaxis is a revolution in the fight against HIV. To maximise its benefits, it is recommended that it be used in conjunction with other risk-reduction measures, rather than replacing them. But since PrEP is a recent development, and can take several forms and be based on different antivirals, it continues to evolve in line with research findings. Several compounds are currently being studied to assess their potential for use in PrEP, such as the reverse transcriptase inhibitor MK-852712 or lenacapavir, the first HIV capsid inhibitor, which has long-term efficacy and could allow injections every six months13.

The accumulation of studies has also highlighted a number of points to watch out for. In addition to viral resistance linked to cabotegravir, side effects associated with the tenofovir/emtricitabine combination used in Truvada and its equivalents have been identified. This affects fewer than one in ten people, but nausea, diarrhoea and abdominal pain may appear when this form of PrEP is started, and subsequently go away15. Very rare sub-clinical effects on the kidneys1617 and bone density18 have also been observed. A return to normal was observed after PrEP was stopped, but the recommendations have been adapted and this form of prevention is now not recommended by the WHO in cases of renal insufficiency (creatinine clearance of less than 60 mL/min).

Another form of oral PrEP, combining emtricitabine with a different form of tenofovir and causing fewer side effects, was then put forward: Descovy. However, Descovy is not available in Europe, due to a failure to reach agreement on its price and a lack of certainty about the benefits compared with Truvada19. The price of drugs remains a key issue, particularly in countries with limited resources, where most people affected by HIV live. Generally speaking, making PrEP and antiviral treatments available to all populations affected by the virus, in all countries, remains a major challenge.

The findings of the implementation sciences thus play an important role in the WHO’s recommendations on HIV20. To ensure that everyone finds a solution tailored to their needs, it is necessary to offer different medical devices (tablets, injections, vaginal rings, etc.), to use different compounds, and also to develop different distribution methods. Mobile devices, teleconsultations, dispensing in community settings, direct access in pharmacies: research is also needed to identify the solutions best suited to each context. Developing the best therapeutic approaches is pointless if they are not accessible to the people who need them.