Insomnia: when our brain refuses to let us rest

- According to studies, chronic insomnia affects between 15% and 20% of the French population.

- The factors that explain chronic insomnia are predisposing, precipitating and perpetuating.

- Precipitating factors can, for example, cause hypervigilance of the brain, preventing it from activating the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus, which is supposed to inhibit our state of wakefulness.

- According to the DSM-5, any patient experiencing these difficulties at least three nights a week for at least three months is considered to have insomnia.

- To break out of this vicious circle, treatments exist, and cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBT) is favoured.

An important early morning appointment can be enough to make it difficult to fall asleep. Is it out of fear of not waking up in time? It leads to worrying, brain activity and hypervigilance that are often incompatible with falling asleep. This example, one that is surely familiar to a lot of people, neatly summarises some of the things that can cause insomnia, and why our brains sometimes refuse to let us rest. If this situation sounds familiar to you, it only reflects the more occasional side of the disorder. Chronic insomnia, on the other hand, is the result of deeper and more complex mechanisms, which can cause this disorder to become long-term. A disorder which, moreover, is much more about hyper-arousal than sleep.

According to studies, chronic insomnia affects between 15 and 20%1 of the French population. This condition, which affects women (20%) more than men (10%), is still not well understood. Pierre-Alexis Geoffroy, professor at the University of Paris-Cité and head of the ChronoS Centre (Psychiatry, Chronobiology and Sleep) of the GHU Paris psychiatry & neurosciences, tries to explain it with the 3P factors model (predisposing, precipitating, perpetuating2): “We know that there is a genetic vulnerability. The heritability, and therefore the part of the disease linked to genes, is still decisive at 40%, which is equivalent to type 2 diabetes. In this risk area [Editor’s note: corresponding to the predisposing factor], precipitation can occur, linked to trauma, infection, depression or other forms of stress, both physical and psychological. The condition then has a chance to take hold, with perpetuating factors such as anxiety, and dysfunctional emotions and behaviours related to sleep.”

We are therefore dealing with an atypical disorder. First, it is not just a symptom of other conditions, but a disorder in its own right, often with comorbidities. Secondly, it is fuelled by several factors, both biological and psychological, which feed into each other. It is a kind of vicious circle which, once we are caught up in it, can only get worse.

When circuits jam

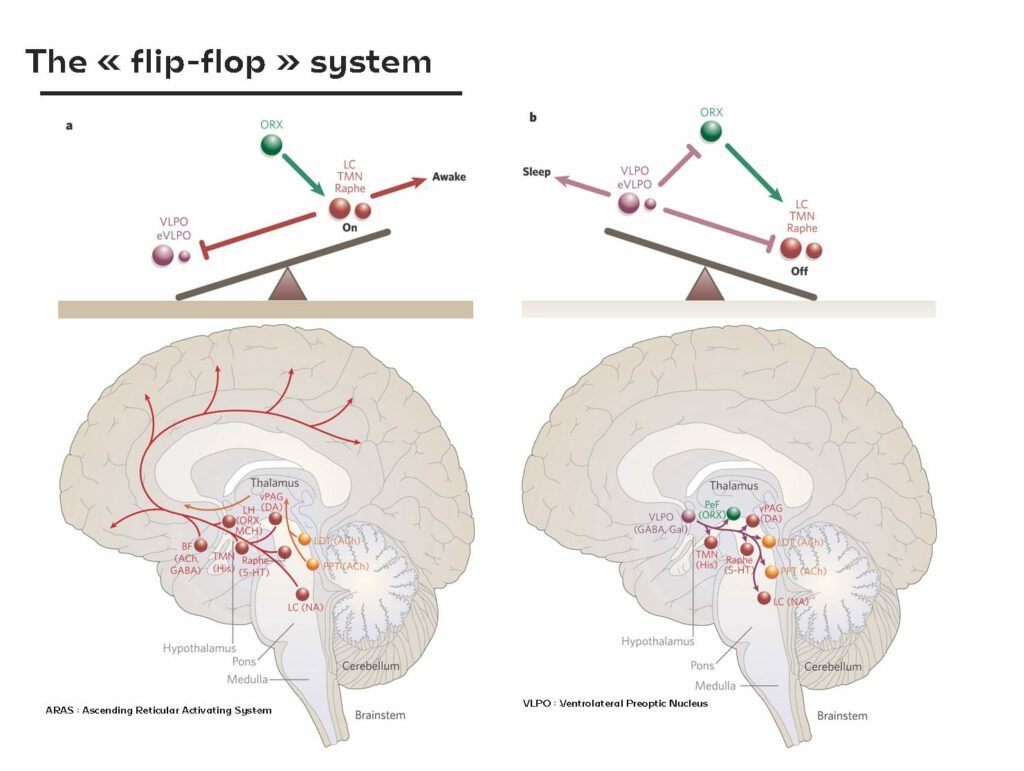

To understand how we become insomniacs, it is interesting to delve into the cerebral mechanisms at the root of this hyperarousal disorder. When it comes down to it, for our brain, sleeping almost means flicking the switch. This mechanism is also represented by means of a system known as the “flip-flop3”, like a seesaw, groups of neurons interact with each other to either activate or inhibit each other. On one side of the seesaw, we can say that we are in wakefulness mode, on the other in sleep mode.

“Our brain has a wakefulness system, called the ascending reticular activating system (ARAS),” explains Professor Geoffroy “This includes all monoaminergic structures, i.e. neurotransmitters such as histamine, serotonin, dopamine, noradrenaline, etc. Then comes the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus (VLPO), which is present to inhibit these arousal structures; these are GABAergic activities [Editor’s note : the neurons release gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), the brain’s main inhibitor].” In short: when awake, the ARAS is active and when asleep, the VLPO inhibits this activity. The switchover is gradual and, synchronised with our circadian rhythms, it is the orexin that stabilises the whole process. “A deficiency of this molecule (orexin) induces a disease called narcolepsy, causing central hypersomnia with unwanted excess sleep,” he adds. One of the new treatments for insomnia aims to target orexin to reduce this state of alertness.”

But how does this system fail when it comes to insomnia? This follows the logic of the 3Ps mentioned above: “Vulnerability, also known as predisposition, is certainly genetic, but it is also in constant interaction with the environment,” explains Pierre-Alexis Geoffroy. “The bed, the room, the noise, all factors that can complicate or simply impair the quality of sleep. Then there are precipitating factors that push the brain into hypervigilance, preventing it from triggering the VLPO, which is supposed to inhibit our state of wakefulness.” Stress, for example, through cortisol, its main hormone, delays falling asleep. At the same time, certain emotional circuits, such as those of the amygdala or the prefrontal cortex, will maintain a state of increased alertness. “Dysfunctional behaviour, due to the discomfort of insomnia, then appears,” he observes. “The patient starts counting how many hours of sleep they get, or their inability to fall asleep causes even more stress. From there, the illness becomes permanent, it settles in and becomes chronic.”

Breaking the vicious circle

Of course, chronic insomnia is still strictly diagnosed. According to the DSM‑5, an insomniac is any patient experiencing these difficulties at least 3 nights a week, for at least 3 months. It must also have a debilitating impact on the patient’s daily activities. This explains why, even though 50% of French people complain of insomnia, only 15% meet the criteria for a disorder or illness. According to Pierre-Alexis Geoffroy, this difference in prevalence may also be due to underdiagnosis: “We have published an interesting article5 that puts into perspective the cultural differences in the way sleep is perceived. In Germany, for example, patients tend to see a specialist very quickly – 20% will see a sleep specialist and 17% a psychiatrist. In France, it’s the other way around and the figures are alarming, because almost all people who identify a potential sleep problem will not go and seek advice from specialists.”

However, there are treatments available to break this vicious circle, with cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBTI) being the preferred option. “Sleep is very much a behavioural thing. There are conditioning factors, in addition to circadian rhythms, that encourage sleep. The bed, for example, becomes a real battleground in insomnia,” Professor Geoffroy explains. “Furthermore, we need to understand the origin of the disorder. If it is caused by depression, the depression will need to be treated first. However, if it is not recognised as a disorder in its own right, rather than as a simple symptom, the disorder can persist even once the depression has been addressed.” A prime example is the impact of disrupted nights due to post-pregnancy situations. Despite never having experienced any difficulty in sleeping, many women testify that, after pregnancy, their sleep habits are turned upside down. In these situations, parents are always on the alert, which clearly implies a state of hypervigilance. A number of women still suffer from insomnia after this period.

There is still a lot of confusion in the treatment of insomnia, reducing CBTI to simple sleep hygiene. “CBTI is a multicomponent therapy,” he adds. “Sleep hygiene is fundamental, but there is also cognitive restructuring to work on dysfunctional thoughts. Work on behaviour is also necessary, such as restricting the time spent in bed or stimulus control. This treatment works very well and will inhibit the arousal structures involved in insomnia.”

It is therefore possible to overcome this disorder, which greatly handicaps the daily life of the patient affected. Pierre-Alexis Geoffroy emphasises: “It is a disorder in its own right, and not just a night-time disorder, but a 24-hour one! We tend to underestimate the importance of sleep when we sleep well.” A recent study6 also shows that sleep disorders are the main risk factor for psychiatric disorders.