Is our inner voice our conscience?

- Self-awareness exists in two forms. It can be ‘minimal’, which we share with some non-human animals, or ‘elaborate’, maintained throughout time, and unique to humans with the notion of time.

- Minimal self-awareness, consisting of pure perceptual experiences, without language, seems to exist in small infants. Elaborate self-awareness seems to be built upon it by bringing lexical and syntactic tools into play.

- Through the practice of language, human beings create a sense of self extended over time. By inhibiting the production of overt language aloud, by internally simulating it, human beings can secretly develop their self-awareness.

- Autobiographical memory can also be enhanced by endophasia, including the ability to evoke memories, recall a past event, by speaking internally.

- In the first two years of life, autobiographical memories are virtually absent. It has been suggested that language development would allow the structuring of self knowledge.

I say to myself…

Therefore I am ?

Language allows us to communicate our thoughts, emotions, and feelings to others – its communicative function is essential. We speak with others, but we also speak to ourselves, internally, to think. Hence, language also has a cognitive function, as Egyptian scholars, and Greek philosophers from Heraclitus to Aristotle, via Plato, already knew. Later, Descartes, in the Discourse on Method1 revealed a third essential function of language – metacognitive – whereby the thinking subject is aware of itself: “I think, therefore I am”, as he wrote.

Language has indeed a crucial role in self-awareness, which can be defined as the recognition of one’s own existence. But the Cartesian notion of the self as a stable and unified substance has been questioned, as the self is dependent on situations – it is in perpetual motion. Contemporary reflections in philosophy, linguistics and cognitive sciences have made it possible to put forward new elements of response to this question of self-awareness. We can consider that it is built up through language, starting from a so-called “minimal” or primitive self-consciousness, shared with certain non-human animals2. The elaborate self-consciousness, and the mental positioning in time, called autonoetic consciousness, is based on language and seems to be specific to human beings.

Language as an instrument of self-awareness

Minimal self-awareness, consisting of pure perceptual experiences, without language, seems to exist in infants. Visual perception and somatic proprioception makes it possible to associate the feeling of movement of one’s body with the observation of one’s body in motion. In infants, it contributes to the experience of a differentiated self, situated in space, with a bounded body.

Elaborate self-awareness is scaffolded on minimal self- awareness and brings lexical and syntactic tools into play. The acquisition of pronouns by children, around the age of two, enables them to differentiate between “I” and “you” or “mine” and “yours”. It indicates the conscious emergence of the contrast between the self and the other. Then, with the increase in vocabulary, demonstratives, adverbs, and the use of verb tense, which all organise spatial and temporal relations, with the self as the origin (“this, here, now, yesterday, tomorrow”), children can better represent themselves and others. In this way, they can construct narratives about past memories and future intentions.

Throughout life, thanks to language, human beings create an identity, or rather an ipseity, a sense of “self” expanded over time. Thus, while language obviously enables inter-human communication, its major role in thought and in autonoetic consciousness has favoured its internalisation. By inhibiting the production of overt language, by internally simulating language, human beings can secretly develop their self-awareness.

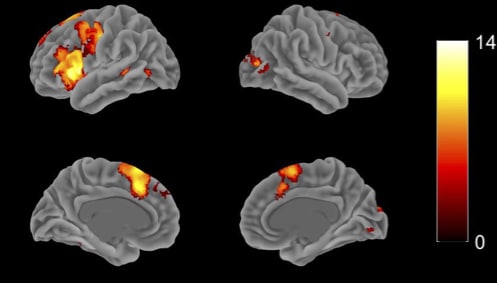

As we have shown at the Laboratoire de Psychologie et NeuroCognition in Grenoble, in an fMRI neuroimaging study, during the production of inner speech, the brain regions of overt speech are activated, as well as regions of the prefrontal cortex, involved in inhibition4. The possibility of inhibiting and speaking internally to oneself, what Georges Saint-Paul called in 1892 “endophasia”5, thus seems fundamental. By talking to ourselves to recall memories, plan things, imagine others, or even to engage in self-critique, we can create an extended sense of self-awareness over time.

Endophasia: our inner language

The links between endophasia, or inner language, and memory have been extensively studied by psycholinguists. In particular, inner language interacts with working memory, the short-term memory that allows us to store and manipulate information temporarily to accomplish a task. To remember a telephone number or a code to dial, to remember a shopping list, we can say them internally, in a loop. The internal repetition of the words to be remembered allows the information to be temporarily held in memory. This type of working memory is based on the sound of words. This can be verified with an experiment that has been replicated many times, in which participants are asked to remember a list of words6.

For example:

camp, foot, nail, floor, wall

Or :

bat, mat, hat, pat, cat

Words that are pronounced the same are likely to be confused, resulting in poorer recall of the second list than the first. This is known as the phonological similarity effect, an effect that reveals that participants use inner repetition of words to retain them.

Autobiographical memory can also be enhanced by endophasia. One can evoke memories, recall a past event, by talking to oneself internally. Autobiographical memory is based on narrative constructions that allow events to be organised coherently in time, and to be inscribed in a personal history. Research on the development of memory in children indicates that in the first two years of life, autobiographical memories are virtually absent. It has been suggested that language development that would later allow the structuring of self knowledge and the creation of autobiographical memories organised in time.

Internal and external language: the chicken and the egg

When do children start talking in their head? For the psychologist Vygotski7, inner speech is inherited from overt speech, via a gradual process of internalisation that takes place during childhood. Like Piaget before him, Vygotski observed that children begin by speaking aloud to themselves. In this phase, which Vygotski called ‘private speech’, the child plays alone and reproduces dialogue situations. Then, little by little, the child learns to inhibit this behaviour and internalises it. Their private speech becomes their internal language between the ages of five and seven.

Recent experimental psychology studies confirm the hypothesis that the child can speak internally from this age. A classic experiment uses the Tower of Hanoi game. If, while performing the task, children are prevented from talking to themselves in their head, by having them repeat aloud “ba ba ba”, it is observed that their performance decreases. This suggests that the child uses inner speech for action planning, as early as about five years8. It is more difficult to know whether inner speech is used by children in such tasks at earlier ages, as their reduced performance may simply be related to difficulties in concentration or reasoning.

However, some recent research, notably that led by Sharon Peperkamp in Paris9suggests that infants may be able to internally evoke the sound of certain words as early as 20 months, before they are able to articulate them aloud. The researchers from the Paris team presented 20-month-old infants with images of objects or animals, followed by a voice naming the image. They used both short (such as “cat”) and long (such as “banana”) words. After the picture and sound were presented, the child saw two empty boxes on the screen. Then the picture filled in one of the boxes: the left box for short words and the right box for long words. This step was repeated several times until the infant understood the implicit rule: short words on the left, long words on the right. After this familiarisation stage, the researchers presented a picture without the sound, for example a telephone. They observed that the infants anticipated and looked to the right side even before the telephone filled the right-hand box. This experiment suggests that twenty-month-old infants can internally evoke the sound of words and thus categorise words as mono- or tri-syllabic, while they are still unable to articulate them aloud.

The development of certain forms of inner language could thus precede, or even be a determining factor in, the development of oral language. The question remains open. Do such experiments reveal automatic associations between an image and a mnemonic sound trace, or are they evidence for actual inner speech production?

Interview by Pablo Andres

For more on the topic of inner language (or endophasia):

- « Who says ‘I’ in me? », her book to be published by Denoël in May 2022: The mystery of inner voices

- A scientifique impromptu, a show created with the actor Mickaël Chouquet of the group n+1, Les ateliers du spectacle : Des voix dans la tête (voices in the head)

- An ongoing online survey on mental imagery and inner language