Immortality, an ancient fantasy revived by transhumanism

- Transhumanism is a school of thought that promotes the idea of surpassing the human condition.

- With life expectancy rising steadily over the last few decades, advances in neuroscience are bringing the ideological aspects of this school of thought to light.

- Over the centuries, the definition of death has evolved considerably, but today it is considered to be the absence of brain activity.

- Researchers have identified distinctive signals associated with death and resuscitation, making the definition of death more complex from a neurophysiological point of view.

- Now, some transhumanist movements are no longer aiming for immortality, but amortality, i.e. a considerably prolonged life in good health.

- Immortality is a long-standing human goal, but what is new is the techno-scientific justification for this ambition.

From being “brain dead” to the “mind download” envisaged by transhumanists, the boundary between life and death continues to be shrouded in mystery. But in the face of the hopes of immortality that they raise, the limits of scientific reality and the human condition must be faced. Recent advances in neuroscience have led to a rejection of this desire to “kill death”, which has more to do with ideology than with a serious techno-scientific project.

Thanks to advances in science and medicine, humanity has never ceased to delay its own demise. While a contemporary of Charlemagne was born with a life expectancy of barely 30 years, INED predicts that a citizen of the European Union born in 2022 will live an average of just over eight decades. But some people imagine going even further. Recent scientific revolutions in artificial intelligence, genetics, biology and neuroscience, combined with the emergence of transhumanism (a movement that promotes the idea of transcending the human condition), have brought the quest for immortality back to centre stage, or at least for a significant extension of life.

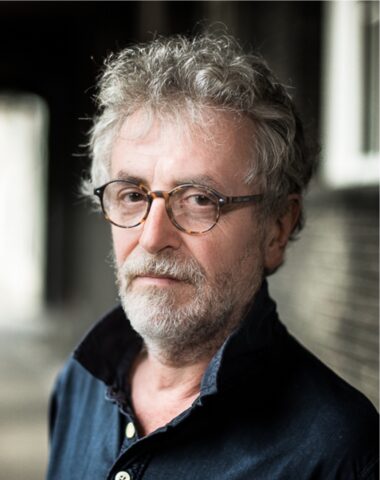

But before we can understand how and why we delay death, we need to be able to define it. And the question is not so simple: “As a scientist, I don’t know what death is”, admits Stéphane Charpier, professor of neuroscience at Sorbonne University and director of the Brain Neuroscience team at Inserm. For him, it is a “primary concept” that only takes on meaning in opposition (“in the negative”) to life. This is why his work involves “studying death by trying to understand what is happenng in a brain that is still alive”.

The corpse with the beating heart

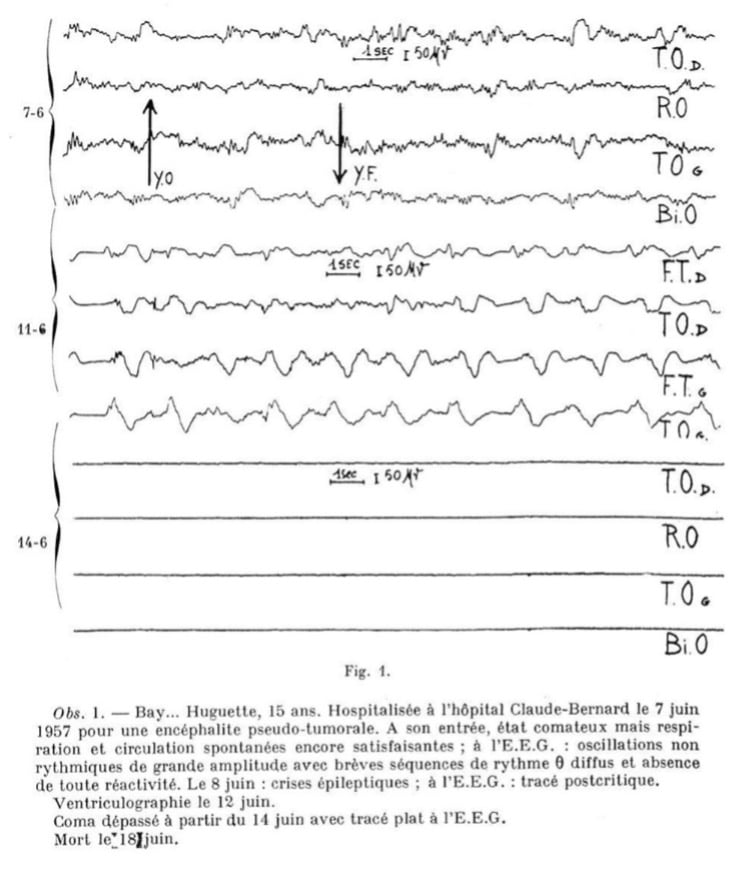

The idea that a human being with a beating heart is necessarily alive is still widely held. However, when Pierre Mollaret and Maurice Goulon discovered brain death1 in the middle of the 20th century, they disproved this principle and “engendered,” according to Stéphane Charpier, “a new status of human existence”, by describing the possibility of having a corpse with a beating heart, but whose brain has been destroyed. The two resuscitators were in fact the first to conceptualise the principle of brain death. They defined this status as a “coma in which, in addition to the total abolition of the functions of relational life (editor’s note: absence of muscular and nervous reactivity), there is not only disturbance, but also total abolition of vegetative life (editor’s note: absence of spontaneous respiration)”.

In this way, the cardiocentric vision of existence is no longer relevant and, from a medical point of view, what makes a human being not dead is no longer his beating heart, but his living brain.

Since 2012, the WHO has also adopted this brain-centric viewpoint in its definition of death: “the permanent and irreversible disappearance of the capacity for consciousness and of all functions of the brain stem”. A human being is therefore considered to be alive as soon as his or her brain is capable of generating “electrical background noise”, as Stéphane Charpier points out. This phenomenon, which results from the brain’s spontaneous, endogenous activity, can be measured using an electroencephalogram or microelectrodes that scientists insert inside neurons.

Immortality, the permanent horizon of transhumanism

Electro-neuronal studies enable researchers to “differentiate three physiological dimensions of existence: living, awake and conscious”, to which particular electrical signatures correspond. As Stéphane Charpier, author of La science de la résurrection2, explains, this triptych makes it possible to understand that “what makes a human being not dead is no longer just his beating heart, or his ability to breathe spontaneously, but his capacity to produce a conscious subjective experience.”

So, if death coincides with the inability to be conscious, does the quest for immortality cherished by transhumanists amount to keeping our brains alive after our bodies have failed us? “Not exclusively,” replies Cecilia Calheiros, a sociologist specialising in health and religion who devoted her doctoral thesis to the subject. “Transhumanism aims for the end of the human as it exists and the advent of a new one,” she sums up, “which will be either immortal or amortal, depending on whether you’re a North American or French transhumanist.” By amortal, we mean a human being whose lifespan in good health is considerably extended, without being eternal. In short, the transhumanist project amounts to proposing a society where “the human condition frees itself from its biological limits”.

The wave of death is not fatal

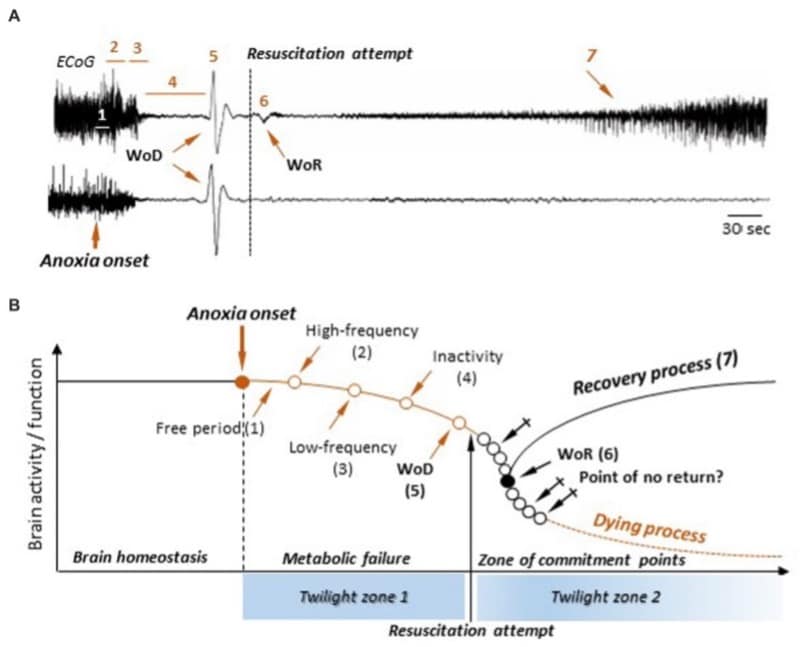

In 2011, bored by a scientific presentation at a conference, Stéphane Charpier chose to read an article published in the journal Plos One3, the title of which mentions a mysterious “Wave of Death”. In it, the authors assess the brain activity that occurs at the moment of death, “by studying what happens in the brain of a rat before, during and after decapitation”, he explains. And, as expected, “they found that this activity died out very quickly, but that after a while a gigantic wave appeared on the electroencephalogram, which had flattened out!” This is what the Dutch researchers call the “wave of death”, suggesting that it is the last signal a brain produces before it finally shuts down.

Nothing less was needed to arouse the neuroscientist’s curiosity, and to get his Inserm team at the Institut du Cerveau (Pitié Salpetrière Hospital in Paris) involved in a project to study this phenomenon in greater detail. “We abandoned the principle of decapitation and set up a protocol enabling us to switch off the brain, then reanimate it afterwards, while studying brain activity using microelectrodes inserted into the neurons of our test subject,” sums up the researcher.

After confirming the neuronal phenomenon of the wave of death, when the test subjects were reanimated, the researchers witnessed the appearance of “a second wave! […] An electrical sign of the brain’s return to life”, which they named the “reanimation wave”. The scientists have thus characterised two neuronal markers that help decipher the boundary between life and death. Parameters are still lacking to define death precisely from a neurophysiological point of view, but their work makes it possible to attribute a signature to two distinct states: “I may be dying” and “I may be coming back”.

A flat electroencephalogram doesn’t necessarily mean that everything is over, which is why Stéphane Charpier says that “death is an asymptote”. A curve whose point of convergence with the end line is a more than indecisive horizon.

An illusion of eternity

According to those who claim to be part of this movement, immortality is only a “speck on the horizon” for the time being. To achieve it, some transhumanists advocate a biological approach to counter-aging (or “‘longevity”), with the aim of halting or even reversing the aging process. Others believe that “true freedom consists in detaching oneself from one’s physical body”, says the researcher. In this case, the essence of existence lies in the brain, whose memories and functioning should be preserved “to make it imperishable” by cryogenics, as proposed by the Alcor Life Extension Foundation in the USA, or by mind uploading processes. While these methods fail to approach the realm of the possible, they do have the advantage of fueling the imaginations of many artists and science-fiction writers.

Illusory, then? “Without a doubt,” says Stéphane Charpier. In his view, “the transhumanist project is a metaphysical fable. We can increase our life expectancy, correct defects and compensate for certain weaknesses, but increasing the human being as an entity, or cryogenically storing their brain, is quite simply a pipe dream.” The neuroscientist acknowledges that humans are capable of producing artificial neural networks, of “tinkering with brains”, but considers it unimaginable that a machine could produce, or even replicate, the neural processes underlying subjectivity.

The means justify the end

Ultimately, the innovative character of transhumanism does not lie in the quest for eternal life. “What is new is the assertion that immortality is plausible, thanks to a discourse based on techno-scientific advances. Transhumanist objectives are thus convincing players in key spheres of our societies: industry, research, health, etc.”, points out Cecilia Calheiros. As a result, transhumanism is, in her view, “the most exacerbated expression of neoliberal society, which urges everyone to be the best version of themselves and to constantly improve their skills.” The sociologist sees this movement “above all as an ideology, which reinforces a power that is already present.”

In the transhumanist context, the maxim that the end justifies the means no longer holds true, since this end (death) is destined to disappear. The transhumanist myth is based on a reverse movement in which the means (technosciences) justify a new end (immortality/amortality). The ambition is “infinite mastery of the world” and of the biological conditions of existence, which brings transhumanists back to the myth of Frankenstein, according to Stéphane Charpier. In his view, “with this novel, Mary Shelley wrote the first transhumanist text. She imagines a body made of fragments of corpses that lives and fulfills the dream of transhumanists: to deprive human beings of death.”

The quest for immortality and longevity has punctuated the history of mankind since its earliest beginnings. It is embodied in countless myths about mortals who dared to aspire to the immortality of the gods and were condemned to torment in return (Prometheus, Icarus, etc.). The rise of transhumanism is a modern update of this ambition. Unfinished, this movement comes up against the wall of objectivity and the scientific approach. “Can we be conscious without a body? Can a machine really produce subjectivity?” asks Stéphane Charpier rhetorically, by way of conclusion.

As long as transhumanists can’t provide an objective demonstration or proof that it’s possible, death will remain the shared horizon for each and every one of us.