The BRICS+: economic alliance or future private club of raw materials?

- The BRICS+ are a group of countries that are economically heterogeneous, but which are demonstrating their desire to become global powers.

- The group has expanded with the entry of Saudi Arabia, Iran, the United Arab Emirates, Egypt and Ethiopia.

- They have become major players in the oil and metals markets, challenging the dominance of the US dollar in world trade.

- The group has become one of the pillars of global food security, producing 42% of the world’s wheat, 52% of its rice and 46% of its soya.

- Despite their cross-investment and partnerships, the political and economic differences between the BRICS+ limit their unity as an ideological bloc.

- Europe should be concerned about the risks of cartelisation of metals by the BRICS+, which underlines the need to develop its own extractive industries and strengthen its security of supply.

From the acronym BRIC, coined in 2001 by economist Jim O’Neill to describe the economic potential of Brazil, Russia, India and China, to its evolution into BRICS with the addition of South Africa in 2011, and then to its recent transformation into BRICS+ in August 2023, the group has come a long way! This group, which is highly heterogeneous in economic terms (growth dynamics, demographics, level of industrialisation, sectoral specialisation, etc.), has above all demonstrated its ability to forge closer political ties and this shared (but also competing) desire to become global powers.

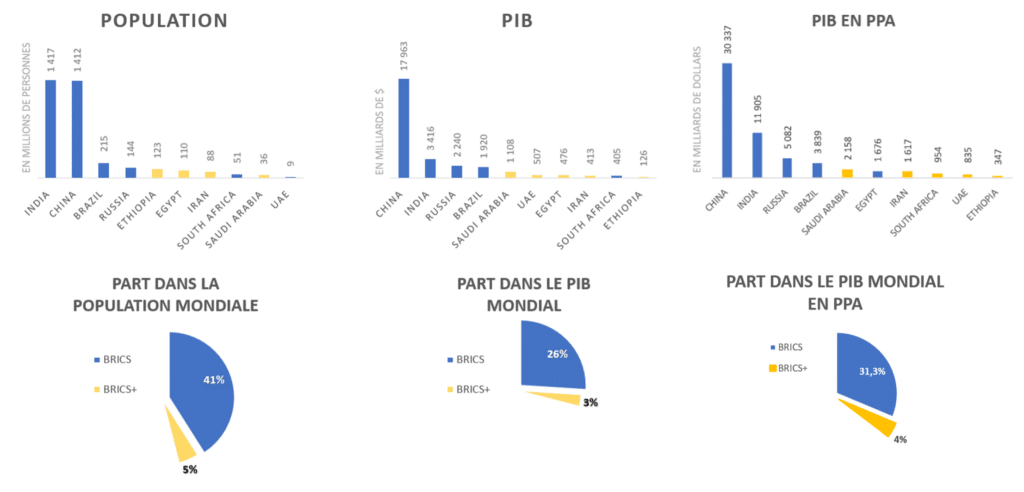

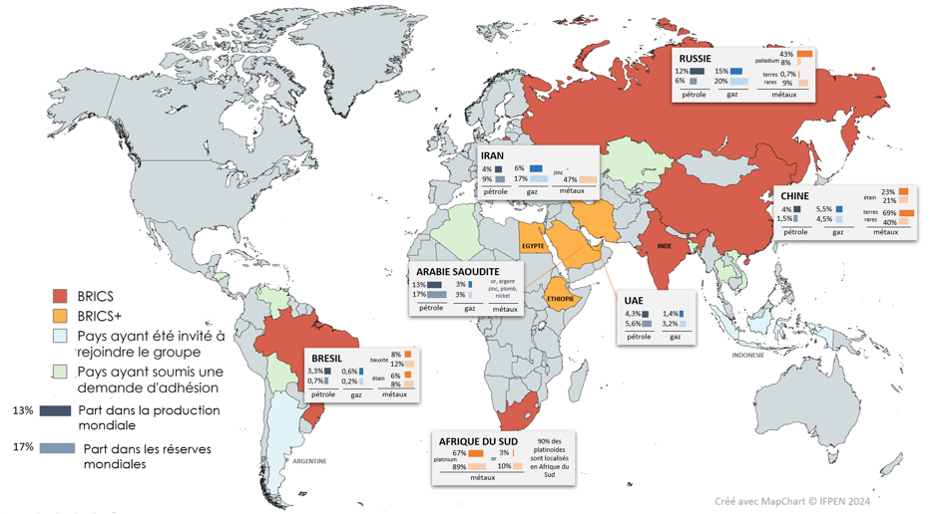

The evolution of the BRICS into BRICS+, with the addition of Saudi Arabia, Iran, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Egypt and Ethiopia in 20241, is reflected in their larger share of the world’s population (46%) and international GDP in dollars (29%). The main changes are likely to be seen in energy and metal commodities. Indeed, by including some of the biggest exporters or holders of reserves on the hydrocarbon markets (oil and gas) and members of the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), the BRICS+ are positioning themselves as genuine potential competitors to the dollar on the oil markets, and therefore to the United States. In the metals sector, the sheer weight of Brazil, China, Russia and South Africa makes the BRICS major players on the markets. And that’s not counting Saudi Arabia, a future mining power and the possible future integration of Indonesia, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Chile.

Controlling the key raw materials sectors is now fundamental in the context of global decarbonisation. Metals have become increasingly important due to their growing use in many low-carbon technologies such as photovoltaic panels (aluminium, silver, copper, silicon), wind turbines (aluminium, copper, nickel) and electric vehicles (cobalt, copper, lithium, manganese, etc.). Are we therefore in danger of seeing the birth of a new alliance based on raw materials, which would use them as diplomatic leverage in a world of climatic, economic, and geopolitical insecurity?

An increasingly important group in the global economy

What the BRICS+ have in common is that their development has been underpinned by state-building and a prominent public sector. Many of them are members of the WTO2 and have taken advantage of the momentum of globalisation and trade to become involved in international trade through the supply of raw or processed natural resources. While the BRICS+ account for around 25% of global exports, intra-BRICS+ exports represent only 15% of the group’s exports: the G7 countries remain the main partners of these dynamic economies3. Their economic models are partly based on the exploitation of raw materials. In 2023, the BRICS group will account for around 30% of the world’s GDP and 46% of its population, while the G74 will account for 10% of the world’s population and 45% of its GDP. However, if we look at world GDP in purchasing power parity (PPP)5, the BRICS account for 31% compared with 29% for the G7: a historic overtake that underlines the group’s dynamism. And the recent enlargement of the BRICS confirms the group’s economic and demographic weight on the international stage, with 34.5% of world GDP in PPP6.

Since 2011, the members of the BRICS (and now the BRICS+) have met annually to discuss cooperation between their members, with the stated aim of increasing their influence in international negotiations. In 2014, the group created the New Development Bank, known as the BRICS Bank, with an initial capital of 100 billion dollars to encourage investment in infrastructure in developing countries7. The countries have also signed a framework agreement designed to support members’ liquidity in the event of difficulties with their balance of payments. Economic and financial agreements, partnerships, joint investments… The BRICS offer an alternative form of governance on the world economic stage. They also form a group that is currently attractive to other countries, but whose membership criteria remain unclear, with enlargement requiring unanimity.

The entry of Saudi Arabia and the UAE has strengthened the group’s global influence in the energy sector. The BRICS+ now account for 43.1% of oil production and 44% of oil reserves8. As for gas, they account for 35.5% of global production and 53% of global reserves9. The Chinese President’s support for the entry of countries such as Nigeria and Kazakhstan also signals China’s desire to strengthen the BRICS+’s influence in energy10. In terms of food commodities, the enlarged group currently produces 42% of the world’s wheat, 52% of its rice and 46% of its soya11. Along with Brazil and Russia, its exports to world markets make it one of the pillars of global food security1213.

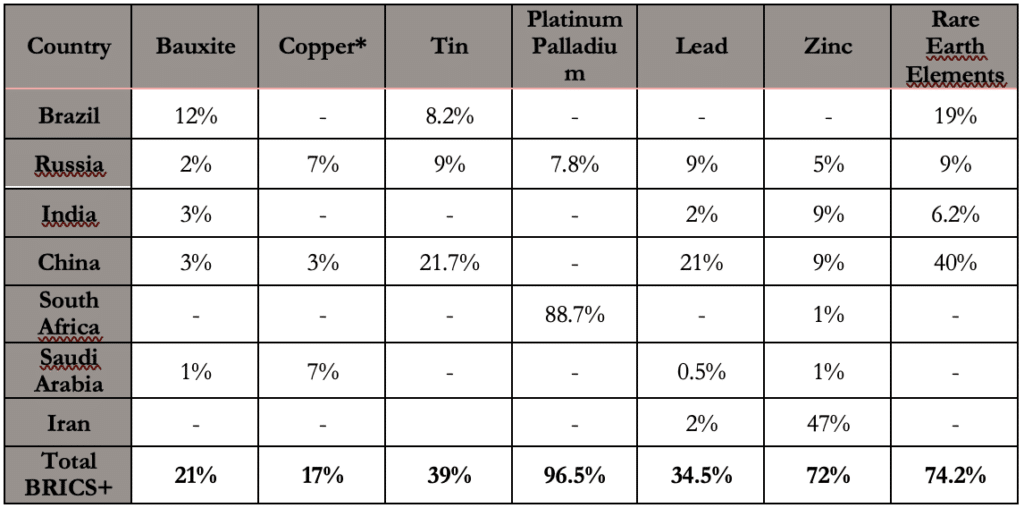

BRICS+, a leader in metals markets

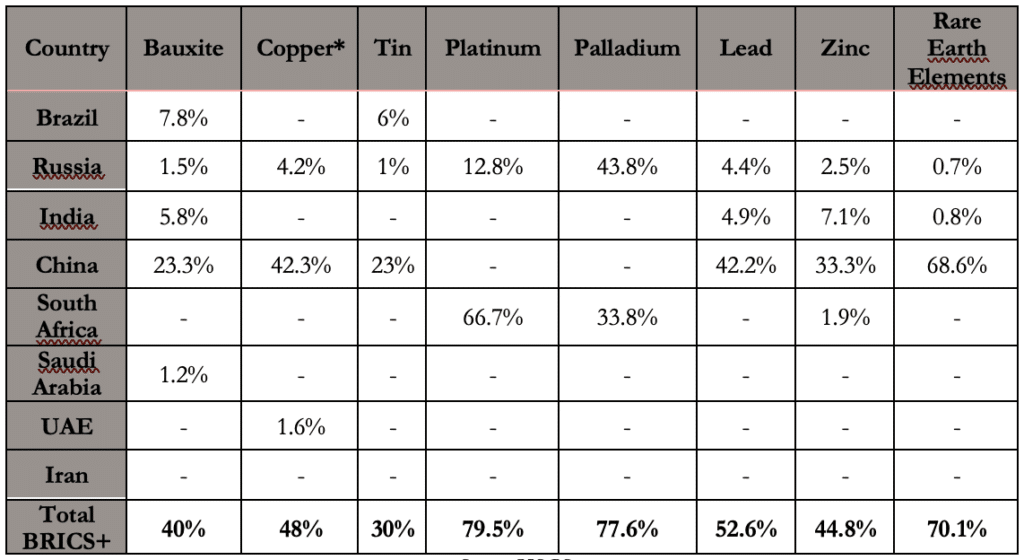

At a time when metals are becoming central to the low-carbon and digital transition, the BRICS+ now occupy a dominant position in both the production and global reserves of certain critical metals such as platinoids, rare earth elements and copper.

By boosting their production and developing the mineral potential of their subsoil, each BRICS+ country is seeking above all to secure its own metal supplies and strengthen its position as a producer of critical raw materials. For China, this strategy of securing supplies is aimed at ensuring the long-term viability of its production of low-carbon technologies such as electric vehicles and solar panels. Member countries are also diversifying their investments to strengthen their position in other strategic metals that they do not produce. Saudi Arabia illustrates this polymorphous strategy for preparing for the post-oil era: developing the domestic mining industry, stimulating foreign investment (FDI), launching partnerships and aiming to become a regional hub for energy and metal trade14. For instance, the Saudi monarchy has announced that it is taking a stake in the Brazilian group Vale through its mining company Manara in order to secure its lithium and nickel supplies15. At the end of 2010, it also launched production of titanium sponge, a key raw material for the arms and aerospace sectors, with a project bringing together the Japanese company Toho and the Saudi company AMIC16. By 2022, the Saudi economy will be the world’s 16th largest exporter, according to the Observatoire économique de la complexité17.

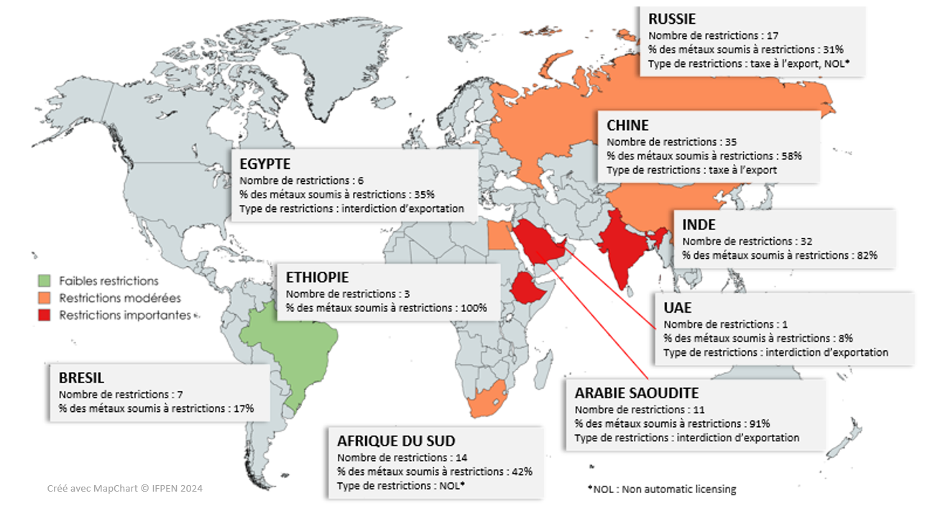

In addition to their abundant resources, the group’s dominant position is also reflected in their common policy of restricting exports of strategic metals18. All the BRICS+ countries have introduced different restrictions on the export of metals, ranging from export taxes to outright bans and the non-automatic allocation of licences to companies. For example, in December 2023, China banned the export of technologies needed to process and refine rare earths, in the name of national security19. While China currently extracts 60% of rare earth elements, it processes 90% of the world’s production. The aim of the ban is therefore to secure China’s technological lead20 in these essential metals, which are used in the manufacture of permanent magnets used in off-shore wind technology, electric vehicle engines and smartphones. In the future, a coordinated approach to restrictive policies could undermine the energy security of Europe and the United States, both in terms of supply and technology.

A solid metal bloc?

The BRICS+ are strengthening their ties through cross-investments and partnerships, which seems to be reinforcing a bloc logic, particularly in the metals and transition technologies sectors. The entry into the club of the UAE and Saudi Arabia, which have financial capacity, strengthens the group’s investment capabilities. Saudi Arabia has launched partnerships with Brazil (Vale), China (Human Horizons) and Egypt. Furthermore, although the United States and China are both investing in the BRICS+, the composition of their FDI is very different: Chinese FDI focuses on manufacturing, construction and electrification, while American FDI is concentrated in the services, R&D and ICT sectors21. China is therefore seeking to gain greater control over the technological value chains at the heart of the low-carbon transition. The BRICS+ group therefore seems to be partly structured around financial flows in strategic markets such as metals.

However, to really develop a metals bloc, the BRICS+ need to integrate a few more countries. The addition of key members such as Chile, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Indonesia would radically increase the group’s dominance of the metals market. The DRC accounts for 74% of the world’s cobalt production and 55% of its reserves, while Chile is a major producer of copper and lithium. While the DRC has expressed a desire to strengthen its ties with the BRICS+22, the other two countries do not currently appear to be interested in an alliance with the bloc. After hinting that it would join the BRICS+ following an invitation23, Indonesia finally refused to join, questioning the real economic gains behind this membership24. Southeast Asia’s rising economy, which produces 50% of the world’s nickel, therefore prefers to remain independent and non-aligned, as it has been in the past.

These discussions about whether or not to join the BRICS+, despite the convergence of their economic interests, raise questions about the unity of the bloc. The BRICS+ share a desire to compete with the major Western economies, to assert themselves on the international stage and to reform the international monetary system, but the members are divided on several issues. Heterogeneous political regimes, a lack of economic convergence, geopolitical disagreements, opposing alliances, notably with the United States, and regional competition between China and India or Indonesia – all these factors hamper the unity of the bloc. It would appear that joining the BRICS+ is part of a strategy to diversify partnerships, rather than the participation in a new ideological bloc. Today’s international relations are based on multi-alignment and transactional logic: each player will forge an ad hoc and sectoral alliance in line with its own interests. It is this logic that has enabled Saudi Arabia to renew its strategic and security partnership with the United States while strengthening its ties with China and joining the BRICS+. On the issue of metals, however, the interests of the members are fairly convergent – control over the production of strategic metals and therefore control over prices, a dominant position on transition issues, a monopoly on technologies – which makes the development of a mineral bloc, or at the very least the coordination of extractive and trade policies, credible.

What are the risks for Europe when faced with a metals bloc?

The risk of cartelisation is forcing other players, and Europe in particular, to consider the place of metals in future international relations and the risk this represents for their own supplies25. Europeans have had a rude awakening on the gas markets following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine26 and metals have become a central issue for Europe, as the costs of the ecological transition will depend heavily on the price of these raw materials. Aware of the stakes, in 2023 the European Commission published a regulation, the Critical Raw Material Act, to ‘support the development of domestic capacities and strengthen the sustainability and circularity of supply chains27’ for critical raw materials. However, this is a sign of the growing tension in these markets and a growing awareness of the return of conflict to their core. These tensions could ultimately provide an opportunity for Europe to develop its own extractive industries on its own soil, which would meet the sustainability standards that the Old Continent has set itself, while exporting its environmental standards to the rest of the world. Coupled with a policy of sobriety and a major recycling system, European mines would improve security of supply by reducing our dependence on a potential BRICS+ cartel.