Long dominated by the Americans, the rapidly expanding military drone market is seeing the arrival of new state players, including developing countries with a regional power base. As the range of products expands and the repertoire of uses continues to grow, the armed forces are increasingly drawing on the resources offered by civilian manufacturers.

A rapidly growing market

The global market for civil and military drones was worth $4bn in 2015 and it is now booming. A Senate report estimated in 2017 that it would reach $14bn by 20251, and a specialised institute has put forward the figure of $72bn by 2028, with an average annual growth rate of 14.4%2.

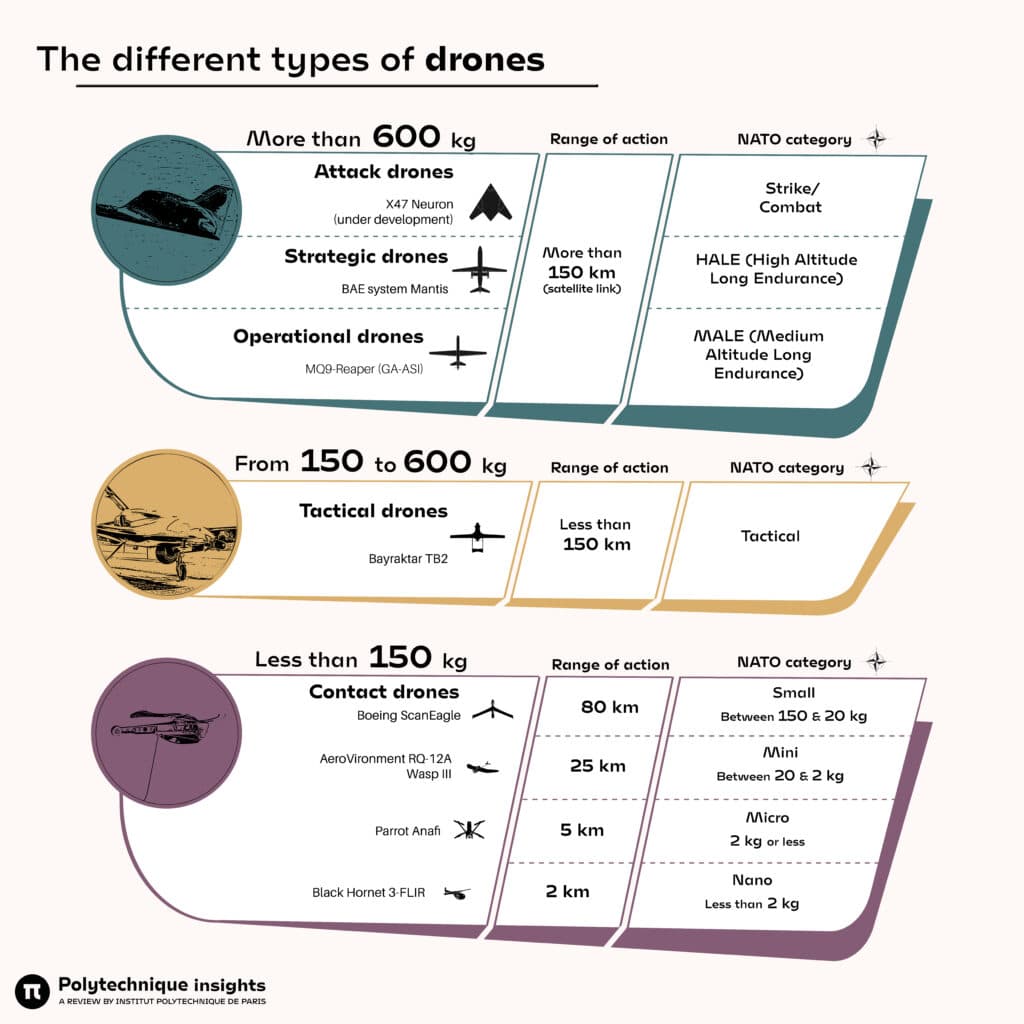

This growth is due to the sharp increase in demand for drones used by the military, for everything from surveillance to lethal intervention and transport. Hundreds of companies are currently working on drone technology on both a small and large scale, and state and non-state actors are looking to integrate drones into their military programmes. NATO distinguishes between several types of military drones.

The most significant sector, both tactically and in terms of the market, is that of MALE (Medium Altitude Long Endurance) drones. Initially dominated by the Americans, with the General Atomics Predator, the first examples were delivered in 1995 and were armed in the early 2000s. For a long time, they had a monopoly with 360 units delivered (mainly to the US armed forces), but were gradually replaced by the Reaper, of which more than 300 units were delivered to the US armed forces. Allies of the United States – mainly but not exclusively within NATO – have acquired several dozen models.

Alongside the United States, the other leading country in the field for a long time was Israel, with Israel Aerospace Industries, which first launched the Hunter in the 1990s and then the IAI Heron, presented at the Paris Air Show in 1999. The latter equipped the Tsahal since the mid-2000s and was sold for export, notably its French version – the Harfang from EADS. Europeans do not have much of a presence in the MALE UAV market, neither as customers nor as manufacturers. The Talarion project by EADS was abandoned in the early 2010s due to lack of funding, and a new MALE UAV project is struggling to get off the ground.

Depending on the tenets of various national armies, lethal use may be authorised but since the 2010s, combat drones have been used more and more frequently. Alongside the ultra-sophisticated aircraft developed by the Americans and Israelis, Turkey launched the famous Bayraktar TB2, developed by Baykar from its predecessor, a surveillance drone launched in 2007. The TB2 flew for the first time in 2014 and was armed in December 2015.

New manufacturers

Considered a ‘low-cost’ ‘drone due to its price ($5m) – four times less than the American Reaper (it is also smaller) – the Bayraktar borrows some of its technologies from partner countries, such as Canada for its L3Harris WESCAM MX-15D electro-optical system. But the involvement of these drones in the second war in Nagorno-Karabakh led Ottawa to ban the export of these systems. The idea of a drone industry as an assembly of applications provided by subcontractors must therefore be considered with caution as is often the case in the military field, these are sovereign technologies that the country building them must be able to use.

The Bayraktar can carry four intelligent laser-guided munitions capable of destroying armoured vehicles. It has been used in various theatres of operation, including Syria and Libya, but above all in Ukraine, where the 20 or so examples deployed enabled Kiev’s forces to reverse the tactical advantage given to Moscow by its superiority in the field of armour.

Some drones can carry four smart, laser-guided munitions capable of destroying armoured vehicles.

Next to Turkey, Iran is another reference country, with a MALE drone, the HESA Shahed-129, and the Shahed-191 stealthy flying wing, both equipped with lethal missiles. Russia reportedly placed an order for these UAVs in 2022, for use in Ukraine. The Russians also manufacture their own drones, as do the Indians, South Africans, Pakistanis and, of course, the Chinese, whose Wing Loong (1 and 2) and CaiHong (1 to 6) have been sold to other countries.

Europeans are not building MALE combat drones. When Germany decided in 2018 to acquire MALE drones, it chose Israeli Heron TPs, which it decided to arm in 2022. However, Europeans – mainly the French and the British, together with German and Italian suppliers – have developed different models of tactical drones used for surveillance and intelligence purposes. EADS’ Barracuda and BAe’s Taranis have remained in the planning stage, while Safran’s Patroller is used by the French army and the Egyptian armed forces. Thales’ Watchkeeper WK450 is in service with the British Army. Today, the Organisation for Joint Armament Cooperation (OCCAR) is developing the future European MALE UAV on behalf of France, Germany, Spain and Italy. Airbus Defence and Space Gmb, assisted by their major partners, Dassault Aviation, Leonardo, and Space SAU, are producing the future “Eurodrone” which will progressively replace the Reaper drones in France.

More than 80 countries are said to have military drones of all types (surveillance and armed). Over the past two years, more than 15 countries have carried out drone strikes, including Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Iraq and Nigeria.

Innovation driven by use

Although drones originated in the world of defence, the market is now driven by civilian drones, such as the Anafi drone from the French company Parrot. These professional and consumer drones are becoming increasingly powerful. Available “off the shelf”, these low-cost drones (€3,000-€100,000 each) can be adapted for military use, particularly by non-state groups (Hezbollah or Islamic State), for observation missions as well as for armed action.

The dynamism of both the civilian and military markets, the incorporation of technologies developed for civilian use in the fields of security and surveillance (photonics, optronics, AI, image analysis, sensors of all kinds, etc.), but also in transport (autonomy), are leading more and more industrial players, and more and more varied, to invest in this booming industry.

The purely military market and the civilian market are intermingling, in a dual technology approach: the French company Photonis, leader in night vision, offers a camera in the form of a micro-cube that can be grafted onto drones. Its primary market is defence, but it is also very interested in the civilian security market. Rapid evolution of drones is bringing new challenges: their autonomous operation, connectivity, cooperation between drones and robots in heterogeneous swarms, and of course the cybersecurity that is essential to these developments.

A particularly dynamic field, at the crossroads between the civilian and military sectors, is that of countering unmanned aerial systems (CUAS). For example, the DroneControl of the Brazilian company Neger is an integrated system that detects, locates, tracks and blocks hostile drones in secure areas. It is used in Brazil to monitor prisons and prevent gangs from being able to send drugs to prisoners. The DroneBuster from France’s T‑OPS is a portable CUAS tool, the only one of its kind authorised by the US Department of Defence. The BXDD system from Hungary’s BHE Bonn Hungary Electronics is a state-of-the-art solution based on software defined radio to detect, classify and measure the direction of the drone and the RF signal from the remote control. There are also anti-drone guns such as the DroneGun MKIII, a compact and lightweight UAS countermeasure solution designed for one-handed operation.

Combined with miniaturisation, the incorporation of various technologies opens up the range of possibilities in a logic of innovation driven by uses. Thirty years ago, the drone was an unmanned aircraft. In 2021, the US Marine Corps tested the Drone40 from the Australian start-up DefendTex: a tiny drone so named because it can hold a 40 mm grenade and drop it almost 20 km from its operator. The autonomous flying grenade has a GPS-based autopilot system and a portable ground control station that communicates via an encrypted radio link. Drones are military technologies that have been used in the civilian sector before returning to the military, with all the advantages of the civilian sector: optimised by the competition, cheap, easy to handle.