Why energy retrofitting hasn’t taken off

- The building sector is responsible for 28% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, two thirds of which relate exclusively to indirect emissions (heating, lighting, ventilation etc.).

- While the potential for energy retrofitting is currently under-exploited, it is a crucial step towards reducing indirect GHG emissions.

- So far, energy renovation has been slow because there is a lack of both real government action and support from the real estate sector.

- We seem to be moving in the right direction, but it is not yet possible to meet long-term objectives: energy retrofitting must therefore become a new social norm.

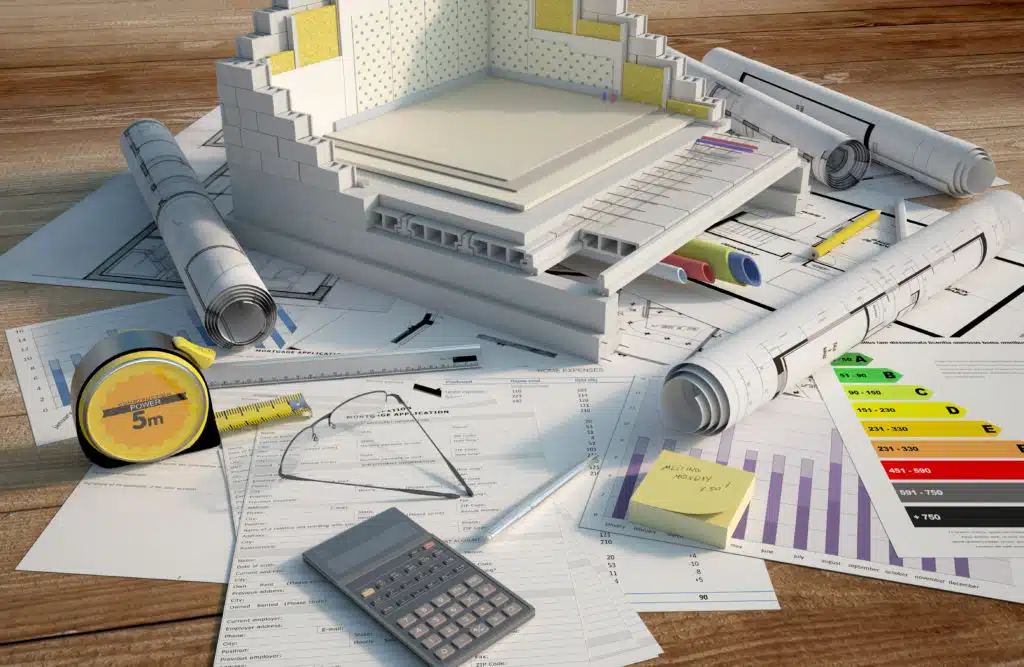

The building sector (residential and non-residential) is responsible for 28% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions1. Although the French average is in line with this figure, the sector accounts for 36% of the European Union’s emissions2. So, what are the principal means of mitigation? Indirect emissions. Heating, domestic hot water, lighting, ventilation, and household appliances account for two thirds of the sector’s emissions. According to Ademe, in France, the sector’s consumption has increased by 20% in 30 years3.

Some countries are now setting targets. Thermal regulations govern the construction of new buildings (the RE2020 is applicable in France, for example). Many retrofitting plans, based on financial aid, aim to improve the thermal insulation and heating of existing buildings. Energy retrofitting is a crucial means of mitigation, but the building renovation rate is only 1.1% in mainland France4. As such, we can see that energy retrofitting is struggling to gain momentum: CO2 emissions from housing energy consumption fell by an average of 2.5% per year between 2012 and 20195, yet 17% of French housing (i.e. 5.2 million dwellings) are energy “sieves”6.

So, how can we speed up energy retrofitting in France? A report published in May 2022 by IDDRI and ADEME7 is based on work carried out by 23 experts, as one of the authors, Andreas Rüdinger, describes in detail.

Why has the implementation of energy retrofitting been so slow?

Everyone agrees on the importance of energy retrofitting, but there has been no real progress, it is in total disarray! In our report carried out in 2020, we identified various sticking points that we call controversies. The most important of these is the difficulty of imposing energy-efficient renovation as a new social norm.

On the household side, for example, there is no label to compare properties on the housing market. The energy performance diagnosis provides useful indicators, but energy performance is far from being a priority in the property market. Real estate professionals also need to recognise this new standard. However, professional federations are still very reluctant to accept energy renovation obligations and the constraints that could result from them and are generally less interested in energy renovation than in new construction.

Don’t public policies have a role to play in developing this new social norm?

Of course. Over the past 10 years, it has become clear that there is no strategic roadmap. Each year, subsidies allocated differently: sometimes towards specific equipment (such as the replacement of boilers), and less towards others (such as double glazing), or towards retrofitting packages, etc. In 2017, a study showed the value of setting up a single-subsidy based on the performance achieved after renovation. The 2019 Energy and Climate Law obliges the State to include a comprehensive plan for energy retrofitting in the next Multiannual Energy Programme, but this has been slow to materialise.

This lack of a coherent leadership is one of the major obstacles to achieving widespread retrofitting. It is impossible to carry out any real transformation of the sector, as companies cannot invest without a medium-term vision. This transformation is however necessary because there is not enough incentive.

Is this a lack of strategic vision or an economic problem?

The second controversy identified is the lack of a strategic roadmap, which generates economic obstacles. Economic analysis of retrofitting suffers from a lack of consistency. How then can we define the scope of the cost of energy retrofitting? For some, it represents the entire cost of the work. But this then includes work that is not related to energy performance because most households carry out more comprehensive renovations than just for that purpose. Other analyses focus on the additional cost directly attributable to the energy performance improvements, excluding maintenance and repair work (e.g. replacing a boiler at the end of its life is not included in the cost of energy renovation).

The same question arises for the benefits obtained: should we only take into account the reduction in energy bills, or should we include the benefits related to comfort and participation in the ecological transition? To overcome this controversy, we propose evaluating not the profitability but the economic viability of renovation. It integrates different criteria: the benefits for households in the broad sense, financial solvency and the reduction of risks linked to efficient retrofitting. This last point remains crucial for building collective confidence around “low energy” renovation.

Efficient retrofitting cannot be a basic renovation resulting in a better performance class than F.

Finally, it should not be forgotten that by tackling the “thermal sieves”, inhabited by low-income households, we are also working towards a fair transition. A large part of the cost of renovation is covered by public finances, but the remaining costs or pre-financing can be a real obstacle. In response to the energy crisis, the French government committed €30 billion to freeze prices and help pay bills: this kind of investment in energy retrofitting would have been significant, but nothing has been done.

Given these findings, how can we speed up energy retrofitting?

We need to make efficient retrofitting a new social norm. The term “efficient renovation” must be more clearly defined and made transparent for industry players, as is the case in Germany. It cannot be a basic renovation that results in a better performance class than F. An efficient retrofit is a comprehensive renovation that ensures the delivery of a “low energy building”.

In order to work towards this goal, subsidies must be accompanied by performance obligations at the end of the work. Today, there is no systematic monitoring of the impact of the subsidies, and one-off works receive more support on a pro-rata basis. This system is not only detrimental to energy performance but also to the monitoring of policies. We have no clear vision of the real effectiveness of the renovations undertaken.

Yet GHG emissions from the building sector are falling. In 2021, they will even remain below the emissions ceiling set by the National Low Carbon Strategy (NLCS): amounting to only 74.9 Mt CO2e, compared to a threshold of 77 Mt CO2e8!

This is certainly a step in the right direction. When we started our study three years ago, the building sector was the one that was furthest behind on its carbon budget. However, it should be noted that the current good results are partly explained by two changes: the sector’s carbon budget was increased in the revision of the SNBC in 2020 (editor’s note: it went from 65.4 to 80 Mt CO2e for 2020) and the method of calculating GHG emissions was changed, shifting part of the emissions to the energy sector.

This downward trend can be explained by short-term gains, such as the massive replacement of boilers. However, these gains will not allow the long-term objectives to be met, in particular the objective of achieving a “low energy building” average performance level for the sector as a whole by 2050.