Immense remaining oil reserves and the challenge of reducing consumption

- Oil, a major contributor to the greenhouse effect, now accounts for 32% of the global energy mix.

- The global economic recovery following the pandemic has increased demand for oil worldwide.

- But there will be no “peak oil”: we have more oil reserves than we need, at 150-160 Gt at its lowest.

- Oil has certain advantages and will continue to be used unless governments take restrictive measures.

- There are several ways to reduce GHG emissions, such as energy sobriety or the development of renewable energies.

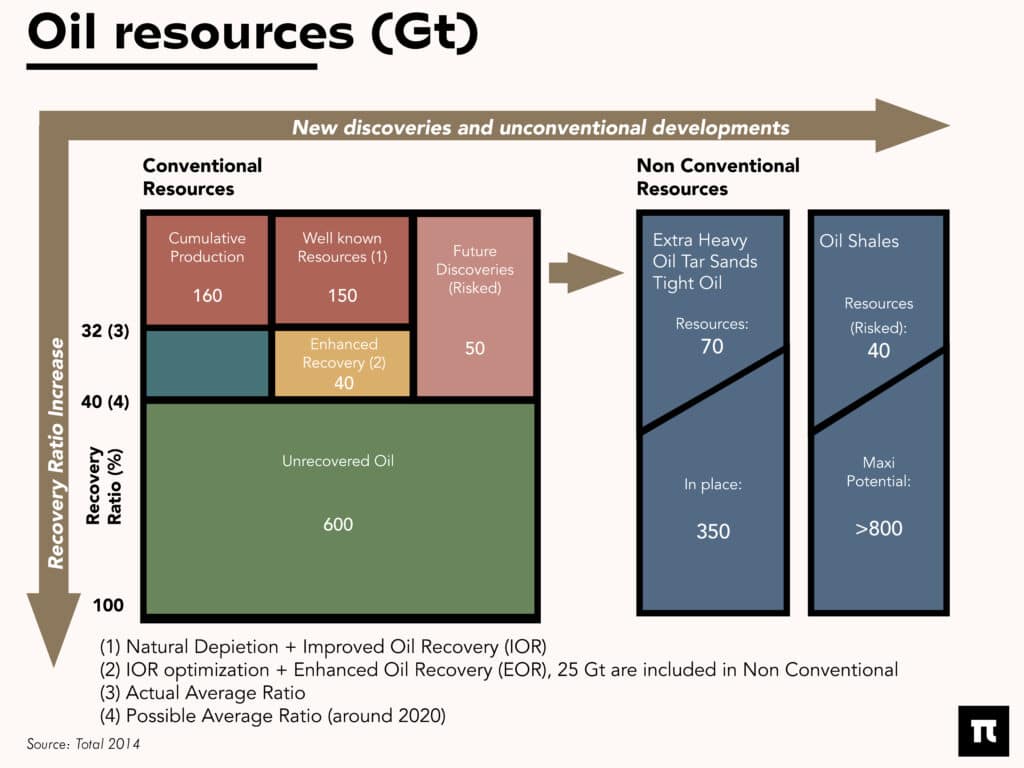

Taking into account the most conservative estimates, the known and quantified volumes of hydrocarbon reserves remaining on Earth today correspond to the total amount we have consumed since the beginning of the oil era (i.e. the end of the 19th Century). This is equivalent to 150–160 Gt1 oil equivalent. These quantities are four times higher if we consider the stocks that have not yet been precisely quantified (600 Gt), although some of these resources may be difficult to exploit for geological, economic, or geopolitical reasons. According to a new report2 , the world’s fossil fuel reserves contain the equivalent of 3,500 billion tonnes of greenhouse gases (GHGs). These gases, if released, would jeopardise international climate targets3 .

The inventory, which contains data on more than 50,000 sites in nearly 90 countries, is used to provide the information needed to manage the phase-out of fossil fuels. In particular, it shows that the US and Russia each hold enough reserves to blow the entire global carbon budget, even if all other countries stopped production immediately. It also finds that the world’s most powerful source of emissions is in the Ghawar oil field in Saudi Arabia.

Peak oil will not happen

“We grew up with the idea of peak oil, thinking that there would be an inevitable shortage by 2010–2020,” explains Antoine Le Solleuz. “This notion no longer exists, because oil companies have invested so much in hydrocarbon exploration that they discover new deposits every year. We are now in a situation where possible oil reserves exceed consumption.”

We are now in a situation where possible oil reserves exceed consumption.

“The notion of peak oil results from the notion of oil reserves,” adds Olivier Gantois. “What is announced as oil reserves at any given time are the volumes of oil that have been identified and that we know how to produce with today’s technologies and at today’s prices. The price of a barrel is $85, but if we have a part of the reserves that costs $100/barrel to produce, we don’t count it as reserves because it is not economic. This means that if tomorrow we have the same quantities of hydrocarbons, but the price of a barrel rises to $120 barrel (as was the case last July), these volumes can then be counted as part of the reserves.”

These sources of oil are classified as conventional or unconventional. In conventional sources, the oil in the bedrock migrates to a permeable reservoir, from which it can then be extracted relatively easily.

Unconventional sources are different in that the reserve is either contained in a virtually impermeable reservoir or in the bedrock itself, from which it must be extracted – which is technically more difficult. The discovery of unconventional deposits, the best known of which is shale gas, has quadrupled in recent years compared to the beginning of the century, and these sources have even become the norm in some countries. Indeed, they have enabled countries such as the United States to become energy independent, allowing them to disengage from the conflicts in the Middle East.

In addition to the US, unconventional deposits have also been discovered in Canada, France, the UK, Poland, Russia, and Algeria, to name a few. France has decided not to exploit these deposits, unlike other European countries. It should be noted that non-conventional deposits involve the use of techniques such as hydraulic fracturing, which is currently prohibited by law4 .

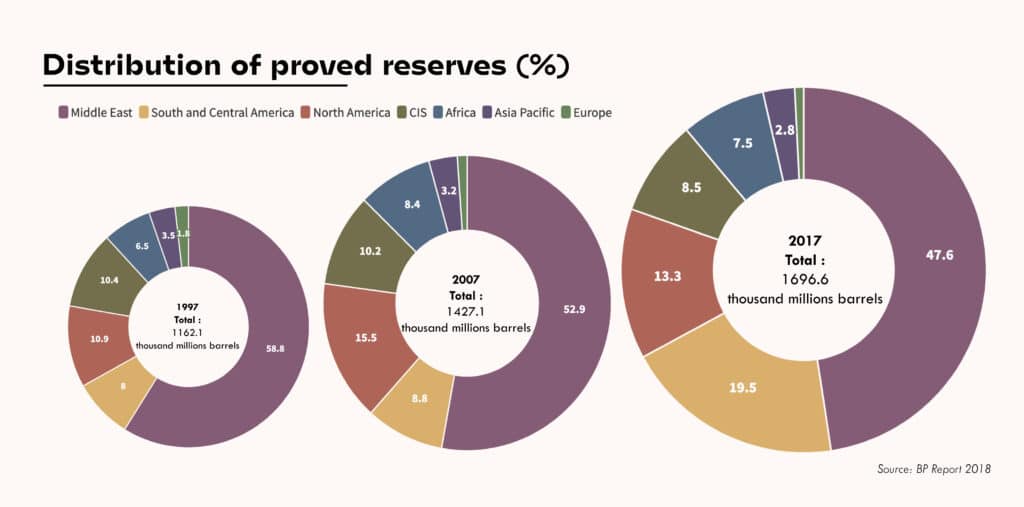

The danger of incorrect estimates

“There are possible reserves (90% uncertainty), probable reserves (50% uncertainty) and proven reserves (10% uncertainty),” says Antoine Le Solleuz. “Venezuela, for example, is still considered to have the largest estimated reserves, although this cannot be confirmed by other countries as the estimates are published by the Venezuelan authorities themselves. There are also countries that are self-sufficient and have refused to involve large private energy companies such as BP, Shell, Total and Exxon. This allows them to estimate their own reserves, which also frees them from the stock market and other economic systems. This is the case in Saudi Arabia, for example, where only the national company, Saudi Aramco, is allowed to operate.”

However, a country’s estimates can be “incorrect” – intentionally or unintentionally – which can create instabilities in the stock markets because other countries cannot compare themselves and thus set a realistic price. To gain the confidence of investors, major oil companies publish their own estimates: if they under- or overestimate their reserves, they suffer direct consequences on the financial markets.

BP and Shell, for example, faced scandals of overestimating their proven reserves in conventional reservoirs. As a result, the financial markets lost confidence in these companies. However, this financial and scientific confidence is essential, as it is the key to sustaining financial investments in exploration and production. These investments are becoming increasingly important over time, using more and more sophisticated geophysical techniques, more and more complex wells, in more and more extreme geological contexts.

“We cannot (and should not) answer the question of reserves in terms of number of years if we continue to consume at the same rate as today,” maintains Antoine Le Solleuz. “Because the more we invest, the more we find. And the oil companies continue to invest.”

Our current economy is heavily dependent on it, but oil is a major contributor to greenhouse gas emissions. Today, it accounts for 32% of the global energy mix5. To meet the commitments of the Paris Agreement and reduce GHG emissions by 45% by 2030 (compared to 2010 levels), we need to gradually reduce our use of oil in favour of decarbonised energy.

Regulation is needed

France aims to establish a sustainable energy model, thanks to the 2015 Energy Transition Act6 and an investment of more than five billion euros per year in renewable energies, by diversifying the energy mix: fossil fuels should be reduced by 30% by 2030 (compared to 2012). The energy-climate law of 8th November 2019 has even set a new, even more ambitious target of 40%.

Other measures affect production, and France has adopted two laws concerning the exploitation of hydrocarbons. The first one bans outright the exploration and exploitation of non-conventional hydrocarbon mines by hydraulic fracturing. The second puts an end to the exploration and exploitation of hydrocarbons by 2040.

Consumers will continue to use oil if restrictive measures are not put in place by the government.

The global economic recovery following the Covid-19 pandemic is increasing the level of demand for oil, which had fallen significantly during the period when restrictions were put in place to contain the spread of the virus. Demand has almost returned to its pre-crisis level (100 million barrels per day), which is reflected in the price of Brent crude oil today.

The growth in demand must be controlled to control GHG emissions, according to the IEA which published a report in June 20217. The measures advocated in the report include the introduction of a new energy model based on renewable energy and nuclear power.

“The problem that we are facing today is that oil and oil products have many advantages,” explains Olivier Gantois. “They are concentrated forms of energy, so they are easy to transport and store. Consumers will therefore continue to use oil and possibly even more of it if restrictive measures are not put in place by public authorities.”

The EU has decided to ban the sale of internal combustion engine vehicles from 2035.

An example: a few weeks ago, the EU decided to ban the sale of internal combustion engine vehicles, those using liquid fuels, from 2035. Only decisions like this will reduce the use of liquid fuel for road transport. However, it will take some time to see the effects of this measure: in France, we have about 45 million vehicles on the road, and new vehicles account for only 2 million per year.

“As we like to put it, there are five main ways to reduce GHG emissions: Not consuming energy (commonly referred to as energy sobriety); using energy more efficiently; developing renewable energies that do not emit GHGs; decarbonising liquid energies (producing them from waste, or biomass); the circular economy – i.e. reusing everything that can be reused (plastics that we use directly, carbon emissions that we recover to make synthetic fuels…). Each of these five dynamics will lead to a reduction in oil consumption and thus in GHG emissions into the atmosphere.”