Will there be a “post-covid” economy?

We are all wondering what the pandemic will change in the long term. Will the Covid-19 health crisis leave a long-lasting trace in our economic system? Its a question we still cannot answer with certainty because it is difficult to assess what structural ruptures will remain after the crisis is over. However, we can see at least six possible disruptions in the fields of the labour market, industry, energy transition and digitalisation, as well as monetary and fiscal policies. At this stage, these are only trends and weak signals, so only time will tell if they come to pass.

- Labour market: fewer applicants and higher wages?

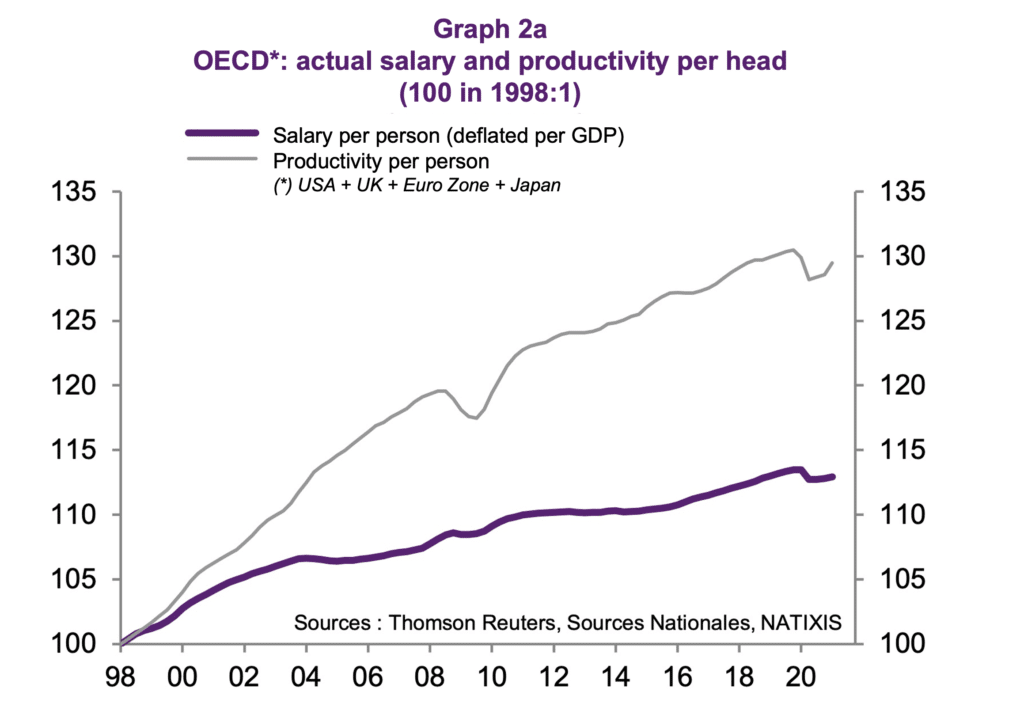

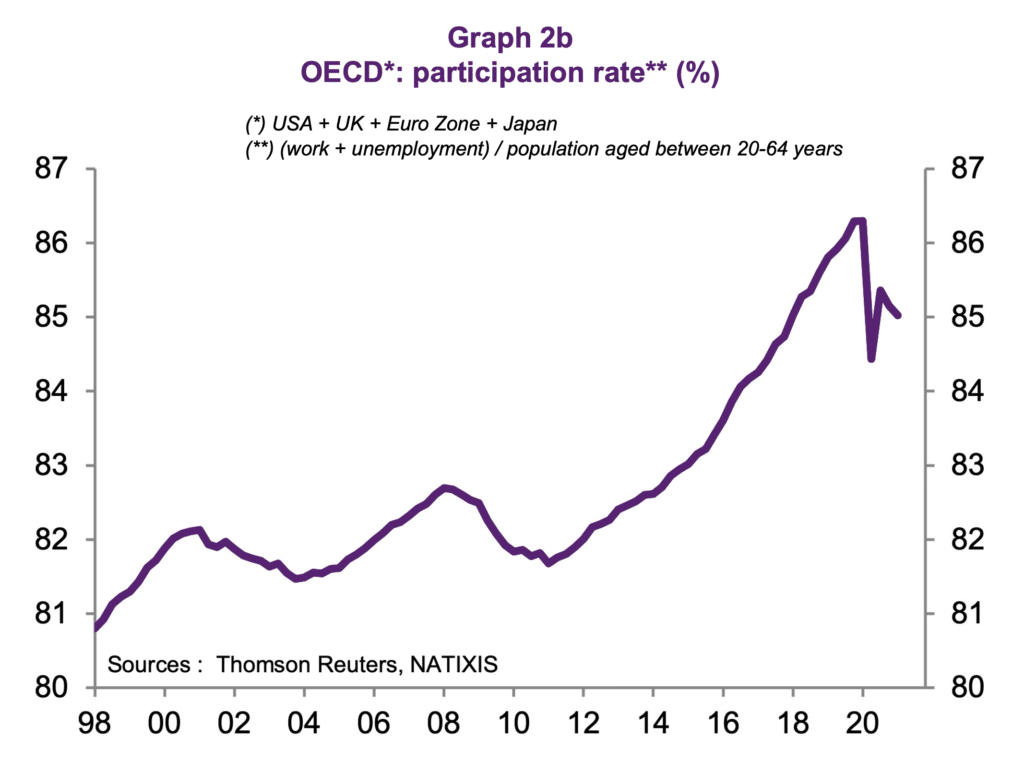

Since the late 1990s, OECD countries have experienced a distortion of the income distribution to the detriment of employees. There has been a decline in employee bargaining power with companies they work for (Figure 2A). However, since the beginning of the health crisis, there has been a decline in participation rate, i.e. the proportion of working-age people entering the labour market has fallen (Figure 2B). If this trend were to continue or increase, the rising tension on the labour market would be favourable to employees and wages would rise, thus generating some inflation.

2. Will industries recover?

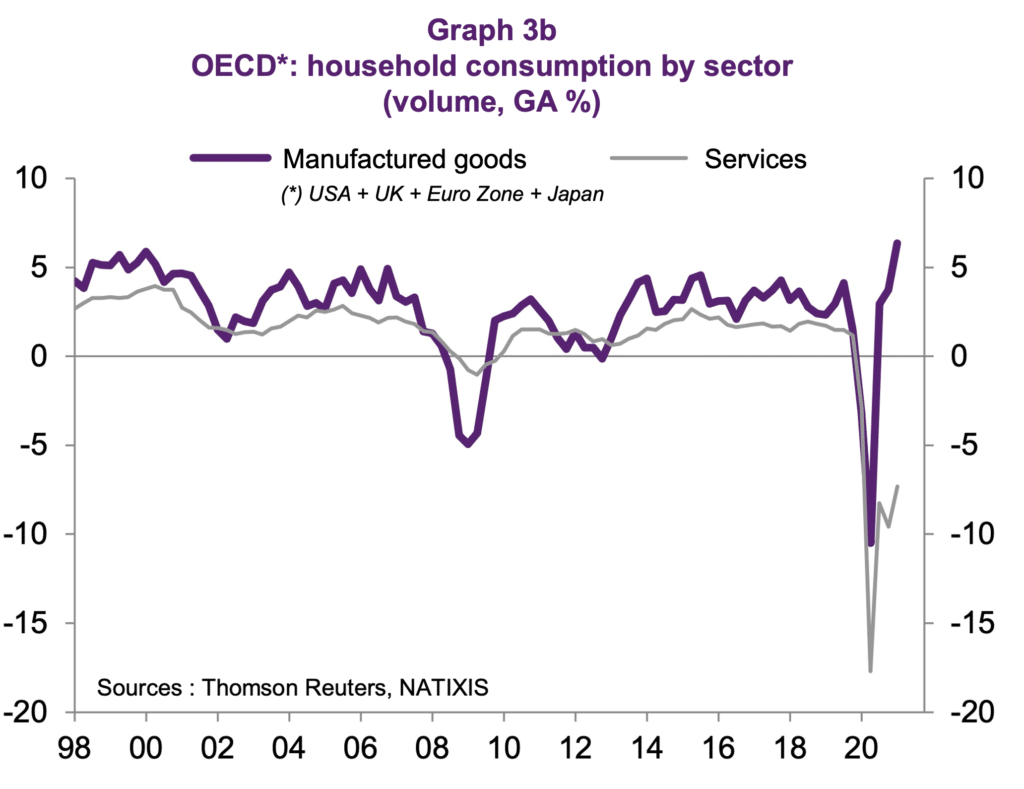

For more than twenty years, the amount of production by advanced economies has been on the decline. However, since the beginning of the Covid crisis, we have seen a drop in the consumption of services due to health restrictions (restaurants, leisure activities, etc) accompanied by a sharp rise in the consumption of goods. This is linked to the development of online commerce and different needs or desires that emerged during the lockdowns (gardening, decoration, creative leisure activities, etc.). In the face of this, will industry recovery (graph 3B)? Yes, there is reason to believe so thanks to the new needs linked to working from home (electronics, furniture), the need for equipment for renewable energies (wind turbines, electrolysers for hydrogen) and because of government recovery plans and investments in infrastructure. Will this create jobs in OECD countries? It could be the case, if some production is relocated for reasons of sovereignty or to simplify the supply chain (medicines, high-end textiles) this would increase the need for skilled workers.

3. What will be the consequences of acceleration in the energy transition?

The pandemic has contributed to accelerating the energy transition, but it is not yet clear what the consequences of a rapid transition to net zero CO2 emissions in 2050 would be. Will the jobs destroyed (car industry, oil sector) be replaced by others (thermal insulation, wind farms)? Will renewable energy equipment be manufactured in OECD countries or imported? For the moment, the share of the these products manufactured in France is very low. The second option – import – would lead to a decrease in added value for these economies. And finally, what effect will the energy transition have on the price of energy? The intermittency of renewable energy production will likely mean a sharp increase in price because of the need for electricity storage.

4. Is digitalisation positive for the economy?

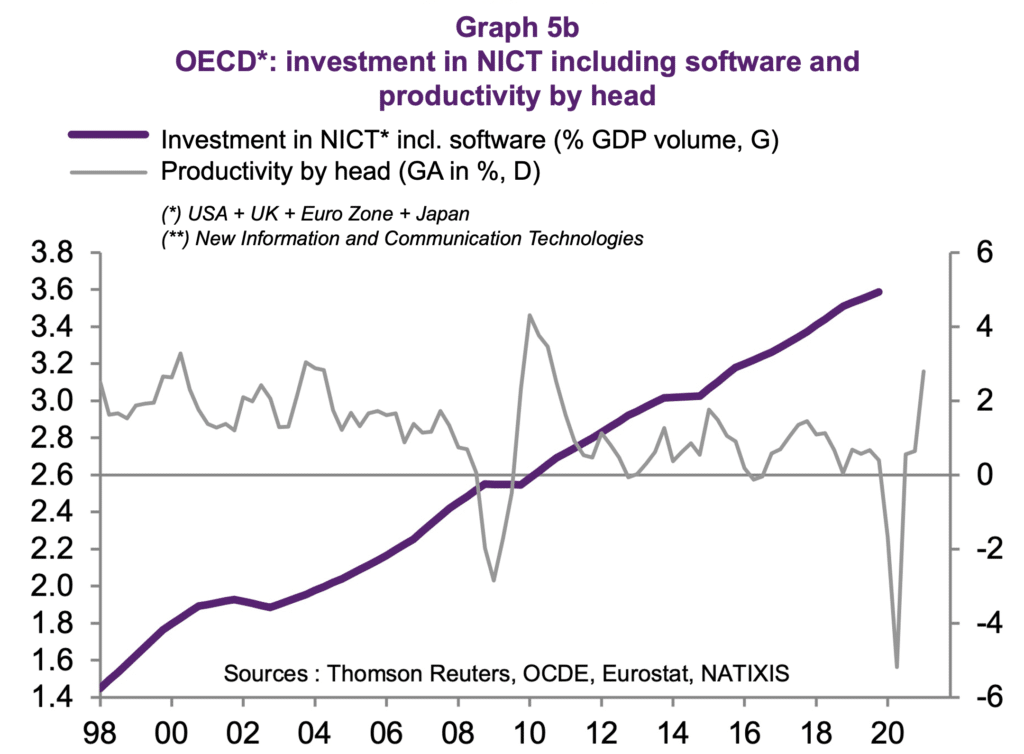

Nothing is less certain. Digitalisation of the economy has accelerated since the beginning of the pandemic (e‑commerce, deliveries). However, while digital technology creates highly skilled jobs in the design of services (computer developers, engineers), it also creates a large number of unskilled jobs (delivery personnel, packers). This polarisation results in strong income inequalities. Moreover, it is not at all certain that the digital economy increases productivity. On the contrary, it has been observed over the past 20 years that the increase in investment in new technologies has coincided with a slowdown in productivity (Figure 5B).

5. Can central banks change their policies?

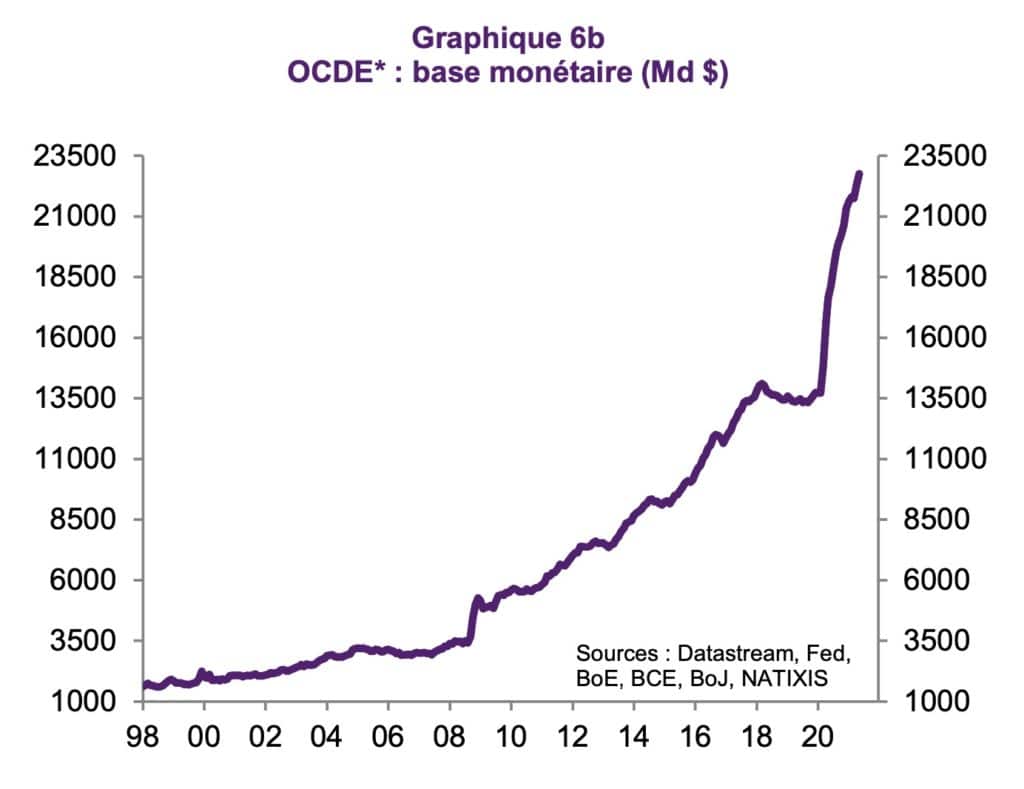

The “whatever the cost” approach to saving companies and jobs by the government has required the intervention of central bankers. In doing so, they have monetised state debt by greatly increasing the volume of money in circulation i.e. printing banknotes. Contrary to widespread belief, governments will not have to repay a large part of the debts they have contracted, as these are now recorded as liabilities of the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Federal Reserve, and it is difficult to see why this option should change (Figure 6B). On the other hand, if monetary policy has made it possible to maintain the solvency of states, it has strong repercussions on asset prices. The availability of liquidity results in higher asset prices (real estate and corporate values) which increase wealth inequality (Graph 6B). On the other hand, it is not clear whether a rise in interest rates would lead to a public debt crisis.

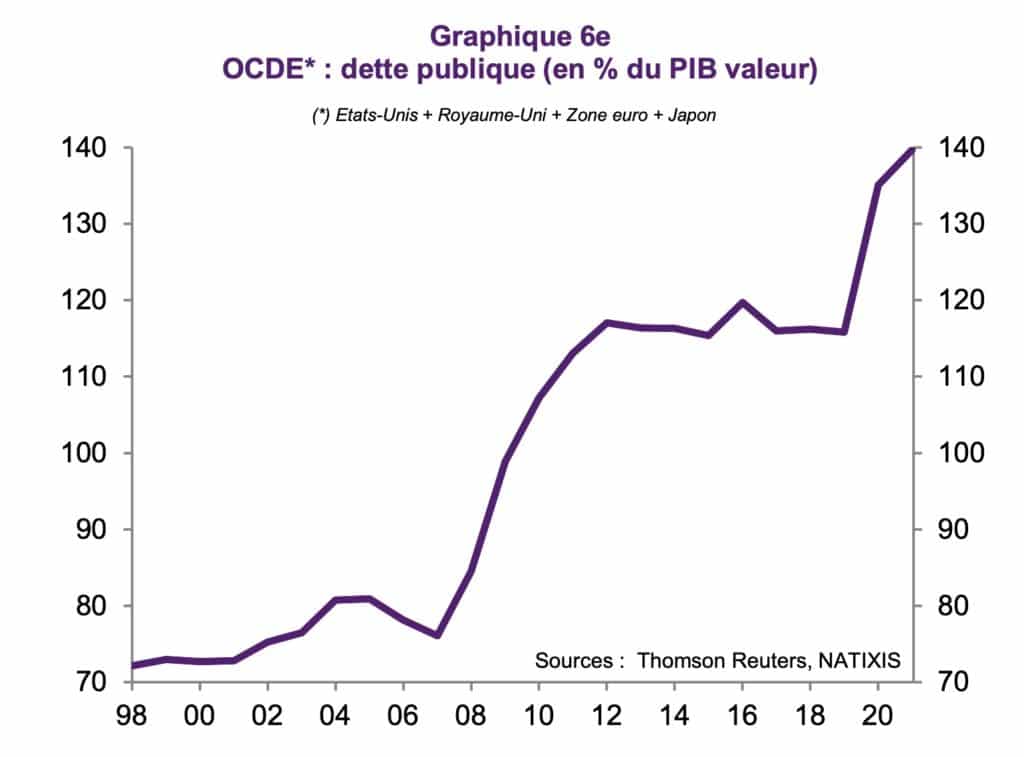

6. Can states forego public deficits?

The health crisis has required huge mobilisation of liquidity and governments have really pushed the usual limits of deficits and public debt (Graph 6E). Public opinion has become all the more accustomed to these increases because of the growing number of needs: energy transition, relocation, health, research, young people, the fight against poverty. In France, for example, there are several announcements per week that require an increase in public debt (investments in Marseille, reimbursement of psychology consultations, commitment income for young people). Will states be able to return to more sobriety? We don’t know, but we do know that if they don’t, the pressure on central banks to maintain their accommodating policies will be considerable.