Will the pandemic trap economies in secular stagnation?

[This article is a summary of an in-depth analysis published at variances.eu, for the original article click here]

It is a rare event: in 2020, economic activity in the developed world fell by 5.3%. As such, the Covid-19 crisis could trap economies in “secular stagnation”, a prolonged period of sluggish growth. Three factors support this hypothesis: a decline in potential output, changes in household and business behaviour, and the acceleration of the digital transition, which is a major factor in inequality.

History shows that deep recessions often have lasting consequences on the main macroeconomic variables (GDP, productivity, unemployment), even after the initial shock has fully dissipated. This is known as “hysteresis”: the phenomenon that caused the crisis (in this case the pandemic) disappears, but the crisis continues in the long term.

This hysteresis effect will play a particularly important role in the case of workers who have been thrown out of work by numerous bankruptcies. If the working population has been spared the virus, which mainly affects older people, then mass redundancies could result in a loss of employability of workers, who would then struggle to find a job after the crisis. But the adverse effects will also affect physical capital accumulation and productivity.

The effective lower bound on rates

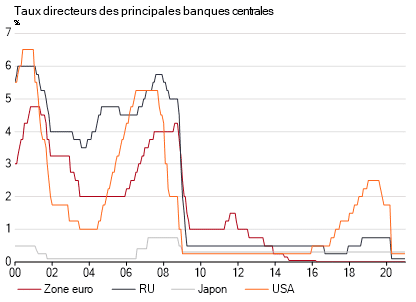

Many developed economies entered this crisis in a vulnerable state, with historically low interest rates and huge debt burdens. Since the subprime mortgage crisis, central banks lowered policy rates to almost zero and resorted to unconventional policies (notably quantitative easing). But this did not translate into a satisfactory recovery in activity.

The economic rebounds were moderate and temporary, while underlying inflation remained stubbornly low, long-term interest rates continued their downward trend, and stock market valuations rose. Overall, monetary policy since 2008 has paved the way for the accumulation of financial vulnerabilities – exploding leverage, excessive risk-taking, asset bubbles – without providing a sustainable boost to activity. And the Covid-19 crisis threatens to accentuate this dynamic. The central banks are now cornered: it is impossible for them to continue lowering their rates.

The interest rate that central bankers seek to achieve is the ‘natural’ interest rate – the theoretical real interest rate at which the economy is neither inflationary overheating nor deflationary depression. It is estimated that this rate has fallen over the last few decades to the point where it is close to zero, making conventional monetary policies ineffective. The explanation for this decline lies in the imbalance between too much saving and too little investment.

The current excess of savings is partly due to the increase in inequalities – the marginal propensity to save of the most fortunate being clearly higher than that of the least fortunate – but also to the efforts to reduce debt made since 2008, as well as to the ageing population (older people having a greater tendency to save in anticipation of their retirement). The fall in business investment is, for its part, mainly a consequence of the weakening of growth potential, synonymous with a decline in future real returns on investment.

The secular stagnation hypothesis assumes that central bank policy rates will remain so low that central banks will frequently be unable to reduce them sufficiently to combat recessions effectively. Constrained by the effective lower bound on rates, the economy can only move towards full employment if governments increase the government deficit or if monetary policy becomes highly expansionary, encouraging the distribution of credit and the rise in asset prices that become the engine of growth.

An economy suffering from secular stagnation is not going to remain permanently stagnant. But the underpinnings of growth – the inflating debt and asset price bubbles – increase the economy’s vulnerability to crises. Decline in activity due to crises become stronger and longer than recoveries, mechanically lowering average GDP growth.

Risk aversion

The Covid-19 crisis is likely to aggravate the problem of excess savings. One reason for this is that “extreme” risk events – also known as “black swans” in the financial sector – often lead to a challenge to old belief systems. As economists have pointed out, “The greatest economic cost of the Covid-19 pandemic may be the result of behavioural changes that persist long after the immediate resolution of the health crisis 1.”

The seismic shock of the pandemic could result in a structural increase in risk aversion of firms and households, leading to a reduction in their investment and consumption spending, in order to build up a larger savings cushion for future crises. A fall in consumption, which means fewer opportunities for companies, generally results in a fall in investment. Moreover, the inclusion of epidemiological risk is likely to increase the risk premium required to justify certain productive investments, further curbing the accumulation of physical capital.

Increasing inequality and the digital revolution

Covid-19 could also contribute to secular stagnation by exacerbating socio-economic inequalities. The sectors most affected by the current crisis are those employing an irregular workforce (such as the hotel industry). But the exponential development of the digital economy since the beginning of the pandemic is also a vector of inequality, for two main reasons: it favours highly qualified workers (this is known as « skill-biased technological change »), and leads to the robotisation of routine tasks, which were mainly carried out by low- or medium-skilled labour.

However, as the most affluent are those with the highest propensity to save, the phenomenon of excess private savings at the origin of the fall in the natural rate of interest should become even worse.

Nevertheless, secular stagnation is not an evil without a remedy: fiscal policy has an important role to play in its resolution, by absorbing excess private savings via an increase in public deficits 2. Moreover, the digital transformation could result, as some predict, in a productivity boom that would boost economic growth.