Why the European Central Bank wants to digitize the euro

[Summary of an article from variances.eu.]

In mid-2021, the European Central Bank (ECB) is expected to announce a project for a digital euro to be implemented within the next 5 years. The United States could follow with their “digital dollar”, but this will be later. There is already a lot of talk about this Central Bank Digital Currency project. In simple terms: what will this digital euro be, why is the ECB interested in it and how will it be implemented?

What is a Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC)?

As a reminder, only physical cash – coins and banknotes –, called “fiduciary” money, are issued by the sovereign authority and are legal tender in a country meaning they cannot be refused in payment. So-called “scriptural” money (partly made up of bank deposits) is created by supervised and regulated banks and can be transferred electronically. These two forms – fiduciary and non-cash – together perform the three functions of money: unit of account, means of payment and store of value (provided that inflation remains low).

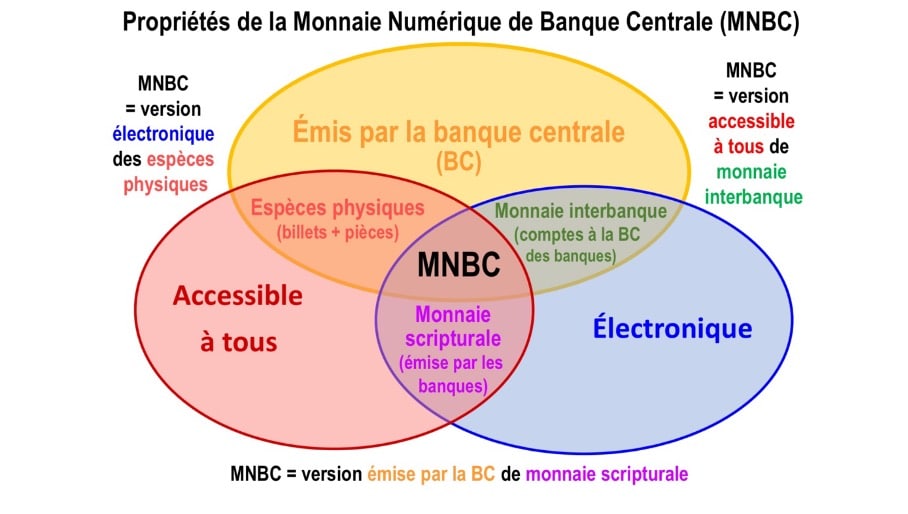

As such, a CBDC combines the advantages of these two forms of money. (1) It represents a claim on the central bank that is as secure as a banknote (and therefore more secure than a bank deposit); (2) It is accessible to everyone, like a banknote (whereas currently only banks have an account with the central bank); (3) But it is electronic and can be used remotely (unlike a banknote). It is thus at the heart of the diagram below.

How would the digital euro differ from Diem or Bitcoin?

CBDC should not be confused with “stablecoins”, electronic assets that are starting to be produced by the private sector but are indexed to existing currencies. The best-known example of these stablecoins remains the Diem, initially named Libra by Facebook as early as 2019, but still in the pipeline. Stablecoins, issued by unsupervised entities, pose risks to monetary and financial stability (data protection, potential global oligopolies, etc.).

CBDC also differs from crypto-assets (mistakenly called “cryptocurrencies”), whose value is not based on any existing currency. The value of Bitcoin, the most famous example, is extraordinarily volatile because it is based on its announced scarcity (at most 21 million units) and its increasing economic and environmental production costs. Thus, one Bitcoin transaction currently consumes the energy needed for half a million transactions per card. This also limits its scalability, which is essential for a currency. Nevertheless, crypto-assets are in demand as speculative assets, which need to be regulated 1.

Why digitize money?

On the one hand, to maintain public control over money creation in the face of private competition. The CBDC provides a complement to banknotes, whose use for transactions is decreasing (in volume and in value) but whose issued stock is increasing (hoarding). It is a question of proposing a monetary asset guaranteed by the State in an uncertain digitized world. Money is a public good, and the central bank must offer a risk-free alternative to digitized assets issued by unsupervised private entities. There is also a geopolitical dimension: foreign digital currencies (public or private) risk destabilizing, if not crowding out, national currencies, as in the case of the « dollarization » of developing economies.

How to design a digital currency?

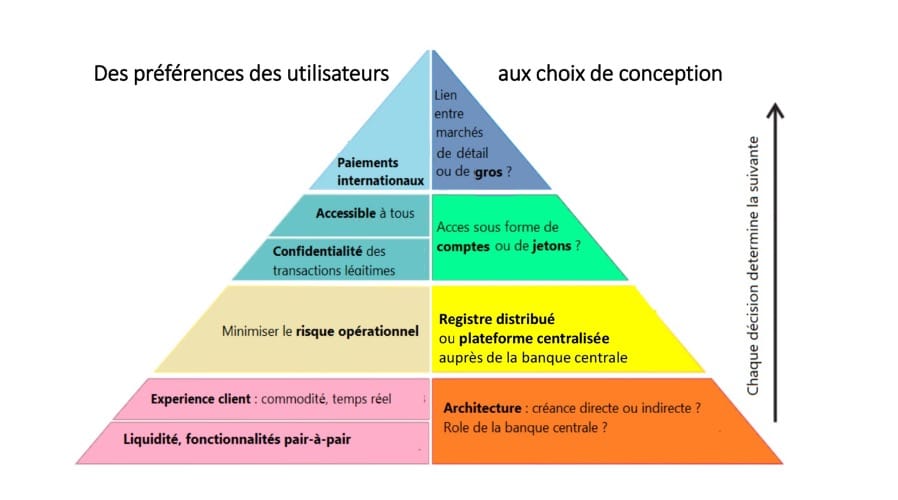

Between now and the actual digitization of the euro, various choices still need to be made, notably concerning the scope of the public-private partnership, the balance between confidentiality and compliance, and the legal framework. Trust in the currency is at stake.

The ECB will probably opt for a hybrid architecture (red base of the pyramid): it will not fully delegate the management of the digitized euro to the private sector but will not directly manage it either. In its 2020 report, it thus explains that “supervised private intermediaries would be best placed to provide ancillary services” and that “a model in which access to the digital euro is intermediated by the private sector is therefore preferable”.

The ECB must also decide on the issue of the technical infrastructure (yellow level). This could be centralized on a single platform or use a distributed ledger via a decentralized network of computers, which may pose a scalability problem.

The green level corresponds, in particular, to the trade-off between privacy protection, favoured by the choice of a token (like a bearer bill), and regulatory compliance; the latter could require an account to trace transactions, in particular to avoid money laundering or terrorist financing.

The tip (blue) of the pyramid refers to interoperability, i.e. the ability of the CBDC to link wholesale and retail markets by being connected to national and cross-border payment systems. Thus, the banknotes are specific to each currency zone, but respect global standards allowing them to be exchanged.

Finally, and in addition to various technical aspects (cyber risks, offline transactions, etc.), legal considerations need to be clarified. These include: the legal basis for digital issuance, the legal implications of different formats, and the applicability of currency zone laws to the central bank as issuer. Without going into detail, a combination of articles in the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union and the Statute of the European System of Central Banks should make this possible, according to the ECB 2020 Report.

Innovations have marked the history of currencies. An MNBC will be another great step in the “Cash Odyssey”. The need for central banks to accelerate the ongoing process is clear, especially in partnership with the private sector. From crypto-assets or stablecoins to MNBC projects like the digital euro, a general principle always seems to apply: “the private initiates, the state regulates or appropriates”.