Say on Climate: the influential role of shareholders in company policies

- Say on Climate is a resolution on a company's climate strategy that is put to a shareholder vote at a general meeting.

- In the event of major controversy, shareholders can threaten legal action or take legal action against companies whose policies they disapprove of.

- Many companies submit Say on Climate resolutions purely as a formality and without any real ambition: they are more likely to be greenwashing.

- The lack of clarity regarding the authority of stakeholders in Say on Climate resolutions has led to tensions in climate-related discussions.

- Stakeholder policies and initiatives could help to improve Say on Climate

Shareholder general meetings are a key moment of shareholder democracy – particularly for listed companies. Indeed, it is when shareholders are usually consulted on a range of vital subjects: elections for the board of directors, remuneration of the executives or the modification of the company’s statutes. Under certain conditions, they can also propose resolutions to be voted on, such as essential climate policies. It is in this context that the Say on Climate model has appeared.

Shareholders can influence climate policy

Designed on the model of Say on Pay, which concerns the remuneration of executives, it was born in the United States and is spreading in Europe, now in France. A resolution on the agenda of general meetings, Say on Climate can be tabled by the company itself – or by its shareholders – to have shareholders vote each year on the climate policy of listed companies and thus ensure a permanent dialogue on environmental issues.

As early as 2009, Ceres (Coalition for Environmentally Responsible Economies, an NGO specializing in sustainable development) and several major institutional investors sent a petition to the American financial authority, the Security Exchange Commission (SEC), asking them to require companies to be more transparent about their climate impacts and carbon footprint.

In January 2019, 30 current and former Amazon employees who held bonus shares filed a resolution for Amazon to present a climate action plan. A few weeks later, in April 2019, more than 6,000 U.S. Amazon employees sent a letter to their CEO, Jeff Bezos, in support of this move.

In December 2017, the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPers), America’s largest public pension fund (1.6 million Californians), launched Climate Action 100+. This initiative brings together investors who are engaging with climate-critical companies, those representing two-thirds of global greenhouse gas emissions, to take the necessary steps to combat climate change. Of these some 166 companies are Air France, KLM, Airbus, Arcelormittal, Pepsi, and TotalEnergies1.

This is what we call shareholder engagement

Well developed in the United States, these filings are often made following an unsuccessful dialogue with the company’s management. Dialogue with companies and tabling of draft resolutions presuppose holding a significant proportion of capital, to have influence over companies or in the general meeting. In general, regulations set a minimum threshold of shares to propose resolutions. In France, this threshold is 5% of shares for SARL / SA, in the United States it is sufficient to have $2,000 worth of shares.

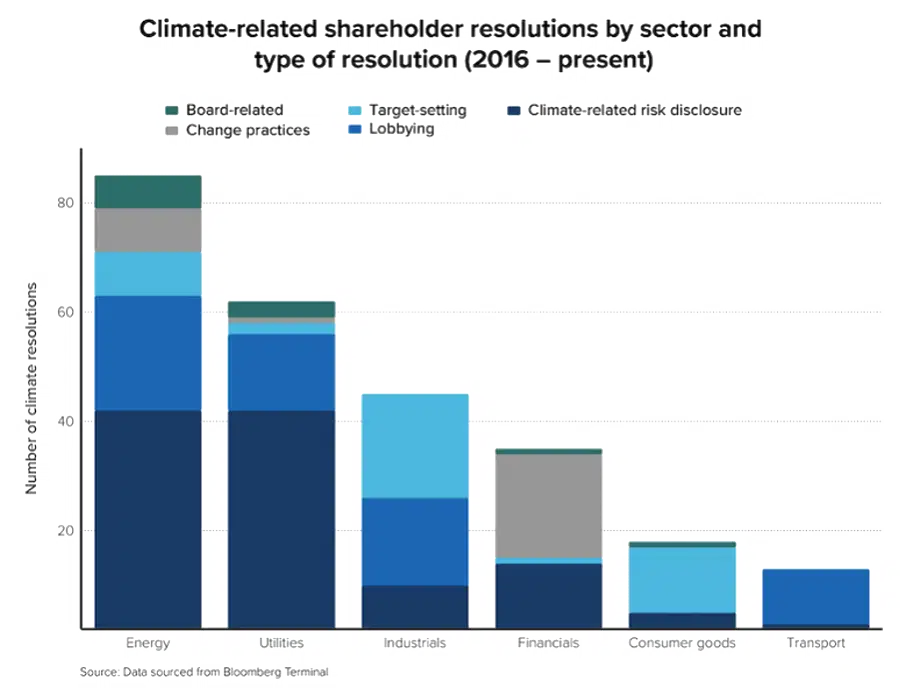

In the United States, external resolutions were mainly related to governance, in particular executive compensation before the adoption of Say on Pay. For the past 10 years, however, ESG issues have represented most external resolutions. Environmental resolutions, especially climate resolutions, are now as numerous as governance resolutions. This is likely due to US environmental regulations being less restrictive; hence, shareholders substitute for the state. To date, the vote on Say on Climate resolutions is purely consultative. Also, in the absence of any legal framework, opinions given are not legally binding.

In France, the majority of external resolutions concern governance issues (appointment of directors, executive compensation, etc.). The first case observed of a climate resolution was TotalEnergies, in 2020, with a draft amendment to the articles of association providing for the company to set category 1, 2 and 3 emission reductions in the medium and long term in application of the Paris Climate Agreements2.

European companies on board

The Share Association lists a total of eleven climate resolutions in Europe in 2020: six in Norway, four in the UK, and one in France. With the exception of Barclays, they all target oil companies. While these remain isolated cases, they are increasing in number. As compared to less than two cases per year on average before 2015, there were five between 2015 and 2019.

Ten French companies took part in the Say on Climate test in 2022, namely Amundi, Carrefour, EDF, Elis, Engie, Getlink, Icade, Mercialys, Nexity and TotalEnergies3. The average approval rate of climate plans put forth for these ten companies was 93%. According to the FIR, these results underline “progress in harmonising reporting with precise criteria and indicators”.

The rate of approval of resolutions rose to 37% for resolutions not approved by the Board (resolutions approved by the Board are over 98%). The identity of promoters has also changed; alongside associations or NGOs, we are now seeing more institutional investors. Climate-related resolutions can be classified into two categories: those that require more information on climateobjectives and the corresponding means implemented, and those that guide the operations.

In the most controversial situations, shareholders or groups of shareholders may threaten legal action, or sue companies whose policies they disapprove of. In the case of climate risks, the plaintiffs are most often NGOs or cities — direct victims of the consequences of climate change — and rarely shareholders. One example was the condemnation of the French state for climate inaction in 2021 by the administrative court of Paris. This followed actions taken in 2019 by Greenpeace, Oxfam, the Nicolas Hulot Foundation and Notre Affaire à Tous.

Still, there are cases of companies being sued by investors for lack of transparency on climate risk. For example, in August 2017, shareholders filed a lawsuit against the Commonwealth Bank of Australia for failing to disclose, in their 2016 annual report, climate risk related to the financing of a coal mine in Queensland.

Say on Climate and regulation

Despite socially responsible investment becoming a widespread issue for shareholders who care to shield themselves from climate-related risks or reputational damage, ESG regulation is further driving this momentum. In Europe, a suite of recent announcements of legislative directives on sustainability disclosures may help increase not only the quantity, but the quality of Say on Climate resolutions.

While the ambition to fight against the negative effects of climate change is easy to state, its implementation is more complex to define, raises concerns, and feed legitimate doubts. In concrete terms, what new practices should be implemented? How can ambition become proven action? Looking at the climate pledges of companies, many are insufficiently defined. Sometimes, poor action plans are not a consequence of intentional maladaptation but rather, lack of knowledge and the resources to verify impact.

Numerous companies have merely submitted Say on Climate resolutions as a formality.

This is also true for Say on Climate filings, where the subject may vary according to issuers, for example, one establishing an energy transition plan while the other considering climate policies for the first time. The consequence of this is a higher likelihood of Greenwashing, where numerous companies have merely submitted Say on Climate resolutions as a formality, lacking transparent plans, concrete strategies, or sufficient ambition. While it is understood that establishing a meaningful climate strategy is difficult, especially the first time, climate resolutions must ultimately lead to measurable, and science-aligned action.

Therefore, sustaining shareholder engagement is essential, so that companies’ climate ambition and the disclosure of executives may be analysed and revised on a regular basis. Yet, according to MSCI, most Say on Climate votes in 2021 (58%) were one-time events, with only 24% of votes set to have annual follow-ups4. So, how to ensure climate action and not merely investor distraction? Policy actions and further stakeholder initiatives could improve the outcomes of Say on Climate.

How will these policies interact with Say on Climate?

Given the reporting mandates as part of the European Green Deal in 2021, and increasing access to ESG data, it is expected that shareholders will become more vocal and stringent in requisitioning Say on Climate resolutions. Already, in France there has been a call to Autorité des marchés financiers (AMF) to mandate all companies subject to the CSRD to be required to Say on Climate5. Companies, too, will benefit from having already collected much of their ESG data to comply with regulation, and be empowered to put forth material Say on Climate proposals.

With the introduction of sustainable taxonomies, shareholders and managers can use a standardized framework to identify environmentally focused activities. This will enable them to communicate effectively using a shared terminology and ensure alignment in their objectives. Lastly, the requirements of mandatory sustainability disclosures should inform Say on Climateresolutions and translate into good practice for company climate plans, for example, incorporating indirect emissions (scope 2 and 3) and ensuring science based target and transition paths.

The future of Say on Climate

As Say on Climate gains momentum in Europe, it is necessary for economic actors to continue to work on improving the nature of climate-related discourse and resolutions, and ensure it does not become a fashionable exercise without substance.

Some stakeholders advocate for providing a legal framework on Say on Climate, to improve outcomes of resolutions. Since Say on Climate is first and foremost, a private initiative and not a regulatory mandate, any framework should focus on delegating the duties of Say on Climate and outlining how motions originating from company management, board of directors, or shareholders should be treated. Currently, the absence of clarity and varying interpretations regarding the extent of each stakeholder’s authority in Say on Climate resolutions has resulted in tensions and conflicts within climate-related discussions.

Nevertheless, policy actions, such as the initiatives of the EU Sustainable Finance Framework, should support and positively interact with shareholder engagement. By providing guidelines to companies, reducing uncertainty and investor fatigue, policies should help facilitate understanding a company’s ESG and plan their sustainability transition. Harmonizing regulation with private initiatives and concerns continues to be paramount for mobilizing all corners of the economy to direct finance into sustainable investment, build trust, and reach common goals.