At the last Future Minerals Forum, held in Riyadh in January 2024, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia clearly stated its ambitions: “Saudi Arabia has the vision, the mineral resources, a large market, regional relations and the right geography to become a key player in the minerals value chain1.” Metals are thus at the heart of the post-oil strategy known as “Vision 2030,” designed to prepare for the diversification of the Saudi economy. The goal of a global ecological transition will require energy and, above all, metals to cope with the deployment of digital and low-carbon technologies (batteries, wind power, solar energy, hydrogen, etc.). Fully aware of this, Riyadh intends to implement a multi-pronged strategy to become a key player in its markets. On the one hand, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is proposing a sustained policy to encourage the development of a national mining industry. On the other, it is seeking to stimulate foreign investment in its territory. Finally, it aims to become the regional center for energy and metal trade between the mineral- and metal-rich countries of Central Asia and Africa.

The potential of the Saudi subsoil: a solution for the post-oil era?

At a time when the climate crisis is forcing the decarbonisation of energy systems and a shift away from fossil fuels, Saudi Arabia needs to rethink its economic model, which is largely based on the hydrocarbon sector. Oil alone accounts for 60% of the kingdom’s budget revenues and more than 75% of its exports2. Aware of these challenges, the Gulf’s largest oil-rich monarchy is preparing to diversify its economy with the launch of its “Vision 2030” development plan in 2016. The plan aims to attract foreign investment to the country and support a number of business sectors, including education, tourism and mining3.

After being the world’s leading supplier of oil throughout the 20th century, Saudi Arabia is dreaming of becoming a regional – or even global – leader in the metal industry. The idea is to exploit the mineral potential of its subsoil and develop an efficient industrial base in the mining and metallurgy sectors. In fact, the kingdom’s mineral reserves have recently been re-evaluated upwards (doubling since 2016), at around 2,500 billion dollars by the Saudi Geological Survey (SGS), even though more than half the territory remains unexplored4. The Saudi subsoil is said to be particularly rich in gold, copper, zinc, lead, and nickel, as well as phosphate, rare earths, bauxite, lithium and manganese. All fundamental resources for the low-carbon transition. These resources could put the kingdom in an ideal position to become a metals producer capable of supplying its own industrial sector, and then potentially exporting a portion to world markets.

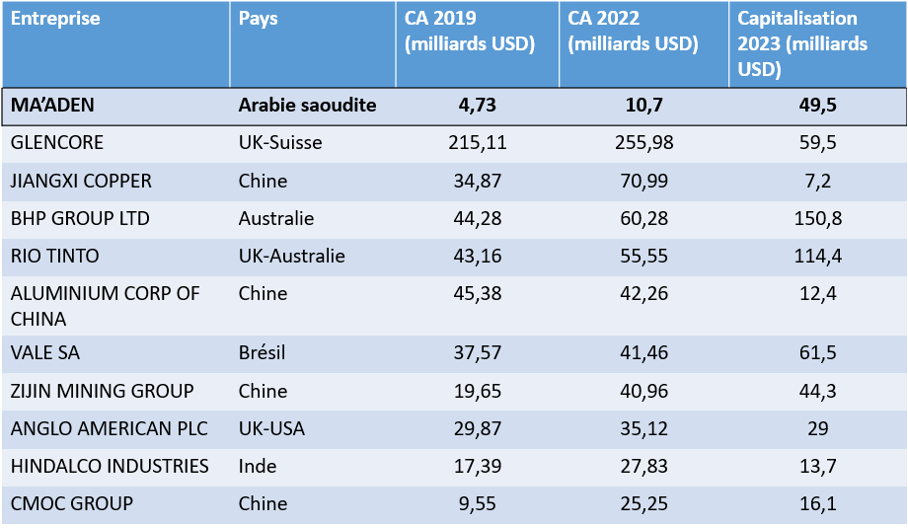

The Saudi government’s national mining project is overseen by the Ministry of Industry and Mineral Resources5 and the SGS, which is responsible for providing geological information on the country’s soil and subsoil. In 2023, Riyadh launched several initiatives to attract foreign investors, including a $182 million programme of incentives for mineral exploration. The kingdom has also developed its regulatory framework to facilitate outside investment and the granting of mining licences, notably through the launch of 33 new exploration licences. The state-owned mining company Ma’aden6, set up in 1997, aims to facilitate the development of the kingdom’s mineral resources. It has also become a key player in Saudi strategy. With sales in excess of $10 billion, annual growth of 25% over the last 3 years7 and a market capitalisation of around $50 billion, it is one of the most dynamic and attractive companies in the sector.

In 2023, Ma’aden teamed up with the Saudi Sovereign Wealth Fund8 (PIF) to create Manara Minerals in response to growth in the country’s mining sector. As soon as it was created, this Saudi joint venture acquired 10% of the Brazilian mining group Vale Base Metals (VBM)9. This partnership is designed to support growth in the energy transition metals market, as VBM is a major producer of copper and nickel.

At the same time, Saudi Arabia is keen to host green and energy transition industries within its borders. In June 2023, for example, it signed a $5.6bn contract with the Chinese electric vehicle manufacturer Human Horizon10. In this way, the kingdom aims to position itself in the various segments of the value chain, from mining to the production of high value-added, technology-intensive products. The aim of the partnership is to produce around 125,000 electric vehicles by 2026, using batteries manufactured in Saudi Arabia and made from Saudi metals.

The development of Saudi Arabia’s mineral potential appears to be one of the pillars of the country’s economic diversification strategy. Does this mean that the kingdom is moving from an oil economy to a commodity economy? The answer is a priori no: Saudi Arabia intends to combine its mineral potential with its economic ambitions by becoming a global energy and metal hub.

Energy and metal hub: the kingdom’s ambitions for the “Super Region”

Through its domestic and foreign investment projects, Riyadh is seeking to occupy a place in the market for the raw materials needed for the energy transition. And this position could be facilitated by its central geographical location between the main African metal producers and Asian countries. The city would become a major commercial hub. Saudi Arabia’s strategy is multi-faceted, since in addition to the proliferation of trade agreements with Egypt11, Turkey12 and Mauritania to develop iron ore mines13, it is aiming to create a trading platform for mineral materials and a regional metals exchange(Saudi Metal and Mining Exchange) capable of rivalling those of London(London Metal Exchange) or Shanghai(Shanghai Metal Exchange). By organising the Future Minerals Forum14 in a mining and metallurgy sector where international governance is sorely lacking, it also hopes to lay the foundations for regional and even international cooperation on these issues. The aim of all these initiatives is to strengthen Saudi Arabia’s economic, financial, institutional and diplomatic foothold, and to position Riyadh as a future anchor in the global metals market.

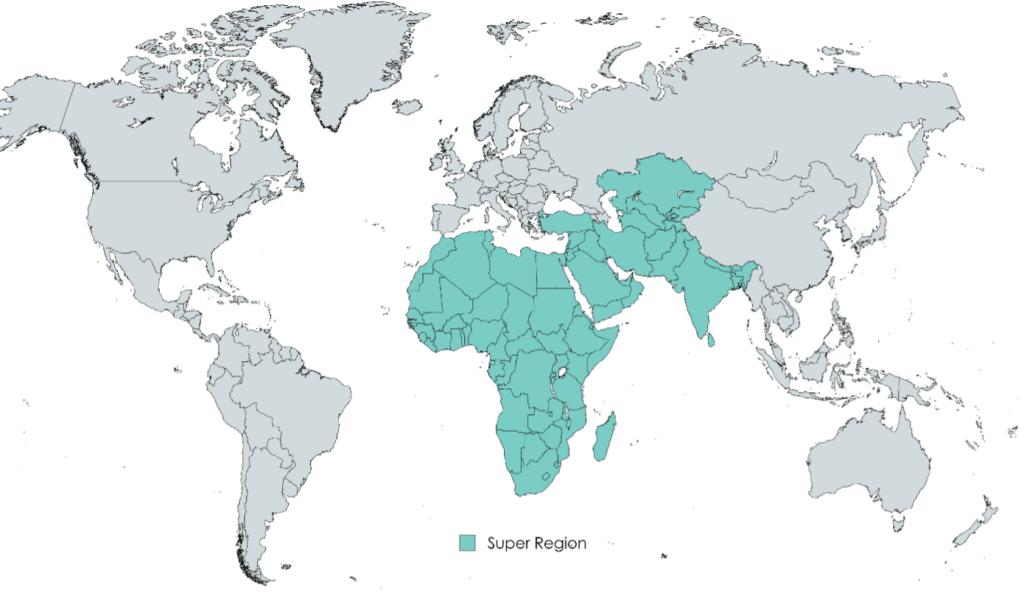

Its position as a commercial hub would enable it to establish itself as a key element of the new “Super Region,” a concept presented by the Saudi capital in January 2024 at the Future Minerals Forum.

This “mineral super-region” stretches from Africa through the Middle East to Central Asia. It covers 79 countries, 3.5 billion inhabitants, 48% of the population and 12% of the world’s GDP15. Despite abundant mineral resources, these countries suffer from a lack of infrastructure, structured financing and skilled labour. Saudi Arabia’s drive for regional integration seeks to fill these gaps. Creating a synergy between the various countries is intended to trigger an economic take-off. It intends to become a major investor in the entire value chain in the region, notably in order to secure its own metal supply chain. This initiative is reminiscent, albeit on a smaller scale, of the Chinese determination seen since 2013 in the construction of the New Silk Roads16.

It is not certain that Saudi Arabia’s regional partners will let it take over the leadership of the group so easily, in terms of both mining and transition technologies. Iran17 and Algeria18 are developing their own mining expansion projects, while Egypt and Turkey have positioned themselves to produce electric vehicles in direct competition with Saudi plans19. So even if Saudi Arabia manages to forge promising regional partnerships, regional competition remains fierce as each country hopes to carve out a place for itself in the global supply chain.

Regional and global competition: the limits of hegemony

The economic repositioning of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia on the mineral commodities market has led to a renewal of traditional alliances and a new strategy on the diplomatic stage: multi-alignment. While the kingdom wishes to maintain certain historic ties, it is also forging new partnerships by joining the BRICS+, in order to consolidate its regional dominance and global standing, while refusing to be part of a single bloc.

Firstly, the move away from oil is weakening the historic alliance between the petro-monarchy and the United States. Since 1945, Riyadh has been linked to Washington through the “Quincy Pact,” which guaranteed oil supplies in exchange for unconditional support for the ruling family and a comprehensive security agreement for the kingdom. To renew the parameters of the alliance, the United States and Saudi Arabia began talks in autumn 2023 to secure metal supplies for both countries in Africa20. Saudi Arabia would take control of African mines through massive investment, and would then reserve part of the production for American companies. For the Saudis, this would be a way of renewing their alliance in a post-oil world, while the Americans would gain access to Africa’s mineral resources. If this partnership goes ahead, Saudi Arabia would become the United States’ link to Africa in terms of mineral supplies, and would enable the Americans to re-enter the race for critical metals, which is currently dominated by China. The Lobito corridor, a railway line linking Tanzania to Angola, could also complement this strategy21. On the Saudi side, the challenge is also to rekindle relations that had become strained with the Biden administration, and to renew a partnership that is essential to the continued existence of the royal family.

In the East, the monarchy is also strengthening its ties with China. In addition to the partnership for the manufacture of electric vehicles, Saudi Arabia has signed a contract with the Chinese Geological Survey, commissioning it to carry out geological surveys over more than 50% of the country22. Saudi Arabia’s ambitions for the “Super Region” do not, however, appear to be competing with the New Silk Roads project being promoted by the Chinese government. The secondary aim of this project was to meet the need to diversify and secure China’s energy supplies. Instead, Chinese and Saudi interests seem to be aligned, in that Saudi Arabia could benefit from the maritime and land infrastructures developed by China in its own mineral materials market project, without challenging the Asian giant’s leadership in this market. Although the two projects – the New Silk Roads and the Super Region – appear at first sight to be in competition, they are in fact complementary, as demonstrated by the project to build a commercial port at Jazan in Saudi Arabia, won by a Chinese firm23. The monarchy also maintains that it does not want to enter into competition with China, but rather to work closely with it, as shown by its decision in 2023 to join the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, an economic bloc led by China.

The Sino-Saudi partnership should above all enable Saudi Arabia to assert itself in its rivalry with its neighbour, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), with which it is in competition on several fronts. In particular, the UAE hopes to sign a free trade agreement with Australia to invest in the latter’s minerals sector24. Generally speaking, the two countries are racing to become the base for investors and businesses in the Middle East, by offering a stable economic and political framework. Secondly, as their economies diversify, the two Gulf countries are competing on the tourism front, but above all in the field of transitional innovations, where the Emirates stand out for their technological lead. So, the Saudi monarchy’s mining project would enhance its attractiveness to its neighbour, strengthening its position as leader in the region.