Responsible investment or greenwashing: how to tell the difference?

- Socially responsible investment (SRI) evaluates investments according to non-financial ESG criteria (environment, social, governance).

- Impact investing adopts active strategies seeking a strong extra-financial return based on three principles: intentionality, additionality and impact measurement.

- However, SRI and conventional portfolios tend to be very similar, and the practical impacts of SRI appear to be very limited.

- Researchers show that SRI investors appropriate the vocabulary of impact assessment without adopting its practices, which is akin to greenwashing.

- To be truly impactful, SRI investors must overcome many challenges and go beyond the integration of ESG criteria.

Socially responsible investment (SRI), which was still relatively unknown until the early 2000s, consists of taking non-financial criteria, such as environmental, social and governance (ESG), into account in the investment evaluation process.

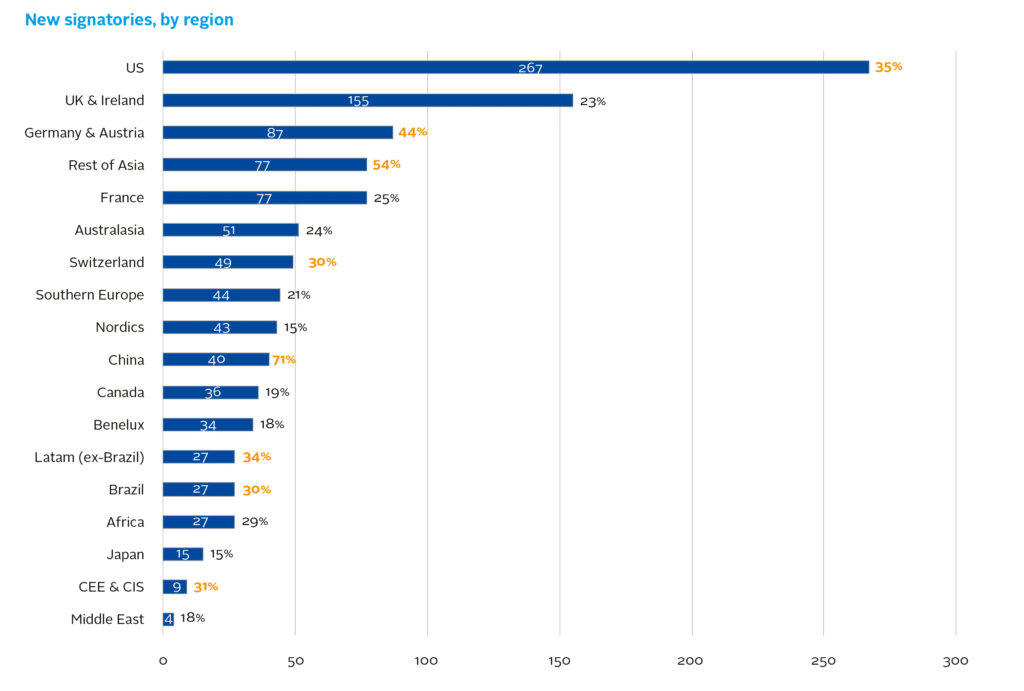

In 2021, 96% of the 250 largest multinational companies on the Fortune500 list (up from 64% in 2005) have disclosed their ESG policy. Similarly, nearly 4,400 investors and 50 service providers, representing more than $120 trillion in assets, have signed a commitment to integrate ESG information into their investment decisions12.

But when it comes to defining ESG standards, differences of opinion abound, and criticism is rife. Elon Musk, for example, called ESG “a scam” and denounced “fake social justice warriors” after Tesla was removed from the S&P 500 ESG index – for reasons related to discrimination and working conditions – while ExxonMobil remained in the index4. Beyond the controversy, a fundamental question about SRI and its true impact on society is emerging.

The Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI)5 were established by the world’s leading investors with the support of the United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP-FI) and the United Nations Global Compact in 2007. PRI signatories commit to the following principles

- Consider ESG issues in investment analysis and decision-making processes.

- Consider ESG issues in shareholder policies and practices.

- Require investees to disclose appropriate information on ESG issues.

- Promote acceptance and implementation of the Principles among asset management stakeholders.

- Work together to increase effectiveness in implementing the Principles.

- Report individually on its activities and progress in implementing the Principles.

Origins and strategies of ‘ethical’ funds

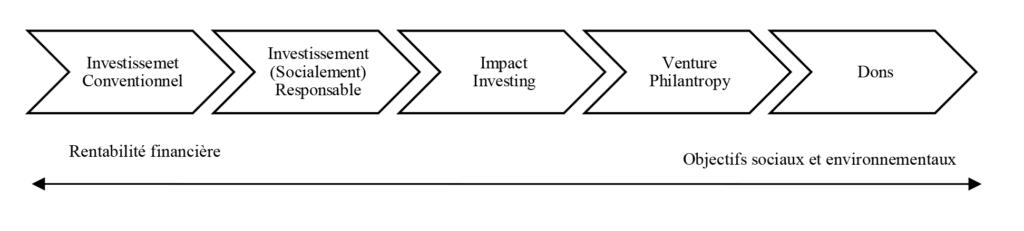

There is nothing ethically wrong with running a business to make a profit while ensuring that production is socially responsible. But impact investing is about more than just ESG-based risk mitigation. It is about supporting companies that are committed to proactively making a difference, and thus demonstrating that you have indeed been able to make a difference on a number of levels.

Historically, the first “ethical” funds were born in the United States. Based on the exclusion of companies linked to the alcohol, tobacco, arms, pornography or gambling sectors, the aim was to meet the requirements of certain investors, including religious organisations. Positive approach funds appeared in the 1970s in the United States and in the 1990s in Europe: these sustainability funds consider extra-financial criteria to promote long-term performance and sustainable growth. More recently, it is notably the Paris climate agreement signed in 2015, the resulting regulations and the awareness of climate risk by major financial players that are contributing to the development of SRI6.

SRI strategies vary considerably: normative or sectoral exclusions (companies engaged in activities that contradict norms or in activities deemed harmful), the so-called “best-in-class” approach (investment in the best-performing companies in a given sector), “best-in-universe” (investment in the best-performing companies regardless of sector), “best-effort” (best improvement in ESG practices), and thematic (e.g. “renewable energies”).

Impact investment is defined by active strategies seeking a strong extra-financial return based on three key principles: intentionality, i.e. the investor’s intentional desire to generate a positive social or environmental impact, additionality (the investor’s specific contribution, financial or otherwise, enabling the company to increase its positive impact), and impact measurement, i.e. the evaluation of the positive and negative externalities of the invested structure8.

SRIs: greenwashing alert?

Until a few years ago, impact investment funds would have been the only investors to carry out an impact analysis: this is no longer the case, as socially responsible investors (SRIs) now aim to demonstrate their concrete impact.

However, the two types of investors (SRI vs. impact) have fundamentally different levels of commitment and different methods of assessment. SRI investors typically invest in listed multinational companies and focus their non-financial efforts on the process of selecting issuers, rather than on the results achieved through their investments. For example, while an impact investment fund will aim to demonstrate the carbon reduction achieved through the financing of wind turbines, an SRI fund will calculate the carbon ‘score’ of the companies in its portfolio.

Finally, SRI and conventional portfolios tend to be very similar, and the practical impacts of SRI seem very limited to a growing number of researchers. It remains difficult to imagine how an investor holding a tiny percentage of a large company’s shares could prove that their investment makes a difference – however well-intentioned. Using traditional impact terminology superficially is therefore far from helpful to the SRI community and may even be akin to greenwashing9.

In a recent study on the confusion between impact and SRI, we show that although SRI investors are appropriating the vocabulary of impact assessment, they are not adopting its practices. However, given the market power of SRI compared to impact investing (about 40 times larger), the appropriation of impact analysis by SRI funds is not without consequences: the diffusion of impact measures in the SRI industry can either support the development of impact investing or threaten its meaning and legitimacy by confusing the two practices.

Similarly, while the SRI industry is genuinely aiming to combat greenwashing, the motivations of investment managers vary, with different levels of commitment to the societal dimension of impact. SRI investors therefore face many challenges in moving beyond ESG integration to true impact. ESG integration seeks to measure the impact of various factors on a company’s financial flows: the materiality of a factor is therefore translated into a variation in the company’s turnover, expenses, or investments. In contrast, impact investing, and more generally impact measurement, seeks to measure the impact of the company’s activities on ESG issues, independently of the financial materiality for the company.