Cheating or chatting : is ChatGPT a threat to education ?

- ChatGPT is a chatbot, i.e. a computer program designed to simulate a conversation with a human, which produces convincing and natural texts.

- Educators are therefore concerned about the risks of using chatbots by students, who may ask ChatGPT to write their essays, for example.

- Tools exist to identify whether a text has been written by a chatbot or not, but it is currently impossible to be 100% sure.

- To identify whether a text has been generated by an AI, it is possible to track down strange wording, unnatural syntax, or instances of plagiarism.

- With the right guidance, chatbots can nevertheless become powerful allies for teaching and studying, but also for the professional world.

Commonly used in customer service and marketing, as well as for gaming and education, chatbots have been around for decades12. The first ever chatbot, ELIZA, developed in the 1960’s at MIT’s Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, was designed to simulate a psychotherapist, using natural language processing to respond to user input. Sixty years on,chatbots are now becoming increasingly sophisticated, using AI to understand user input thus providing more natural and intelligent conversations. As technology continues to progress, chatbots are likely to become even more advanced, allowing for even more natural and personalised conversations being used in a variety of industries, from healthcare to finance3.

ChatGPT, released to the public on November 30th 2022, is a chatbot – a computer program designed to simulate conversation with a human, developed by the San Francisco-based company OpenAI. As its name suggests, it relies on GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer), which is a type of artificial intelligence (AI) model trained on a large amount of text data, used to generate new text in response to users’ prompts. ChatGPT has become popular because of its ability to generate convincing and engaging text upon natural language queries, which has made it a useful and user-friendly tool for tasks like content creation, automated customer support, and natural language processing4. As such, educators are questioning whether the use of chatbots by students is a risk. Moreover, just a few days ago OpenAi released GPT‑4, the successor to ChatGPT. It remains to be seen how much more advanced this new version is than the previous one.

Could students use chatbots in a malicious way ?

While cheating is an age-old problem in education5, AI-based chatbots represent a new route for those willing to cheat by asking questions about assignments or tests. For example, instead of using the reading material provided by the professor, a student might use a chatbot to ask for help with a math problem or get the answer to a multiple-choice question. Note that this is similar to typing a question in a search engine like Google or Bing (which may soon embark ChatGPT6). Whether this rather mundane action is considered cheating is up to the teacher.

While cheating is an age-old problem in education, AI-based chatbots represent a new route for those willing to cheat.

Furthermore, some chatbots are even specialised in solving certain types of problems. DeepL Translate, for instance, is an online AI-based language translation service, which allows users to translate text, websites, and documents into different languages with high accuracy and speed. Other chatbots specialise in writing computer code, including Codebots and Autocode. While these chatbots are initially designed to assist well intentioned users in solving tedious or repetitive tasks, they have the potential to be diverted from their initial purpose by students willing to cheat.

Besides answering short questions, pre-trained AI can be used to generate essays with a semblance of erudition. Paraphrasing tools such as Quillbot, Paperpal, or WordAI, have already been available for several years and can convincingly change a poorly written manuscript into a decent academic paper, or indeed change an original text to escape plagiarism detection. However, more concerning is the ability of some chatbots to generate lengthy, human-looking essays in seconds, in response to a short prompt.

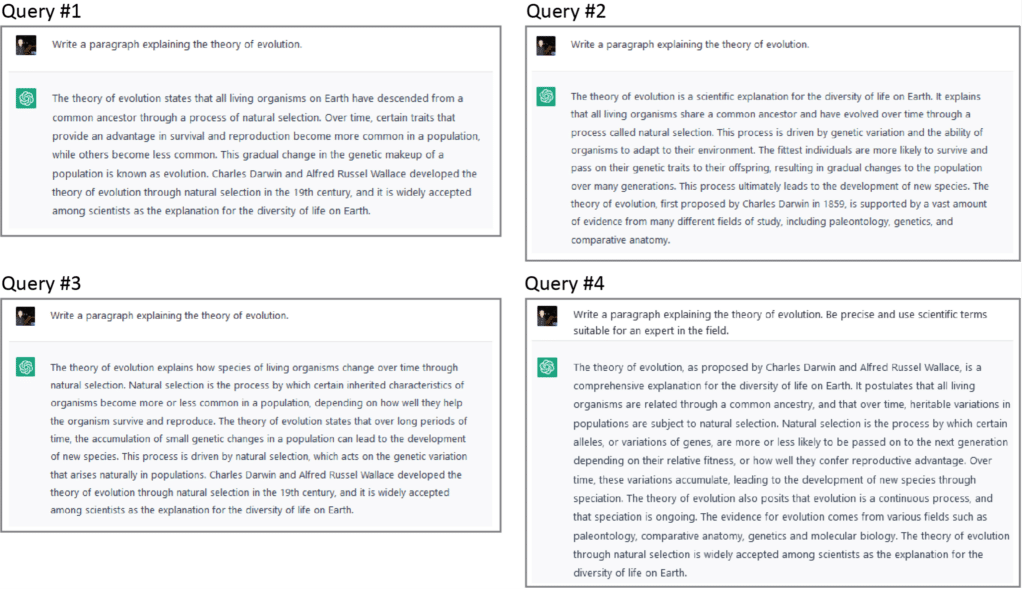

In ChatGPT, students can very simply adjust various parameters, such as the length of the bot’s response, the level of randomness added to the essay, or the AI model variant used by the chatbot. The essay thus generated can then be used as is, or as a starting point that the student can then further edit. With this approach, students can easily generate a solid essay in a matter of minutes. By providing a chatbot with the same prompt multiple times, the software will generate multiple versions of the same essay (see Figure 1). This allows students to select the version which best suits their needs, or even copy and paste sections from different versions to create a unique essay. It is currently impossible to verify with 100% accuracy that the essay was entirely written by a chatbot when this method is applied.

What are the concerns ?

Chatbots make it easy for students to plagiarise without even realising it as they might take the answer generated by a chatbot and submit it as their own work without citing the bot’s sources. This type of plagiarism is especially difficult to detect because many chatbots add randomness to their models. Also, while the chatbot may create novel sentences or paragraphs, it can still provide users with ideas and phrases that are close to their original corpus. It is therefore crucial that users take steps to ensure that they are not plagiarising when using a chatbot. In the future, given some chatbots specialise in finding references7, soon we may see text-writing chatbots using referencing chatbots to source their essay !

Unlike humans, chatbots are limited in their ability to understand the context of a conversation, so they can provide incorrect answers to questions or give misleading information. Also, chatbots may show a wide range of biases. For example, a chatbot might use language in a way that reinforces stereotypes or gender roles, or it may provide incorrect information about stigmatised topics or those which are controversial8910. Microsoft’s Tay chatbot, released in 2016 by Microsoft, was an artificial intelligence project created to interact with people on Twitter. It was designed to learn from conversations with real people and become smarter over time. A few weeks after its release, Tay was taken offline after it began making controversial and offensive statements11.

A particularly distressing concern lies in the possibility that the use of chatbots could lead to a lack of critical thinking skills. As chatbots become more advanced, they may be able to provide students with the answers to their questions without requiring them to think for themselves. This could lead to students becoming passive learners, which would be a detriment to their educational development but could also lead to a decrease in creativity.

Should educators be concerned ?

Chatbots may seem new and exciting, but the technology itself has been around for decades. Chances are that you read AI-generated text on a regular basis without knowing it. News agencies such as Associated Press or the Washington Post, for instance, use chatbots to generate short news articles. While Associated Press turned to a commercially-available solution, Wordsmith, in 201412, the Washington Post has been using its own in-house chatbot, Heliograf, since at least 201713.

The quality of the answers provided by chatbots has substantially increased in the past few years, and AI- generated texts, even in academic settings, are now difficult to differentiate from human written texts14. Indeed, although frowned upon by the scientific community, ChatGPT has been (albeit provocatively) cited as full-fledged authors in some scientific papers15.

News agencies use chatbots to generate short news articles.

Also, while chatbots can (and will1617) be used to cheat, they are just one more tool on the student’s belt. Even without considering the recently gained popularity of ChatGPT, there are several ways students can cheat on their homework, such as copying answers from classmates, using online resources to look up and plagiarising answers, or even hiring someone to do the work for them. In other words : where there is a will to cheat, there is a way.

How can educators act ?

One of the very first steps educators may take against the malicious use of chatbots is to adopt new regulations, whether as a course policy or, even better, at school level18. Updating the standards of conduct would certainly increase students’ and educators’ awareness towards the issue. It may also discourage many students from trying to cheat, in fear of the consequences. However, it would hardly solve the problem in its entirety.

How about changing the way we test students ? One could imagine new, creative types of assignments that may not be easily solved by chatbots. While tempting, this solution bears two issues. On one hand, AI-based technologies, especially chatbots, are a flourishing field. Therefore, a teacher’s efforts to adapt their assignments may very well be ruined at the next chatbot’s software update. On the other hand, forms of questioning that would be considered “chatbot friendly”, such as written essays and quizzes, are invaluable tools for educators to test skills like comprehension, analysis, or synthesis19. New, innovative questioning strategies are always great, but they should not be the only solution.

Another solution yet to be explored is statistical watermarking20. Statistical watermarking is a type of digital watermarking technique used to embed a hidden message or data within a digital signal. In the case of chatbots, the watermark would be a set of non-random probabilities to pick certain words or phrases, designed to be undetectable to the human eye, yet still recognisable by computers. Statistical watermarking could be used to detect chatbot-generated text.

Statistical watermarking is a type of digital watermarking technique used to embed a hidden message or data within a digital signal.

However, this approach has various drawbacks that severely limit its usage in the classroom. For instance, tech companies may be reluctant to implement statistical watermarking, because of the reputational and legal risks if their chatbot was associated with reprehensible actions such as terrorism or cyber bullying. In addition, statistical watermarking works only if the cheating student copy-pastes a large portion of text. If they edit the chatbot generated essay, or if the text is too short to run a statistical analysis, then watermarking is useless.

How to detect AI-generated text ?

One way to detect AI-generated text is to look for unnatural or awkward phrasing and syntax. AI algorithms are generally limited in their ability to naturally express ideas, so their generated text may have sentences that are overly long or too short. Additionally, chatbots may lack natural flow of ideas, as well as use words or phrases in inappropriate contexts. In other words, their generated content may lack the depth and nuance of human-generated text21. This is especially true for long essays. Another concern we raised earlier regarding chatbots was the risk of plagiarism. As such, a simple way to detect AI-generated text is to look for the presence of such plagiarism22. Plagiarism-detecting engines are readily available.

In addition, people can detect AI-generated text by looking for the presence of a “statistical signature”. On a basic level, chatbots are all designed to perform one task : they predict the words or phrases that are the most likely to follow a user’s given prompt. Therefore, at each position within the text, the words or phrases picked by the chatbot are very likely to be there. This is different from humans, which write answers and essays based on their cognitive abilities rather than probability charts, and hence may create uncommon word associations that would still make sense. Put simply, a human’s answer to a given question should be less predictable, or more creative, than a chatbot’s.

This difference in their statistical signature may be used to detect whether a sequence of words is more predictable (a statistical signature of chatbots) or creative (hence likely human). Some programs already exist, such as Giant Language model Test Room (GLTR), developed jointly by MIT and Harvard University using the previous version of openAI’s language model, GPT‑2. We tested GLTR with short essays either written by some of our own students or generated by ChatGPT. We are happy to report that our students’ answers were easily distinguishable from the chatbot (see box below)!

Since GLTR, other AI-detecting programs have emerged, such as OpenAI-Detector, a program released shortly after GLTR and based on similar principles, or GPTZero, a commercial venture initially created by a college student in 2023. Soon, we hope to see the emergence of new tools to detect chatbot-generated text, more tailored to the needs of educators, similar to readily-available plagiarism detection engines.

To cheat or to chat ?

To end on a positive note, let’s not forget that most students willingly complete their assignments without cheating. The first preventive action should be to motivate students by explaining why the knowledge and skills taught during the course are important, useful, and interesting23. Calculators did not put math teachers out of a job. Google did not cause schools to shut down. Likewise, we believe that educators will certainly adapt to chatbots which, despite the legitimate concerns they raise, may soon prove invaluable in many ways. With the proper framework and guidance, chatbots can become powerful teaching and studying assistants, as well as invaluable tools for businesses.

As such, educators should take the initiative to familiarise their students with chatbots, help them understand the potential and limits of this technology, and teach them how to use chatbots in an efficient, yet responsible and ethical way.

Statistical signature could be used to detect chatbot-generated essays.

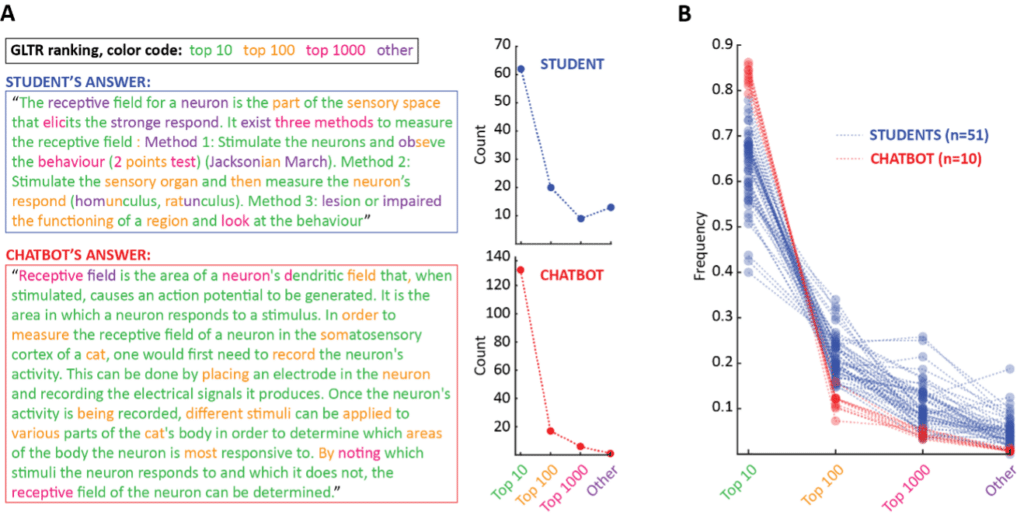

The experiment : As part of a neuroscience course given at Sup’Biotech in Fall 2022, we gathered the written answers of 51 students to the following question : “Briefly define the term « receptive field », then explain how you would measure the receptive field of a neuron in the somatosensory cortex of a cat.” The question was part of a take-home, open-book, timed quiz to be taken on the course website. In parallel, we asked ChatGPT to answer the same question 10 times, to obtain 10 different chatbot answers. We used GLTR to compare the statistical signature of the students’ and chatbot’s answers.

How GLTR works : For each position in the text, GLTR looks at what a chatbot (specifically : GPT‑2, an older version of ChatGPT model) would have picked, before comparing it to the actual word. For example, in the following text : “Biology is great!”, the word “great” is ranked 126th among all possible words that the chatbot could have chosen (the top chatbot choice being “a”). GLTR then generates a histogram of all rankings, which may be used as a simple form of statistical signature : GPT-2- generated texts will be dominated by high rankings, while human prompts will contain a greater proportion of low rankings.

Panel A : Two exemplar answers, one from an actual student, the other by ChatGPT. The texts are colored based on GLTR ranking. The histograms on the right show their statistical signature. Note that the human response contains more low rankings than the chatbot.

Panel B : We overlayed the histograms obtained from all 51 students’ and 10 chatbot’s answers (in blue and red, respectively). Again, we notice a clear difference between the human and ChatGPT texts. In other words, based on the visual inspection of the statistical signatures, we are quite confident that our students did not use ChatGPT to answer the question.