Preserving cultural heritage, raising the profile of art collections and making immersive museum experiences accessible to as many people as possible in a dedicated metaverse… As the winner in 2023 of wave 3 of the PIA4 (Plan d’investissement d’avenir) call for projects ‘Digitisation of heritage and architecture’, the Métavers du patrimoine project is tackling these ambitious objectives. Led by Manzalab, the consortium also includes Ecole Polytechnique, Télécom SudParis, Mus’X and Forum des Images. The idea is to digitise works of art and then insert them into collaborative and interactive virtual worlds. Ultimately, the aim is to offer museums the possibility and the right tools to digitise their artefacts and redefine cultural experiences.

Accessibility, conservation and the reinvention of cultural experiences

Europe, and France in particular, has a rich and well-preserved museum heritage. Digitising works of art ensures their preservation and makes them more accessible. This is what Titus Zaharia and Marius Preda, professor and lecturer respectively at Télécom SudParis, are seeking to achieve under the umbrella of the “Métavers du patrimoine” project. The aim is to create 3D representations of objects so that they can be visualised in a virtual environment called a metaverse. “The idea is to use digitised works of art and virtual worlds to support an experience,” explains Marius Preda.

The fusion of art and technology is opening up new prospects for museums. While some fear a dematerialisation of the artistic experience, according to the experts, it is above all an opportunity to broaden the audience and generate new forms of engagement. Virtual worlds know no spatial boundaries. In the metaverse, for example, an exhibition that is usually restricted by the surface area allocated to it could transcend the physical barriers of the real world. The creation of innovative, immersive experiences could also arouse new interest among visitors. As Marius Preda points out, “I don’t get the impression that the younger generation is keen to visit museums in the traditional way. I see this as an opportunity to reach them, as they are already very used to consuming digital content.” Lastly, the museum metaverse project promotes accessibility. Without the need to travel, this new way of experiencing exhibitions could become a major educational and cultural lever.

Digitising with photogrammetry

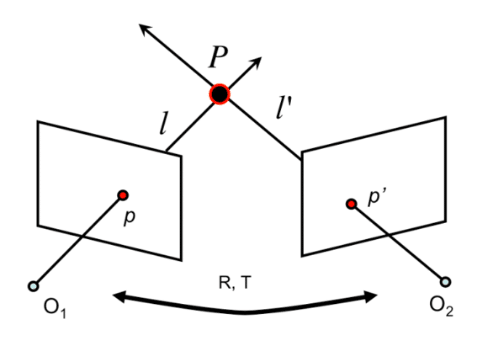

Photogrammetry is the cornerstone of this process. Synonymous with measurement by photography, this technique is based on a very old principle: the calculation of distances by triangulation. This method, which enables large distances to be measured accurately, was used to map territories in the 17th century1. By imagining a triangle on a piece of land, we can determine the length of the other two sides from the angles. Once the length of the first triangle is known, another triangle with a side in common with the first can be calculated. To digitise objects, scientists use a similar process: several cameras take images of the object from different angles. Using the 2D images of the work, the scientists are able to calculate positions in three dimensions. They find common points between the images captured and calculate the 3D position of each pixel. They then put these measurements together to reconstruct the three-dimensional object.

Capturing the complexity of works of art while respecting their artistic essence is a challenge. Firstly, this technique can only represent the surface of the object, not what it contains. What’s more, the diversity of art forms requires constant adaptation, with each creation requiring a specific approach. The material of the work is one of the main obstacles. “If it is capable of reflecting light, then it can be digitised”, says Marius Preda. This being the case, translucent or transparent objects cannot be digitised using this technique. Another factor is the size of the object. The smaller the object, the easier it is to capture. When the object is too large, scientists use drones to capture the images. This method is used, for example, to digitise architectural works.

The question of use remains an issue

The digitisation of works of art opens up new artistic possibilities. “Once digitised, there are an infinite number of ways of representing the object. You can play with multiple parameters such as transparency, colour or even shape,” explains the lecturer. But this vast field of possibilities raises ethical questions, particularly when it comes to the modification or representation of ancient cultural objects that could offend certain communities.

“You have to bear in mind that having works digitised in 3D is not enough to make a metaverse, there are other aspects that need to be taken into account,” insists Titus Zaharia. In the end, although digitising works of art involves a number of highly technical processes, there are no major technological barriers to gamification, capturing, making available and creating experiences. The current challenge is above all to discover the right uses. Titus Zaharia asks, “At what point does a user think they are visiting a virtual reality museum?”

According to the researchers, these virtual museums will be collective experiences. Marius Preda adds: “I don’t believe in experiencing things alone at home. I believe more in online group visits, like playing video games.” To achieve this, technologies need to be democratised and developed to ensure that they are user-friendly. For example, current virtual reality headsets are heavy, uncomfortable and expensive. Without “good” devices for accessing metavers, the user experience will be compromised.

So, while technology opens new doors, innovation is nothing without ‘uses’. This French project is being run with and for museums. Many museums and cultural institutions are already represented, either as partners in the project, such as Mus’X and the Forum des Images, or as members of the steering committee, such as the Château de Versailles, the Musée du Quai Branly, the Musée des armées, the Bibliothèque nationale de France, the Cité des sciences et de l’industrie, the Musée d’archéologie nationale, the Musée de la Marine, the Palais des beaux-arts de Lille and the Château de Chambord. Ultimately, the aim is to enable museum staff to carry out 3D recording independently, using a platform that the researchers are developing. This platform will have to understand the needs of the institutions and adapt to their business models. If these cultural metaverse projects are to be democratised, individual museums will need to be able to create their own content, with a high degree of customisation and scripting of the user experience.