Society is becoming increasingly divided, and we are continuing to see the emergence of extremist views around the world, be it with regards to topics like politics, religion, or climate change. While there has been a great deal of research into how this phenomenon, which is known as ‘polarisation’, has evolved less attention has been paid to understanding how social interactions can lead to the opposite effect – “depolarisation” –, which occurs when individuals begin to modify their opinions so that they are less extreme.

To address this question, Jaume Ojer, Michele Starnini and Romualdo Pastor-Satorras, from the Departament de Física, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya and the CENTAI Institute in Turin, have proposed a new “social compass” model to study how opinion varies between groups with extremist positions and how these opinions might be depolarised1. Their theoretical framework has been validated by extensive numerical simulations and tested using data from opinion polls collected by the American National Election Studies.

Several subjects for one opinion

“Polarisation may contribute to widening the political divide in our society, hampering the collective resolution of important societal challenges,” say the researchers. “It could even encourage the spread of misinformation and conspiracy theories. Our depolarisation framework could provide solutions to these societal ills.”

Models describing polarisation are based on mechanisms as diverse as homophily, bounded confidence or opinion rejection. Until now, the depolarisation process in a population has generally been modelled for the simple case of an individual’s opinion on a single subject. In reality, however, an individual generally has opinions on several subjects at any given time. A multidimensional modelling framework is therefore needed to better describe how opinions evolve.

When multiple subjects are considered, a number of features emerge. The first is alignment, that is, the presence of a correlation between opinions with respect to different subjects. For example, people with strong religious convictions are more likely to oppose abortion legislation. The problem with current multidimensional models is that they neglect this interdependence between different subjects, which means that they fail to clearly describe opinion polarisation.

The social compass model

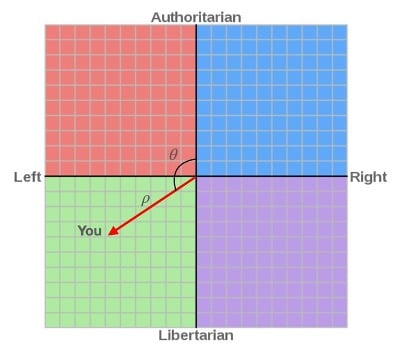

The key idea of the social compass model is to represent opinions in relation to two topics located on opposite sides of a polar plane. The angle of the plane represents an individual’s orientation as regards to the two topics, and its radius expresses the strength of the attitude (or ‘conviction’).

“This polar representation naturally allows us to formulate the key hypothesis of our model, namely that intransigents with extreme opinions (or strong conviction) may be less likely to change their opinion than individuals with weak conviction,” explains Michele Starnini. This hypothesis is intuitive and consistent with observations made in experimental psychology. “Such a polar representation is very common in physics, but not so much in the social sciences.”

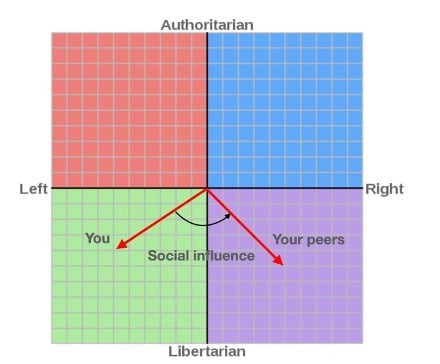

Inspired by the Friedkin-Johnsen model2, the researchers studied how social influence can affect the initial opinions of individuals. They found that their model describes a phase transition from an initial polarised state to a depolarised state as a function of increasing social influence. The nature of this transition depends on the disparity of initial opinions: opinions that diverge strongly at the outset trigger a so-called first-order (or explosive) depolarisation towards consensus, while opinions that are more correlated to begin with lead to a second-order (or continuous) transition.

Interactions and influences

To test their model, the researchers used data on correlated topics – such as abortion and religion – and uncorrelated topics – for example, immigration and military diplomacy in the United States – from the American National Election Studies. They found that communities asked to give their opinion on these subjects underwent a phase transition from polarisation to depolarisation in numerical simulations of the model, with individuals in the community interacting and influencing each other.

They studied the model under “mean field” conditions, meaning that each individual can interact with all the other individuals. “Since opinions are described by angles, it was natural for us to model consensus formation as the alignment of agents’ orientations,” explains Michele Starnini. “This type of phase coupling is inspired by the Kuramoto model and is realistic for small groups. In future work, we will test our model on large interacting groups, such as social networks.”

“Another interesting application that we are looking forward to implementing involves simultaneously measuring the opinions of individuals with respect to multiple topics and their social interactions, to test the model in this more realistic setting.”