How long has INRS been interested in this subject?

In 2012, INRS launched an initial prospective study entitled “Use of physical assistance robots by 2030 in France”. At the time, there were two exoskeletons in France that were being tested in companies. Barely ten years later, there are some forty of them available on the market! They range from posture harnesses that help relieve the back to robotic exoskeletons that compensate for effort. For us, it is exciting that research and interventions in the field are in phase with the emergence of these physical assistance technologies.

Why are companies using exoskeletons?

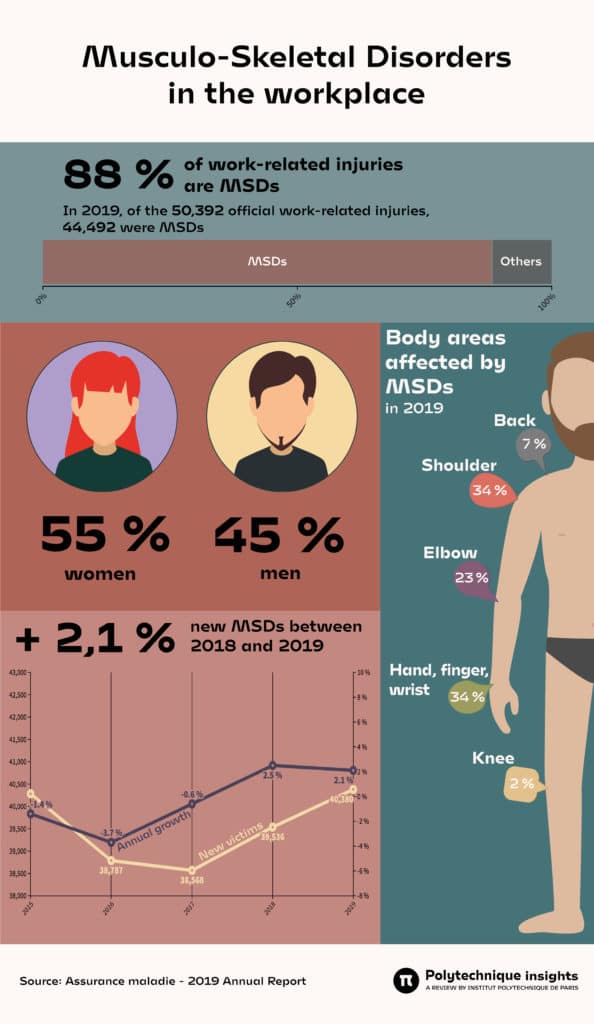

Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) account for 87% of occupational illnesses and back pain accounts for 20% of work-related accidents – a sizeable number! As well as the damage caused to employees, MSDs have a high economic cost for companies and social security (days off work). This is why mechanical devices that help compensate for the physical efforts of operators or assist them in their movements are already employed or being studied in all fields: from the automotive to the nuclear industry, including construction, mass retailing, the health-medical-social sector, etc.

How do you study these devices?

The laboratory studies focus on handling and holding loads to observe the consequences on the activity of the muscles that are assisted as well as those that aren’t, on posture and on motor coordination. For the shoulder, for example, our team has studied the space between bone and between tendon tissue using ultrasound and compared the behaviour of joints with and without exoskeletal assistance. We are also carrying out assistance in conjunction with prevention networks in companies to analyse how exoskeletons are integrated and whether or not they are being accepted by employees. It is important to understand that the difference between this technology and “classic” physical assistance is that it is attached to the person’s body. This assistance, while helping to reduce effort, can, at the same time, be felt by the wearer as a physical and psychological restraint.

Do these devices effectively relieve physical effort?

Exoskeletons can bring significant benefits, but they offer very localised assistance and do not address all the physical constraints to which employees are exposed. Importantly, they can themselves create new biomechanical constraints: impact on the muscular activity of muscles not assisted by the exoskeleton, impact on balance, on motor coordination, suitability for high rates of work and high degrees of movement repetitiveness, transfer of biomechanical demands to other parts of the body, etc. The nature and extent of the benefits or limitations observed depend on the activity performed (the working posture adopted, load handled, work rhythm, etc.), the technical characteristics of the exoskeleton (contact points, weight, stiffness, etc.), and the tasks identified.

So, it’s not that simple for companies to adopt these exoskeletons?

They must think very carefully before choosing equipment and consider the impact it will have on the whole work organisation. We are publishing guides to help them ask the right questions. First, thinking about possibly making use of an exoskeleton must be accompanied by a broader reflection aimed at reducing the constraints linked to physical activity through organisational changes, training, etc. The precise nature of the physical assistance required must then be defined (the body areas to be assisted, postures usually adopted, load weights handled, etc.)

If the exoskeleton solution is chosen, it is then crucial to initiate a test process by addressing precise evaluation criteria: to what extent has the operator taken on the equipment? Is it easy to use? Is it really useful? What are the effects of using the exoskeleton on the environment and the work group? How many people in a team will be equipped with an exoskeleton? How will others view those who wear it? The exoskeleton must be included in workstation analysis risks, as it may, for example, lead to new collision risks for the person wearing the equipment.

Many companies do not realise the extent to which exoskeletons can disrupt an entire working environment.

What are the regulations on the subject?

We must remember that exoskeletons are there to “assist” operators and not to “enhance”. To put it plainly, in the future, operators will not be carrying loads that they were not carrying before, but rather carrying loads that they were already carrying with less risk of impact on their health. In this respect, the standards in force today concerning load and physical stress limits for manual handling tasks must continue to be respected.

Exopush: a textbook case

In 2014, the company Colas1 experimented with its first robotic exoskeleton, “Exopush”, for roadworks where workers had to spread and level asphalt on the road. A kind of robotic rake was developed. It consisted of a harness, a strut that transfers the weight of the load to the ground in order to reduce effort and improve the user’s posture and a telescopic handle that detects the user’s intention and extends his movement. This equipment was little used in the field, however. A multi-disciplinary steering committee bringing together the company’s internal and external prevention players was then set up, with the participation of the INRS. Numerous meetings with the teams were organised, the equipment was adapted, the workers were trained, and a dedicated deployment manager was appointed in 2019 to generalise the use of almost 90 Exopushes in the different branches of Colas.