The global pandemic has had a significant impact on the aviation industry. To date, IATA estimates that the industry has received ~$110 billion in direct aid, and an additional ~$60 billion in wages, taxes and subsidies. So, does that mean less investment for carbon-efficient tech? A team of researchers from Goldman Sachs recently published a report “The decarbonisation toolkit and what it will mean for airlines.” They conclude that decarbonisation of the sector will remain a focus for airlines and policymakers alike post-covid and assess the potential impact on airline growth and financials.

How has the pandemic impacted the sector?

Venetia Baden-Powell. Covid-19 has resulted in the deepest civil aviation traffic recession in history. We forecasted a ~70% drop in air traffic in Europe in 2020, multiple times worse than in 1991, 2001 or 2009. The knock-on effect for employment in the sector has also been sizeable, with airlines announcing layoffs equal to 10–30% of their workforces. At these traffic levels, airlines burn significant cash flow: across five of the largest airlines in Europe, we forecast ~€14 billion cash burn in 2020. Financial stress has required airlines to raise capital, either government-backed (e.g. Air France, Lufthansa) or via the equity market (e.g. IAG, easyJet, Ryanair). In Europe, direct aid provided or pledged across airlines was ~€30 billion.

How carbon intensive is the sector and is a low-carbon future a realistic prospect for airlines following the pandemic?

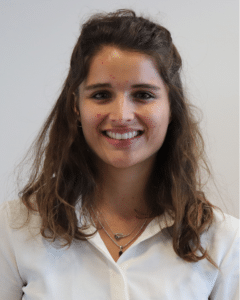

The answer to this is nuanced, which we explore in depth in our report. Pre-pandemic, aviation accounted for 4% of EU greenhouse gas emissions, up from 2% in 1990, driven by significant traffic growth (2x GDP historically). While the increase in emissions has been mitigated by improvements in aircraft efficiency, the sector remains one of the most CO2 intensive and has lagged other industries in reducing its intensity. This explains why policymakers are focused on the sector from a carbon perspective, in particular in the wake of large-scale government financial support for the industry.

That said, following the traffic drop we forecast in 2020 (~70%), aviation’s share of emissions could fall to 1–2%, all else equal. Given we don’t expect a return to 2019 traffic levels until the mid-2020s, this means policymakers no longer need to curb absolute activity levels for the sector, but rather refocus on incentivising efficiency gains and sustainable growth. Indeed, some announced rescue packages for the sector have “green” conditions, such as Air France. These include the reduction of CO2 emissions/passenger km by 50% by 2030 (vs. 2005 levels), in part to be driven by modal shift to rail on domestic routes and increasing biofuel use.

A similar response can be seen in Austria following Austrian Airlines’ support package, where the government plans to increase taxes on short-haul flights, introduce a price floor of €40 on any air ticket and invest more in rail. These policies are likely to be complemented by structural shifts in consumer and corporate demand. Overall however, new technologies to drive low or ultra-low carbon aviation won’t be available until post-2030. These include new propulsion technology such as hydrogen and engine hybridisation/electrification.

What impact could the decarbonisation levers available to policymakers & airlines have as the sector recovers?

The main levers being discussed are incremental taxation, rail promotion and fleet renewal. Announced passenger taxes on EU short-haul could increase low cost carrier fares by ~15%, which we estimate could translate into a mid-single digit % hit to demand and therefore emission. These will be implemented alongside greater rail investment. For example, a €40bn “Renaissance of Rail Investment” package is being considered under the EU’s Green Deal. We estimate that up to 15% of EU air traffic networks are at risk from rail substitution.

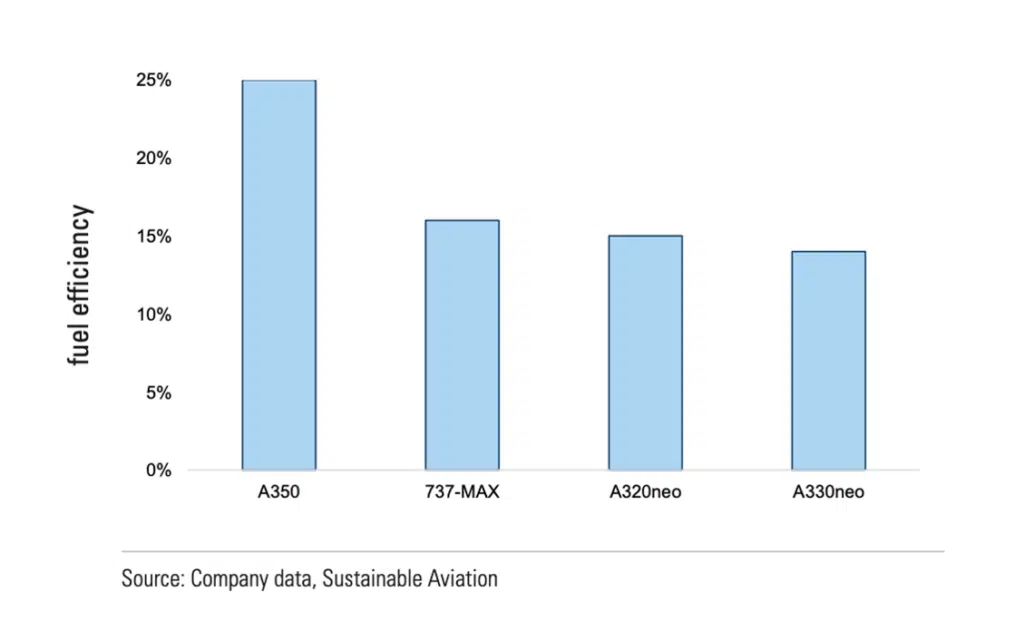

Finally, a more organic way for the sector to reduce its carbon footprint near-term would be through fleet renewal. Full adoption of new generation aircraft could reduce emissions by nearly 20%, all else equal. While covid has lowered the sector’s near-term investment capacity to buy new, efficient planes, we believe medium-term fleet renewal plans are unlikely to change. This reflects the importance of fleet renewal in maintaining an airline’s competitive position, particularly in a subdued demand and fare environment. In fact, covid has generally served as a catalyst to retire inefficient aircraft with many airlines expecting to run smaller, more efficient fleets medium-term.