Where new geographical regions are ready for wine production ?

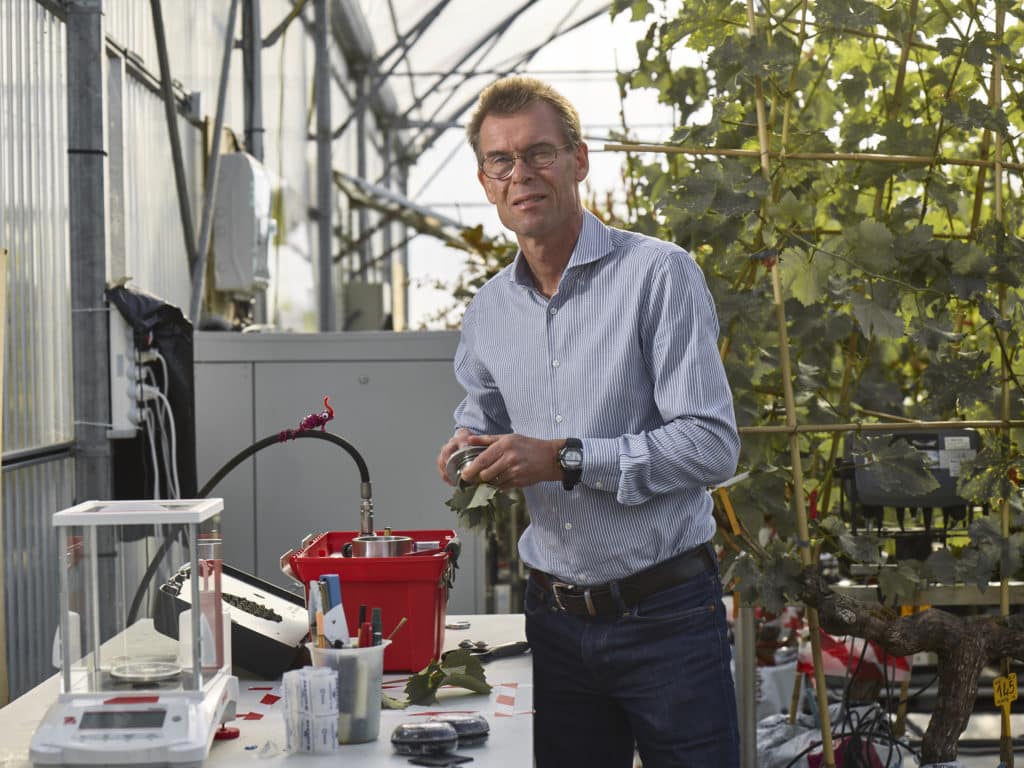

Cornelis van Leeuwen. The arrival of vineyards in England, Belgium and The Netherlands is a logical consequence of climate change. England, for example, is becoming an established wine-producing country. It is now capable of producing high-quality wines costing €25–30 per bottle on the domestic market.

Today, these relatively new “terroirs” are well suited for production of white and sparkling wines because their climate requirements are lower than those of red wines. They require sustained acidity and grapes with low sugar levels, so can therefore be produced in regions with relatively cool temperatures. We have observed this in the French regions of Alsace and Champagne, or in new wine-making countries such as New-Zealand and Tasmania, which all benefit from the same characteristics.

How does global warming impact the development of these new terroirs ?

Vines respond to temperature and sunlight, as well as water availability and soil mineral concentrations. These resources are different in each location. Abundance varies from place to place, influencing vine physiology, which in turn affects yield, taste, ripening, and grape composition. As such, climate plays an important part in each of these aspects. Normally, natural conditions vary only slightly each year – giving rise to the notion of “vintage”. But in the face of climate change, this stable element has become a variable. In the wine-making community the first scientific articles recording the effects of global warming were published 20 years ago. Warming accelerated in the 1980s, yet people only became aware of this issue in the 2000s.

In what way are the consequences of global warming different from one place to another ?

Vineyards are becoming hotter everywhere in the world, and water conditions are changing too. North of the 45th parallel (including Bordeaux and Bologne), rainfall is tending to increase year on year. Whereas we observe a decrease in the South. Evidently, the impact of global warming is different depending on the climate of the region. Northern regions have seen problems with the insufficient maturity of grapes (aroma, excessive acidity, deficit in sugar) which can be resolved. However, countries like Spain or Italy are more impacted in terms of quality and yield. It will be more difficult for these regions to adapt. Between the 35th parallel (Tanger, Tunis) and the 50th parallel (Charleroi, Prague), limiting factors to produce good wine are not the same.

What is the situation in the South ?

We observe a water shortage. But the problem with drought is primarily a yield problem. When the vineyard is well managed and planted with drought-tolerant grape varieties and rootstocks, it is possible to produce high-quality wines with only 300 or 400mm rainfall per year. However, to ensure financial viability, you must produce fine wine sold at a good price, with sufficient yields as well.

There seems to be confusion as to the effects of temperature and water shortage. You cannot compensate excess heat with irrigation ; and besides, vines are very well adapted to drought. Winemakers in Mendoza (Argentina) have found an interesting solution to deal with rising temperatures : they now plant at altitudes as high as 1,400m compared to traditional vineyards were located at 800m. But obviously this solution cannot be applied everywhere.

Irrigation of terroirs is therefore a controversial practice ?

Historically, the large majority of vineyards was located in Europe, where there was no irrigation, including in very dry regions such as Andalusia or Sicily. In the new world, irrigation is used for other crops, and so could also be applied to viticulture. Nevertheless, it is more a question of water availability and cultural decisions. Irrigation can increase yields, but it requires 1–4 million litres of water per acre, per year. It is upsetting to see the development of irrigation on a large scale in countries with limited water resources, like Spain. To irrigate, we often draw on groundwater, which is an environmental crime.

UK climate warmer, but less stable

Warmer temperatures in the UK due to climate change offer an environment more adapted to wine production. Viticulture climatologist and CEO of Vinescapes, Alistair Nesbit has been involved in the UK wine sector for around 20 years. He says that “the sector has grown 200% over the last few years in terms of scale and volume. People are growing wine in areas that were too cold only 30–40 years ago. The UK now has around 3,000 hectares (ha) of vines with over 700 vineyards producing wine.” Still comparatively low when compared to other countries more traditionally known for their wine production ; ~800,000 ha in France, ~1 million ha in Spain or 650,000 ha in Italy 1.

“Whilst other countries and regions are struggling with heat and drought, the UK wine sector is benefiting from the warmer climate.” In particular a stable 13°C average temperature 2. “But not everything is as ideal as it may seem,” he argues. After all, grapes need more than just warm weather to grow. British vineyards are particularly subject to risk of frost and unstable rainfall, with much variability year on year ; conditions that grapes don’t bode well in.

As such, even though the British wine sector has seen much investment, yields remain low. In a study from 2018, Alistair Nesbit and his colleagues pointed out the fact that low yields were due to unsuitable locations of vineyards 3. Their report identifies suitable landmass in the UK of 33,700ha – equivalent to the French Champagne region – with an average temperature of 13.9°C during growing season, that could successfully be converted to vineyards in the UK.

Still, there is more understanding needed if the sector is to be successful. A project between climatologists, wine sector specialists and researchers at the Grantham Research Institute and the University of East Anglia, CREWS-UK, aims to look at future climate conditions in the UK and its potential impacts on wine production 4.