Why is it complicated to define food waste?

In France, a distinction is made between waste, unnecessary waste, and losses. We talk about unnecessary waste for products that are discarded (sorting, overproduction…), lost (harvesting, processing, transport…) or not consumed (expired, served but thrown away). It also includes parts that we do not usually consume (melon skin, chicken bones, cherry stems…), whether or not they are recovered. And we generally use the term “losses” to talk about products lost upstream, during production and processing, because this word does not have the same negative connotation as “waste”.

Depending on the region and cultural habits, certain foods (or parts of foods) may or may not be considered edible: leek greens, citrus peels, fish heads are not cooked everywhere in the world. Moreover, in some countries, food that is reused for animal feed or energy production is not considered as “wasted”. This leads to differences in definitions, and therefore actions, from one country to another.

What are the waste figures?

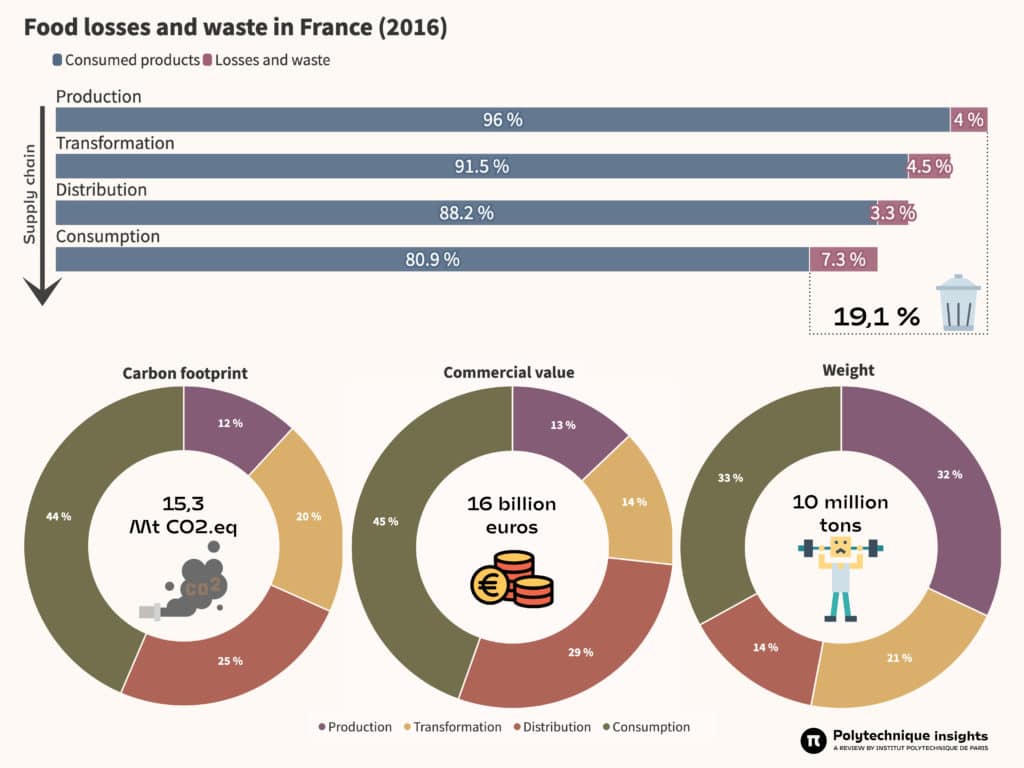

In 2011, the FAO presented the first global estimate: about one third of the edible parts of food produced for human consumption is lost or wasted, which corresponds to about 1.3 billion tonnes of food per year. The waste is fairly well distributed in all countries and between the different levels of the food chain: 1/3 upstream (production), 1/3 downstream (at consumer level), 1/3 in between (distribution and processing).

For France, Ademe published the most comprehensive study in 2016 by cross-referencing different data and conducting over 500 qualitative interviews1. In 2016, the total amount of food loss and waste was 10 million tonnes. The waste generated in the home is equivalent to 30 kg per person per year, including 7 kg of uneaten food waste that is still packaged, and represents approximately €108 per year per person (€240 if we consider all the losses and waste generated throughout the chain). It should be noted that four times more is wasted in collective and commercial catering than in the home (130 g/meal compared to 32 g in households).

How did the battle against food waste begin?

The British started as early as 2005, with the first studies and various actions put in place, but France was a pioneer in terms of legislation. In the framework of the National Pact to Combat Waste in 2013, it set a target for reducing food losses. Then, in 2016, the Garot law (named after the MP Guillaume Garot) prioritised actions to combat waste, banned the destruction of edible food, and obliged shops over 400m2 to draw up a donation agreement for food that had previously been destroyed.

In 2018, the Egalim 1 law extended the possibility of donations to collective catering and the agri-food industry. Finally, the 2020 Anti-waste for a Circular Economy (AGEC) law extends the Garot law to the wholesale trade and adopts targets for a 50% reduction in loss and waste. By 2030 for producers, the food industry, and consumers, by 2025 for distribution and collective catering. These are very ambitious targets, which aim to set an example at European level.

At the international level, 2015 was a decisive year, with the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The objective is to halve the volume of food waste per capita by 2030, both in distribution and consumption, and to reduce losses throughout the production and supply chains.

In France, has this awareness already led to a reduction in waste?

There are still no reliable indicators to monitor the evolution of waste. Many actors, whether upstream (farmers and breeders) or downstream (notably commercial catering, tradesmen, households), only have a vague idea of what they lose, and often tend to underestimate it. As for manufacturers and distributors, they are often faced with a problem of data confidentiality.

But a European directive makes it compulsory, from 2023 onwards, for each country to publish a global waste figure every four years and a figure per item every year: collective and individual catering, households, etc.

Our objective at Ademe is to set up tools to help actors at each link in the chain to make diagnoses and define their reduction actions. We have already developed such tools, for example for canteens, which help managers to measure waste and then reduce it2, or for food manufacturers3. The important thing is to get the ball rolling, to show the various players that it is possible and profitable since it allows them to save on production costs.

Do you think the 50% reduction target is realistic?

It is very ambitious, because it is often quite simple to reduce losses by 30%, but to reach 50% requires real reflection and changes in behaviour. But people are supported, it is feasible. In 2019, as part of a “zero waste academy” operation, we recruited 243 households who agreed to assess their waste and then follow « anti-waste » gestures. One year after the start of the survey, they weighed the discarded food products again: they had reduced their waste by 59%!

Are the resources devoted to the fight against waste sufficient?

They are decreasing. Although significant resources were put in place in 2016 and 2017, it has been difficult to mobilise them since. It is however essential to have relays in the territories such as the REseaux de Lutte contre le Gaspillage Alimentaire (REGAL) which help to raise awareness among all the actors. It would also be necessary to run a major national information campaign on this issue.

Fortunately, in civil society, companies such as Too Good to Go and Phenix have not waited to act and are effectively shaking up public authorities and consumers alike by inventing original solutions to combat waste.