You led the working group of think tank The Shift Project which published a report in 2018 entitled “For digital sobriety”. What did you find then?

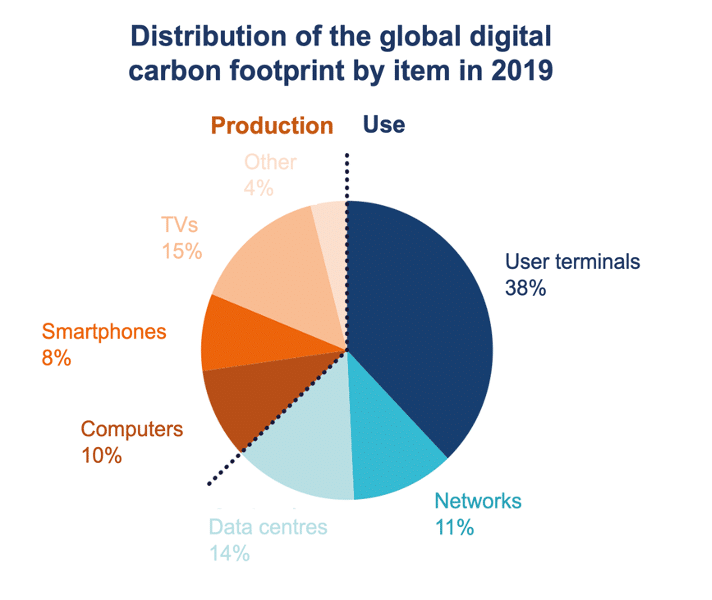

Hugues Ferreboeuf. The aim was to analyse the evolution of the environmental footprint of the digital sector1. We found that 45% of the sector’s energy consumption is due to production of equipment and 55% to its use. We identified two dynamics at work. On the one hand, a technological dynamic was providing significant energy efficiency gains with each new generation of equipment – as such, it was possible to do more with the same energy consumption. On the other hand, however, we observed an explosion in use. We also showed that improvements in energy efficiency ratio of equipment is not enough to compensate for the increase in use. In other words, for digital technology to be energy efficient, to reduce its environmental footprint, we must inevitably look at how to limit the development of certain uses that are not very virtuous in environmental terms, particularly video!

Video now accounts for 65–70% of global data flows and, with more than 300 million tonnes of CO2 emitted per year, it is responsible for 20% of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the IT sector. Above all, less than 10% of the uses are professional, such as videoconferencing or telemedicine. The rest is divided between viewing video in the form of films, porn, music clips, or those little videos that are automatically triggered when you visit a site. These figures led us to publish a specific report in 20193 in which we call for a reduction in the weight and use of leisure video, which requires some form of regulation and therefore societal debate.

How can we limit or curb usage?

It’s complicated! The problem is that uses do not replace each other, they add up. The switch from DVD to streaming, for example, has resulted in an increase in screen time. If emissions are increasing every year, it is because we are consuming more. And if we are consuming more, it is because the business models of the suppliers, their marketing and technological techniques encourage us to consume more. Simple processes such as automatic start-up of the next episode in a series make us stay in front of our screens. This is called ‘addictive design’. Another aspect is that the cost of subscription, Netflix for example, reduces the marginal cost of subscription for the user – that means the more you consume the cheaper it is. But once we are aware of the impacts of our consumption, our inaction becomes reprehensible. It is not just a question of individual responsibility: we need to change our economic model.

Can improvements and advances in technology help to reduce energy consumption?

Yes, but this will not be enough to absorb the increase in usage. Moreover, some technologies are reaching their physical limits. In fact, we are likely to see a slowdown in energy efficiency gains over the next few years. We have used this analysis, which takes into account individual practices and the structuring of supply, in a report published in October 2020, entitled “Deploying digital sobriety”4. The growth of digital uses is a systemic phenomenon in which supply and demand play a role, but also the political and regulatory framework. To solve a systemic problem, we need a systemic solution, we need to act on the different vectors that lead to this “overgrowth”. In this report, we published a sort of methodological reference framework for companies in the broad sense to help them integrate the principles of digital sobriety into everything that makes up their information system. Now that digital technology is everywhere, companies cannot limit themselves to a technological approach to the issue of sobriety. It is becoming a concern for top-level management which must be integrated into a company’s strategy.

In concrete terms, how can we reduce our environmental footprint linked to digital technology?

First, by not changing smartphones so often! In France, people change their device on average every 20 months. What you need to know is that 99% of the carbon footprint of a smartphone is linked to its production and transport to France. Elsewhere in the world, this share is 90% on average. The difference is that electricity is very low carbon in France… Secondly, we must avoid multiplying gadgets, accessories, and additional equipment. The number of connected objects, screens, devices, etc. per person in the United States is expected to rise from 13 today to 35 objects in 2030. And what we see is that the growth is strongest where there is already a plethora of equipment, namely in North America, Western Europe and Japan. In other words, 70 billion digital objects will be produced between now and 2030, objects that will consume energy to function but also to be manufactured. Finally, we must favour fixed uses over mobile uses. If you watch Netflix, do it from home with your fibre-optic connection rather than 5G in the metro. Better still, go spend an hour in the forest instead of watching Netflix for hours!

Digital resources should now be considered as scarce resources, which they have not been for a long time. Before, when computing power was limited, software was written carefully to limit the need for computing. Let’s rediscover this sobriety.