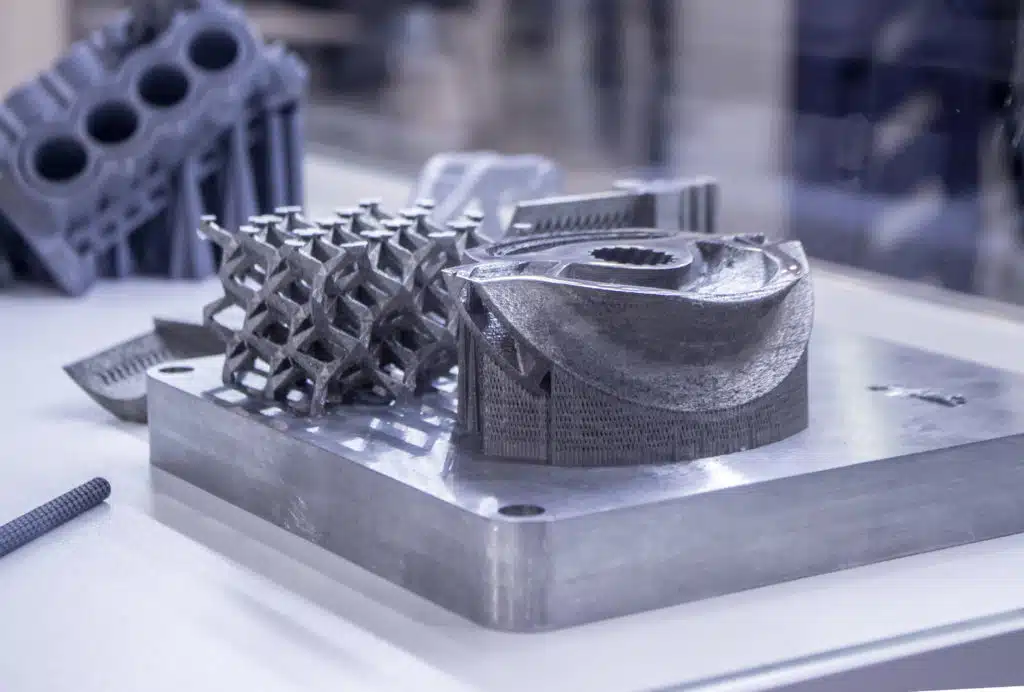

According to Paolo Minetola, associate professor of manufacturing technologies at the École polytechnique de Turin, “additive manufacturing is a green technology.”

“Each object is only made when needed so production uses the minimum amount of material and does not require moulds or specific tools,” he says. “Moreover, 3D printing extends the lifespan of objects provided that they are designed correctly. We can manufacture complex shapes, which are impossible to make with conventional technologies, and with enhanced properties such as lightweight or better heat exchange.”

Economic benefits

Indeed, polymer 3D printing produces very little loss or waste and, consequently, it saves the energy usually required for storage and processing. Furthermore, the parts are often designed to be more lightweight (hollow but resistant). Their use can reduce overall carbon footprint; for instance, in every sector the production of these new structures reduces manufacturing times and costs, but also energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions.

In addition, it is possible to manufacture parts on demand, thus avoiding overproduction and waste of resources. Sharing digital modelling files for specific parts with relocated factories is a great opportunity: the pollution generated by packaging and transportation of equipment can easily be avoided. One can imagine, for example, that in the near future, each aircraft manufacturer will have 3D printers to hand that allow them to rapidly produce spare parts without transportation.

Nevertheless, things are a little more complicated than that. The impacts of this new technology are not easy to assess, especially since 3D printing includes several techniques and uses a range of different materials. Comparison with traditional manufacturing is not always possible and studies on this subject are still rare, especially with regards to the energy consumption of the entire life cycle from beginning to end.

Toxic technology?

Some studies are beginning to sound the alarm on the health risks linked to 3D printing, too. Gas and particles emitted by printing materials that are subjected to high temperatures can become toxic for eyes and skin or affect the respiratory system. These risks are known in the fields of industry and research and, as such, operators wear protectives masks, suits and respirators, and have regular medical check-ups. However, these health hazards are less well known in non-professional environments, especially those of private users. What is more, universally recognised specific ISO standards do not exist yet.

Fabien Szmytka, professor and lecturer at the ENSTA Paris (IP Paris) works with plastic and metallic materials. He points out the fact that these processes can be used in simple environments. “The metallic powders that we use are very fine so we must follow strict protocols to avoid any risk of environmental contamination and hazards for users. Moreover, the output of machines is low, and we lose a lot of raw material.”

“For polymers, we are conducting research with chemists from the CNRS, to develop recycled or bio-sourced polymers,” explains Fabien Szmytka. “For instance, we try to combine them with flax fibres because the composition of commercial polymers and liquid resins is unknown due to industrial secrecy.”

A flawed end of life

Another problem arises when 3D objects reach the end of their lives. So far, there seem to be a lack of plans to collect, store and recycle these new materials of ‘unknown’ composition.

In the medical world, recycling of prosthetics and implants is complicated, mainly due to sanitary and operational reasons. “It is not possible to reuse them because they are often custom-made objects which would not be adapted to other patients. Either way, they would likely be damaged by conventional sterilisation techniques at high temperatures,” explains Bernardo Innocenti, professor in biomechanics at École polytechnique of the Université Libre de Bruxelles.

“For all these reasons, the use of recycled material to manufacture implants is not possible for now. And the patient is entitled to receive the best possible equipment.”

To conclude, there is still a long way to go before we succeed in developing a completely ‘green’ form of additive manufacturing. Nevertheless, we can already bear witness to its huge advantages compared to subtractive manufacturing [cutting a shape out of a piece of material]. Many designers are actively working to anticipate the entire life cycle of new products, in the interest of a circular economy. Additive manufacturing will more likely reinforce conventional technologies by adding its qualities, provided that manufacturers implement new business models, especially with the support of national policies.