With an annual turnover of around €300bn1, the construction and public works sector accounts for 40% of annual waste production in France2. These wasted materials can still often be technically used but they can be costly to dispose of, have sometimes gone “out of fashion” or no longer comply with modern construction standards. This same sector also accounts for approximately 30% of greenhouse gas emissions3, mainly from two sources: the energy consumed for comfort of use (heating, air conditioning, artificial lighting, mechanical ventilation and hot water) and the energy required for extracting the construction materials, transforming them into products, transporting them and finally treating them at the end of their useful life.

The first life cycle analyses carried out by construction professionals have shown that the carbon impact of materials over an entire life cycle is 50% for a new building and 30% for a refurbished one4. Roughly speaking, half of the carbon impact of a building is paid for monthly by its energy bill, and the other half (“invisible” to the inhabitant), lies in the products and materials used to construct the building.

Possible solutions

Solutions for limiting the carbon impact of energy consumption are now well known and are gradually being put in place. They include: limiting energy needs through bioclimatic architecture and a thermally efficient construction; good product consumption management; and using low-carbon energy production (heat pumps, wood-fired boilers, thermal and photovoltaic solar panels and low-carbon urban heating networks).

Such decarbonisation solutions are less common when it comes to materials, but if we take a closer look, they already existed in the past: bio-sourced materials (structures made of wood or insulation made of vegetable or animal wool) and recycled or reused materials (that do not require an unreasonable amount of energy to recycle).

Mobius reuses

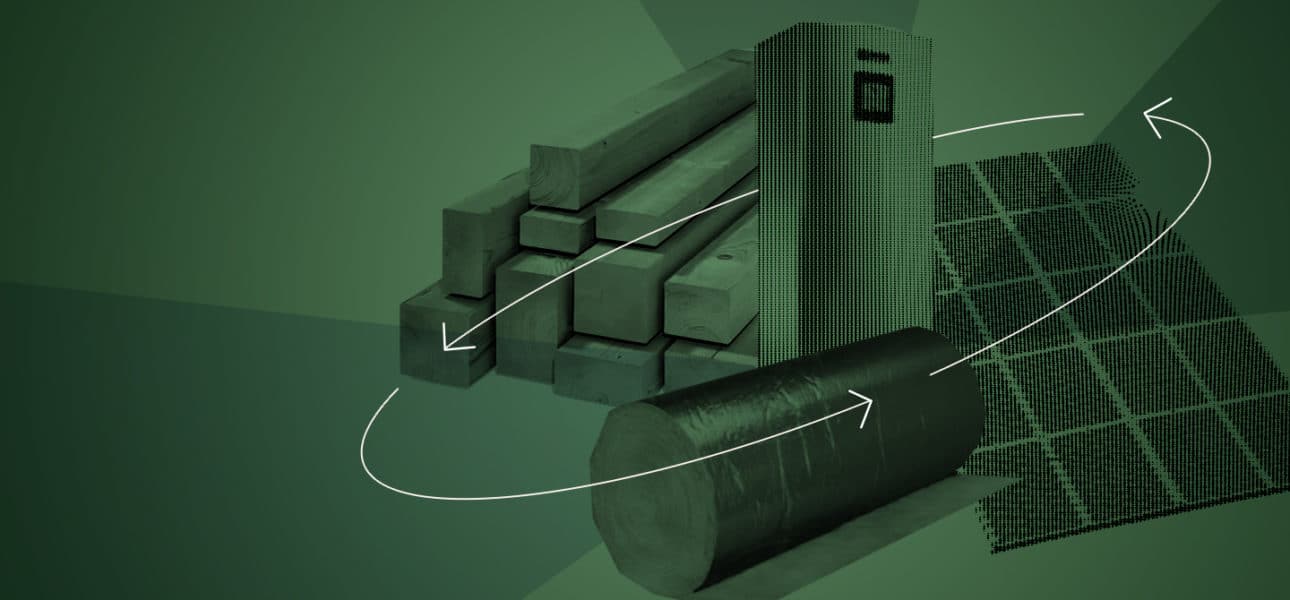

Mobius strives to develop re-employment (a door becomes a door again), reuse (a door becomes a table5) and recycling (a door is shredded and then used as chipboard or burnt for energy).

Our approach first involves diagnosing buildings to define the quantity, quality, ease of removal and carbon impact of each of the products and materials used in their construction. This step is followed by the development of a “master plan”, which involves either material conservation, donation or sale. If the materials cannot be kept, because, for example, they are deemed too old, they can be donated to associations or building companies, for example, who could then transfer the materials to a building site and/or reuse them for their own needs, so dispensing with the need to purchase new materials and avoiding the associated carbon emissions. The waste therefore becomes a valuable commodity because it is no longer considered as waste but as a resource.

These materials can also be recovered by a conventional waste-treatment or demolition company, but using processes that allow them to be reused, packaged and transported. This implies creating and managing storage on site, which is often limited in terms of the space available, so that these elements can be directly recuperated or sold. The percentage of sales is currently relatively low, however, and the main markets are generators, wooden frames and radiators.

In contrast, we propose integrating materials originating from reuse into new or rehabilitated buildings. This approach involves carrying out an architectural and technical feasibility study, from the design phase onwards, to evaluate whether these materials are better in terms of environmental impact than completely new materials.

It is then a matter of looking for future demolition sites from which to recover potential materials for reuse and then recondition them before sending them to a new site. This approach has been developed, for example, in the ZAC Saint-Vincent-de-Paul in the 14th arrondissement of Paris, where more than 60 000 m²6 of buildings have recently been demolished.

Mobius re-industrialises

The main problem with integrating materials coming from reuse is the lack of treatment channels: if you want to install 1,000 reconditioned radiators in one operation in 12 months, for example, it is not easy to find a company big enough to do this. Indeed, reuse is a new domain and requires a certain amount of expertise – for example: identifying demolition sites; recovering the materials; transporting them from a recovery site to a reconditioning site; and then reconditioning these elements and sending them to a new, installation, site.

This is the challenge we have taken on by developing reused subflooring, which comes from demolition sites throughout France and which is then sent to our Rosny-sous-Bois factory, where, after being brushed, sanded and re-graded, will be reused in office buildings, mainly in the Paris region. The result is a 75% carbon saving compared to using a new product, and more than 2 400 tonnes of waste avoided. The return is low, however, because a product made by transforming or assembling existing materials is still cheaper. Reuse is the opposite: you have to pay people to recover, treat, transport and repackage the waste.

Towards a circular economy?

The reuse of construction materials is good for the environment, but, at present, it remains more expensive than using new materials. It is therefore difficult to implement without a particular willingness on the part of construction companies/builders. That said, from next year the construction sector will be subject to regulations requiring the limitation of carbon emissions7. The question will then be: is it better to build with wood, stone, recycled or reused materials?

Finally, as we have seen in recent months, the prices of raw materials can fluctuate sharply and delivery times can become longer. For example, the price of wood and metal has been particularly affected, leading to both additional costs and a slow-down in construction or even factory closures. The advantage of reuse is that it does not depend on these markets and prices can therefore remain stable over time.