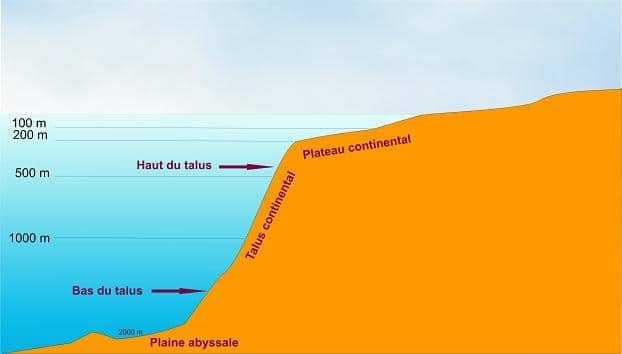

The term “deep sea” brings to mind the adventures of Captain Nemo aboard Jules Verne’s Nautilus… Since then, we have learned a little more about these environments – imagine vast expanses that represent 56% of the total surface of the ocean. For scientists, the deep sea generally begins at a depth of more than 2,000 metres. But the geopolitical definition is different in that the deep sea begins at the end of the continental shelf – closer to the continents – at depths of over 200 metres. For the rest of the article, we will refer to the latter definition.

Dark blue water

If you look at a satellite view of the Earth, you can identify the deep sea at first glance. It is the dark blue water because, at these depths, light does not penetrate. However, there are many animal species that reside there, even if they are few in number. If you were to take a trip on the Nautilus, you would see large, flat, monotonous areas – the abyssal plains – interspersed with numerous landforms: seamounts, sometimes active volcanoes 1 and ocean trenches. Flying over the ridges, you would see huge mountain ranges in the centre of the oceans, which together total more than 60,000 km. That’s equivalent to 1.5 times around the Earth!

“We know the surface of the Moon better than the bottom of our oceans!” Florian Besson reveals. “The best bathymetric map [aka. topography of the seabed] in existence worldwide has a resolution of about 500 metres, compared with 1.5 metres on the Moon.” However, almost 20% of the deep sea has been mapped more accurately by ships equipped with depth probes. Through the Seabed2030 project, the United Nations aims to map the entire seabed at high resolution by 2030.

One of the particularities of the deep seabed is its political situation: only a small part of it lies within the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ). In this case, they come under national jurisdiction, particularly for the exploitation of the minerals they contain. “In France, the mining code governs the exploration and exploitation of resources on land but also applies at sea,” explains Florian Besson. Since it was last updated in 2021, it contains stricter environmental requirements. But most of the deep sea is located outside the EEZ, in international waters. It is then the International Seabed Authority (ISA) that legislates. It was created in 1994 following the entry into force of the 3rd United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). The IAMF issues exploration and exploitation contracts and ensures their control. Today, 31 contracts of exploration with a duration of 15 years have already been granted to 22 entities.

Lacks regulation

No framework has yet been defined for mining in international waters. “The current challenge is to define regulations: it must guarantee very high environmental standards and a fair distribution of benefits among the UNCLOS signatory countries, as international waters are defined as the ‘common heritage of mankind’,” says Florian Besson. “Most mineral resources are located in international waters, and some states, such as the island of Nauru, are putting pressure on the IAMF to define an international mining code by July 2023 2.” In parallel, a treaty to protect the high seas is being discussed under the auspices of the United Nations (UN). Negotiations have been stalled since 2018, and this treaty could, among other things, allow the creation of marine protected areas on the high seas and protect vulnerable ecosystems often associated with marine mineral resources.

These negotiations reveal the interest of states in the deep sea. “Interest in the deep sea is not new: numerous oceanographic missions took place in the 1970s and 1980s, enabling knowledge of certain mineral resources to be increased,” adds Florian Besson. “But in recent years, we have seen a strong revival of interest internationally: some deep-sea metals are of strategic interest for new technologies and green energy.” In France, a national strategy for deep-sea exploration and mining was initiated in 2015 and approved at the Inter-ministerial Committee for the Sea in January 2021 3. The first concrete expression of this strategy is the France 2030 national investment plan presented at the end of 2021, which provides for a “Deep Seabed” objective with a budget of 300 million euros. 300 million. It is intended for exploration to gain a better understanding of these environments 4, the roadmap for which was recently adopted.

High potential

No exploitation contracts have been issued by the IAMF in international waters, but two exploitation permits exist in the EEZs. These are the Atlantis II Deep project in the Red Sea and Nautilus Minerals’ Solwara 1 project in Papua New Guinea. “Neither of them has been successful and probably never will be,” says Florian Besson. “The Red Sea project has been blocked since 2013 by a contractual disagreement between two companies. In Papua New Guinea, the new entity that bought Nautilus Minerals following its liquidation in 2019 now holds the licence, but its activities are rather opaque.”

Apart from the potential economic benefits, the deep seabed crystallises many issues. A report by the Academies of Science and Technology 5 considers that they “offer the opportunity to combine scientific research, technological progress, economic development, security for certain metals and participation in the collective implementation of sustainable management of this new space.” This goes even further than mineral resources: France, for example, recently adopted a military strategy to control the seabed 6, in particular to protect the many undersea communication cables that litter the seabed, as well as the resources and biodiversity.

In this context, research has an important role to play. Knowledge of the consequences of potential deep-sea mining is very limited: in France, there is only one scientific assessment of environmental impacts 7. The scientific community is increasingly looking into this subject, in particular to ensure environmental monitoring during the testing of exploitation prototypes. An analysis of the number of scientific publications dedicated to oceanographic sciences 8 also reveals a significant dynamic. The number of scientific publications is accelerating, particularly thanks to the contributions of China, Japan, and the Republic of Korea. Jules Verne did not think he was anticipating the future so well with his Nautilus …