Is there anything new about ‘surrogate’ warfare?

Andreas Krieg. Surrogate warfare is a conventional concept, used for instance by the US in the late 70s when they trained, funded and equipped the Mujahideen against the Russians. A classic example is the beginning of the British Empire. Britain was able to rule India with just 10,000 British people, and they did this by building up local surrogates that did their fighting locally. With the East India Company, a company was delegated the power to administer a territory and use mercenaries to protect their properties.

However, the global context has changed in terms of how and when we use surrogates. The main factor is an aversion for kinetic operations: not only in the West, but in Russia, China and other countries, today’s decision makers don’t want to launch major combat operations. The UN system works in such robust ways that conventional state on state war is now frowned upon.

Less conventional wars don’t mean no conflict.

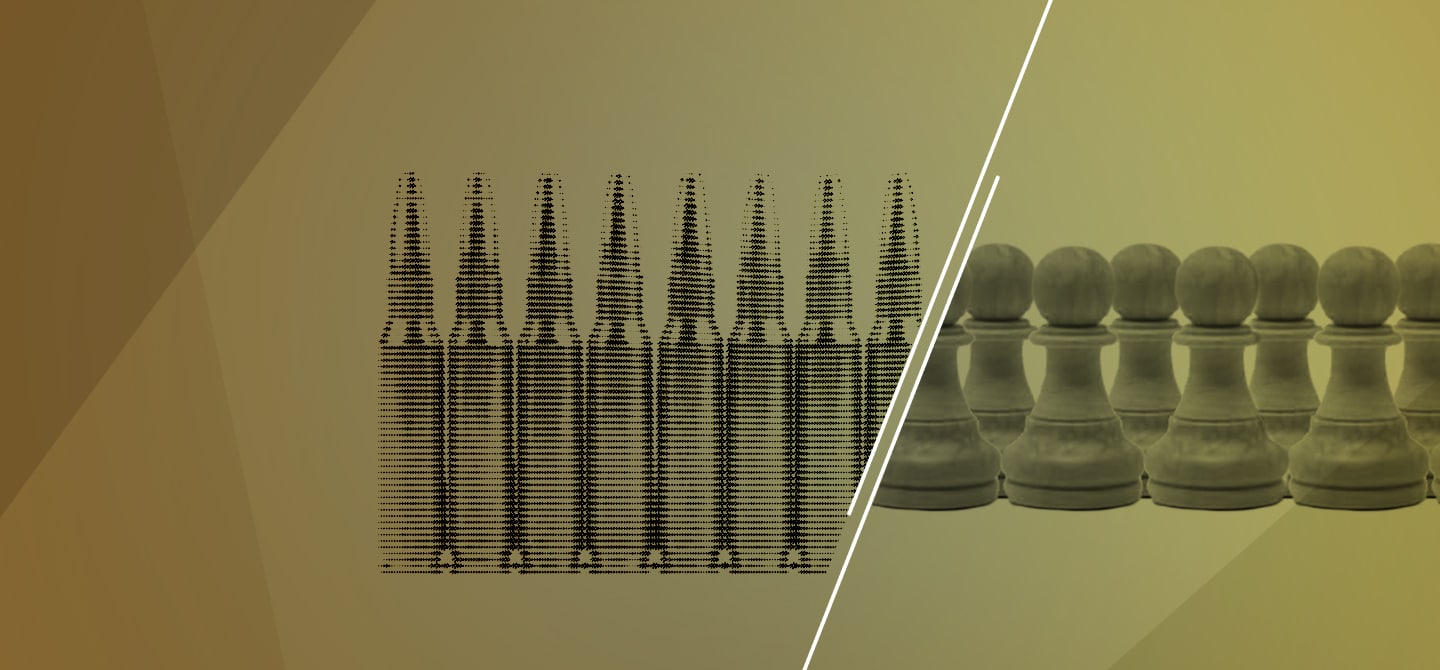

But less conventional wars don’t mean no conflict. With increasing competition between great powers, as well as the existence of unstable zones where conflicting interests are at stake, we live in a state of semi-permanent crisis that can spill into a major conflict. The strategy then is to undermine your opponent without having to cross the threshold into a proper war. That’s where surrogates come in.

Are they capable of achieving the same objectives as conventional armies?

The strategic end of what states are trying to achieve is no longer hold and build, as in the 20th century, where we were trying to push out an enemy, clear a territory and rebuild. The goal now is just to disrupt our adversaries and increase our influence. Surrogacy has very limited relevance for power itself, but it’s a game changer when you want to achieve influence. Influence is built through networks and network building implies delegating to different actors.

Just as it doesn’t provide absolute control, surrogate warfare cannot achieve an absolute victory. But have we ever been able to achieve it? The answer is probably no, though we used to have fairly robust strategic objectives in the 20th century, when we engaged in war.

When we engage in surrogate warfare, we don’t have such objectives. The political reasons for going to war are never clear. We end up being committed in conflict for an indefinite period in locations far removed from our own Metropolitan homeland, which makes it very difficult to sell this war to the media and the public. But we want to remain engaged, and this is what surrogacy allows us to do.

We can remain engaged in conflicts that are not vital for our national interests, with very little democratic oversight and accountability, and with plausible deniability.

What you create through surrogates is complex: it’s an assemblage bringing together state actors, non-state actors and technology, a network that is difficult to unravel. Everyone has a degree of plausible deniability. This discretion allows to do things discreetly without parliamentary oversight, without checks and balances, and it allows what I call “cabinet warfare,” just as in the 18th century when Princes fought wars as they individually saw fit. In the 20th century, with wars involving not only public funding but also citizen’s lives, this kind of warfare was naturally limited. With surrogates the acceptability equation is quite different.

What you said seems even more relevant with non-human proxies.

Indeed. Surrogates cover a broad spectrum and technologies are a very important part of it since they are also a force multiplier to the military. Drones have been used both for their efficiency and to avoid using men and women on the ground – nothing new in the kinetic realm, it’s an old trend. What is fundamentally new is happening in the cyber information domain.

Information wars are using surrogate actors to undermine consensus building. They use the information space to influence not just individuals but large communities, mobilising them to do something that they otherwise wouldn’t do. It’s warfare by other means, just as Clausewitz said warfare was politics by other means. It’s fundamentally changing how warfare operates because it is again below the threshold of war for a strategic political end. It is almost undetectable and definitely not illegal.

Information wars use surrogate actors to undermine consensus by using information to influence not just individuals but large communities.

We have evidence for Russian meddling in the UK, France, Germany, and the US. Targeting discourse in a democracy means that you mobilise civil society to have an impact on policymaking. It is also about changing policy relevant discourse around people who make policy. Everyone has Russia in mind, but the United Arab Emirates are an important case study, because, especially in France, they have been influential on changing discourse on issues relative to Islam or the Arab world. By influencing academics or journalists, you create a whole array and an army of surrogates. The Russians have been weaponising narratives for the two decades, first to defend themselves, and now offensively to undermine the social political consensus in our countries through polarising debates.

The input might come from Russia, but the proliferation of conspiracy theories happens thanks to domestic citizens, “coincidental surrogates” who are not direct agents of the Russians. This is the power of networks. They will spin ideas, disinformation, fake news, and weaponised narratives.

Warfare is essentially changing wills, Clausewitz said. Subversion in the information space allows us to do exactly that without ever having to fight. That doesn’t mean it doesn’t become violent, as we’ve seen the United States this year with the infiltration of weaponised narratives in the public discourse. The outcome was violent, albeit not “kinetic” in the conventional sense.

Beyond this version of subversion, how is surrogate warfare expected to evolve in the future?

What happens next is about artificial intelligence. It creates a means to completely delegate decision-making and remove yourself from the process. You’re not supplementing the human brain. You’re substituting it.

This is already happening on the operational level: AI is part of the robotics in the kinetic machines that are built today. In China, a lot of research is done to remove the human from the loop. 15 years ago, the US was very firm: the human should always remain in the loop. The Chinese think otherwise, and now the American are saying that we too need to do more research into using AI and building systems where the human is no longer in the loop. What we see here is an erosion of the human component of warfare. Technology is taking the lead.

That sort of relationship is difficult to accept: you want the patron to control the surrogate. When it comes to artificial intelligence, the human is no longer able to control it. We’re changing all the parameters of surrogacy, because in a patron and surrogate relationships, the patron always has a degree of control. Shall we eventually have to create machines to control the machines? This is a slippery slope that we’re going down.