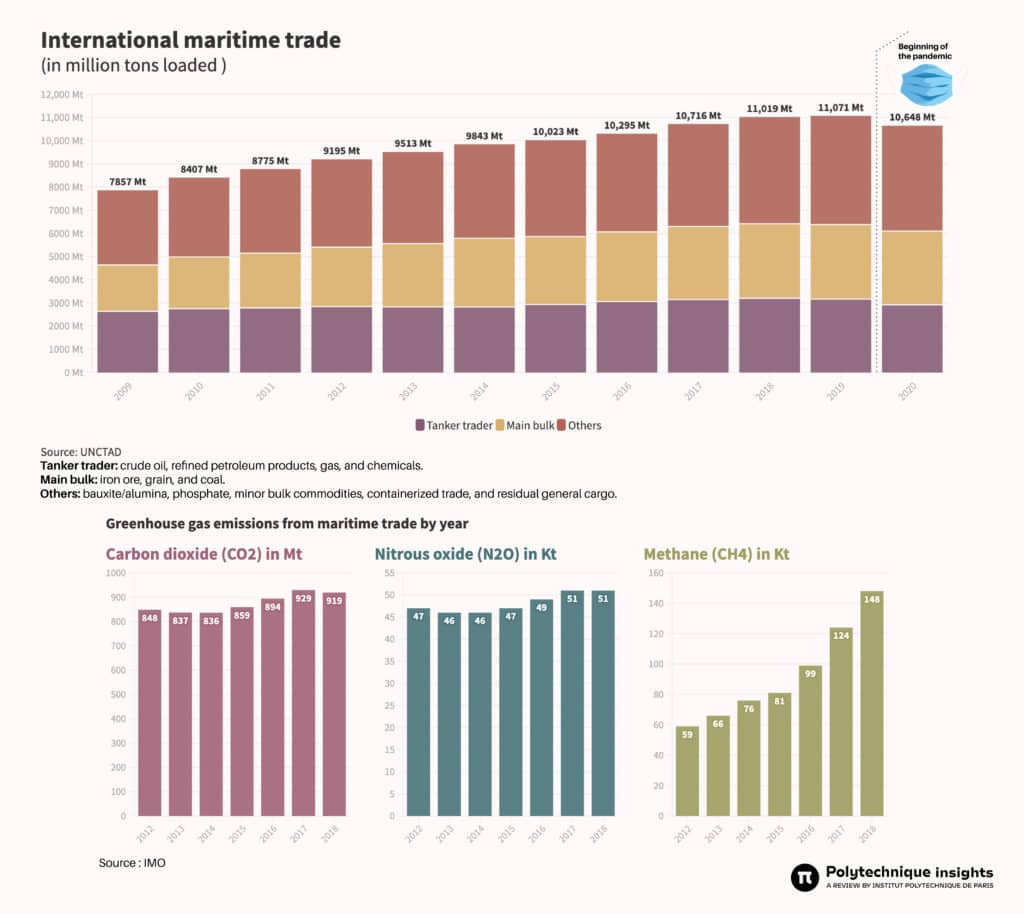

In 2018, the shipping sector emitted just over one billion tonnes of CO2 into the atmosphere. This represents 2.89% of global anthropogenic CO2 emissions according to the latest global estimate 1. The main contributor to these climate change emissions? Sea freight. It includes the transport of vehicles, passengers or refrigerated goods, but also sectors of activity that weigh more heavily in the carbon footprint by their number of units and the tonnages involved. Container ships, bulk carriers, oil tankers, chemical tankers, cargo ships and gas tankers account for 86.5% of emissions from international maritime transport. “It should be noted that these figures only represent fuel consumption: they do not take into account all emissions, from the manufacture of ships to the post-transportation of goods,” emphasises Éric Foulquier.

The total greenhouse gases (GHG) emitted by maritime transport – CO2, methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O) – amounted to 1,076 million tonnes in 2018, up by almost 10% compared to 2012. The sector’s carbon footprint is predominantly due to CO2, but in recent years some changes have been observed. Because of a decrease in sulphur content limit in fuels, the proportion of heavy fuel oil consumed is falling (-7% between 2012 and 2018), to the benefit of maritime diesel (+6%) and liquefied natural gas (+0.9%). As a result, CO2 emissions are stabilising while CH4 emissions are increasing (see article 2).

Maritime freight, a busy circuit

Maritime freight plays a major role in world trade and economic development. In 2020, the world’s maritime fleet numbered 99,800 ships, including almost 54,000 merchant ships 2 carrying more than 80% – or even more for the most developed countries – of the goods traded around the world 3. “As of 2015, at least 10 billion tonnes of goods are loaded annually in the world’s ports. It is interesting to note that since 2013, countries considered to be developing have been unloading more than they load,” adds Éric Foulquier. “This undoubtedly corresponds to the emergence of a middle class in these countries, in line with the development trajectory they are on.”

In terms of its climate footprint, is maritime freight an efficient mode of transport? A container ship emits 3 grams of CO2 equivalent per tonne per kilometre, compared to 80 for a truck or 437 for a cargo plane 4. “Comparing modes of transport according to this indicator minimises the impact of maritime freight, but it is more realistic to express it in absolute terms,” says Éric Foulquier. “It makes no sense to compare these modes of transport: the sectors are different, and they often complement each other in terms of global economic circulation.”

Particles also emitted into the atmosphere

Since 2005, when the MARPOL Convention was adopted, sulphur oxide emissions from ships have been regulated and the thresholds regularly reviewed (fuels are now limited to 0.5% sulphur content). Four Emission Control Areas (ECAs) – sea areas where the limit is raised to 0.1% sulphur content – have been established. Despite these measures, the IMO notes [1] an increase in emissions of sulphur oxides and atmospheric particles. This pollution has harmful effects on human health, causing lung disease, but also on the environment by causing acid rain.

Emissions can be reduced

So how can we decarbonise this vital sector? The carbon intensity of ships – the amount of CO2 emitted per tonne of cargo per kilometre – has already been reduced by 20–30% between 2008 and 2019 5. This has been achieved through the replacement of older ships, the purchase of larger ships, but also through technical and operational measures. Since the financial crisis of 2008, a majority of shipowners have adopted slow steaming, reducing their speed by 20–30% between 2008 and 2015 6. A stable figure since then. While it was not considered at all before 2009, energy consumption is now the second environmental priority of the European Sea Ports Organisation 7, behind air quality. It is also a financial concern: if you double the speed of a ship, its fuel consumption quadruples.

However, these efforts are being undermined by the increase in freight flows: GHG emissions from maritime transport have increased by 30% since 1990 8. The capacity of maritime freight has increased from 1 to 2 billion between 2006 and today 9 and is expected to reach 3 billion by 2030 10. “Maritime transport is only one response to the needs of our society, we must act on the flows”, states Éric Foulquier. By 2050, the International Energy Agency estimates that CO2 emissions linked to freight should increase by 135% compared to 2018 levels 11, while the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) estimates this at +250% by 2035. “The massification in which we find ourselves must be profoundly reconsidered in favour of the demassification of the commercial world, which is necessary if we are to implement a transition,” the researcher argues. It implies shorter circuits, the mobilisation of small ports organised around medium-sized urban centres.

Targets have been set

Driven by the global objectives of carbon neutrality, the regulatory context is also changing. By 2050, the IMO is aiming for a 50% reduction in the sector’s GHG emissions compared to 2008. The European Union has a much stronger commitment to achieving carbon neutrality by 2050, after an initial 50% reduction in emissions by 2040 compared to 1990. In 2020, the European Parliament voted to include maritime transport in the EU’s emissions trading scheme. The measure should be effective by the end of 2022. However, the International Monetary Fund estimates that “a tax of US$75/tonne by 2030 would promote a reduction of only 15% of current emissions.”

The shipping sector can choose to rely on many levers to reduce its CO2 emissions. Operational measures – speed reduction in the first instance, but also weather routing or overall energy efficiency measures – have the potential to reduce GHG emissions by up to a third [4]. Finally, a significant potential for decarbonisation lies in technological solutions: modification of ship design, improvement of machinery, but also the integration of renewable energies (alternative fuels or propulsion) into the energy mix.