Decarbonising the energy and electricity mix has become a priority to meet international climate objectives. Since 2010, investment in renewable energy has greatly increased (~$3,800bn)1. In 2020 alone, more than $500bn was invested across all kinds of low carbon technologies (power generation, hydrogen, storage, CO2 capture and storage, and electric vehicles) – more than investments into hydrocarbon exploration and production.

While this shift is enabling countries to be partially released from the economic and geopolitical stakes related to energy security, it could cause other geopolitical issues to become more complex, with new dependencies emerging. The energy transition is influencing the overall dynamic felt on raw materials markets, as it is clear that demand for certain materials such as cobalt, lithium, rare earth elements and copper will accelerate, since they are needed for low carbon technologies.

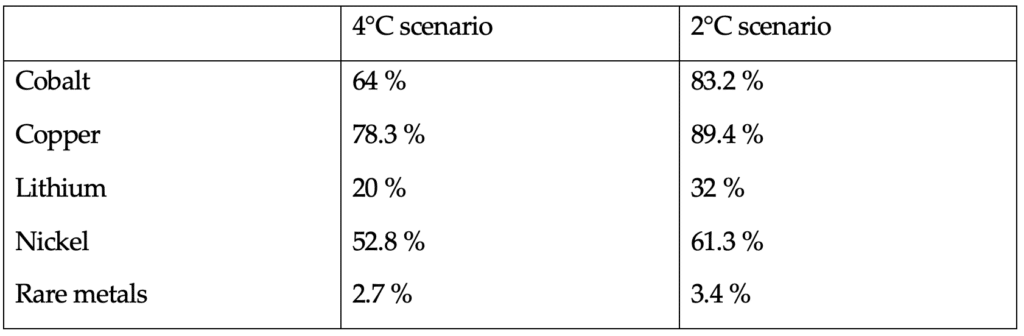

In our scenarios (cf. table 1), cobalt and copper will be the most restricted metals in the energy transition dynamic, as more than 80% of currently known resources will have been consumed by 2050. Nickel and lithium, mostly used in the battery sector, will also be running low in the future, whereas rare earth elements seem to be the least geologically limited.

Alongside this geological risk, the energy transition may also strengthen the position of players (countries or companies) involved in these metals’ various value chains. On this note, the cobalt market is remarkable, as it is dominated by one main player at either end of the value chain – the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), which provides 70% of production, and China, which undertakes more than 50% of processing. The cobalt market is symptomatic of other raw materials markets, subject to serious supply risks due to safety, environmental and social problems in the DRC (such as pollution, large number of illegal mines, and child labour), but also to China’s strengthened role in the area.

On the lithium market, issues are geo-economic in nature. On the one hand, there no longer seems to be a risk of the main producing countries (Australia, Chile, and Argentina) cartelising the market, à la Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), or countries in the Lithium Triangle (Argentina, Chile, and Bolivia) forming a coalition, as national strategies have veered apart. The biggest problem is found on the commercial side of things. At present, the market is dominated by five companies – two American (Albermarle and Livent), one Chilean (SQM), and two Chinese (Tianqi Lithium and Ganfeng). They alone hold more than 80% of market share, with nearly 66% for Albermale, Tianqi and SQM. The Chinese companies’ rise to power since the early 2010s shows the extent to which lithium is considered a strategic material for China. And these companies’ current policy involves purchasing concessions or companies from producing countries. They are seeking to consolidate their access to resources, in order to control the entire lithium production sector, from processing to battery manufacturing.

Rare earth elements, considered as relatively unproblematic from a geological point of view, have been nicknamed the “vitamins of modern society” due to their various properties (electrical conductors, thermal stability). They are currently used in many cutting-edge sectors, such as renewable energy and the military. At present, China represents approximately 62% of global production, followed by the United States (12%) and Myanmar (10%). China was able to quickly establish itself on the market, thanks to extremely strong cost competitiveness, and has invested over time in all parts of the value chain. The rare earth elements market is undergoing major transformations at the moment. While China is already the biggest producer and consumer worldwide, its exports could go down in coming years to satisfy domestic demand. As is the case for other raw materials markets, Beijing is trying to make overseas investments, but is coming up against other countries in serious geo-economic competition.

New market powers could arise in the coming decades for all these raw materials. Some producing countries (Chile, Australia, Argentina, DRC, and Bolivia) have a source of wealth at their fingertips, which could be a major provider of economic development as long as mining revenue is managed efficiently and funnelled back into the local population. Out of all the nations involved, China already has a clear advantage, as its strategy to secure supplies of raw materials (spearheaded by the “New Silk Road” project and direct investments overseas) is making it the key player in all these markets. Strategic raw materials could be the subject of a dispute between China and the United States in years to come2.

The environmental and societal consequences of mining raw materials are also becoming key stakes for domestic politics. It’s very possible that, in the next few years, the chronic instability in some producing countries will intensify. The issue of water and its distribution between citizens and industrial raw materials producers could very well become crucial for internal politics in many countries. This shift could be strengthened by the energy transition and low carbon technologies, which consume large quantities of water, as the main areas that produce strategic materials experience serious water stress3.

The issue of raw materials will dominate the 21st century, as will the complexification and globalisation of economic and geopolitical relations between the various players.